Friday 26 October 2012

The Girl Who's Been There All Along

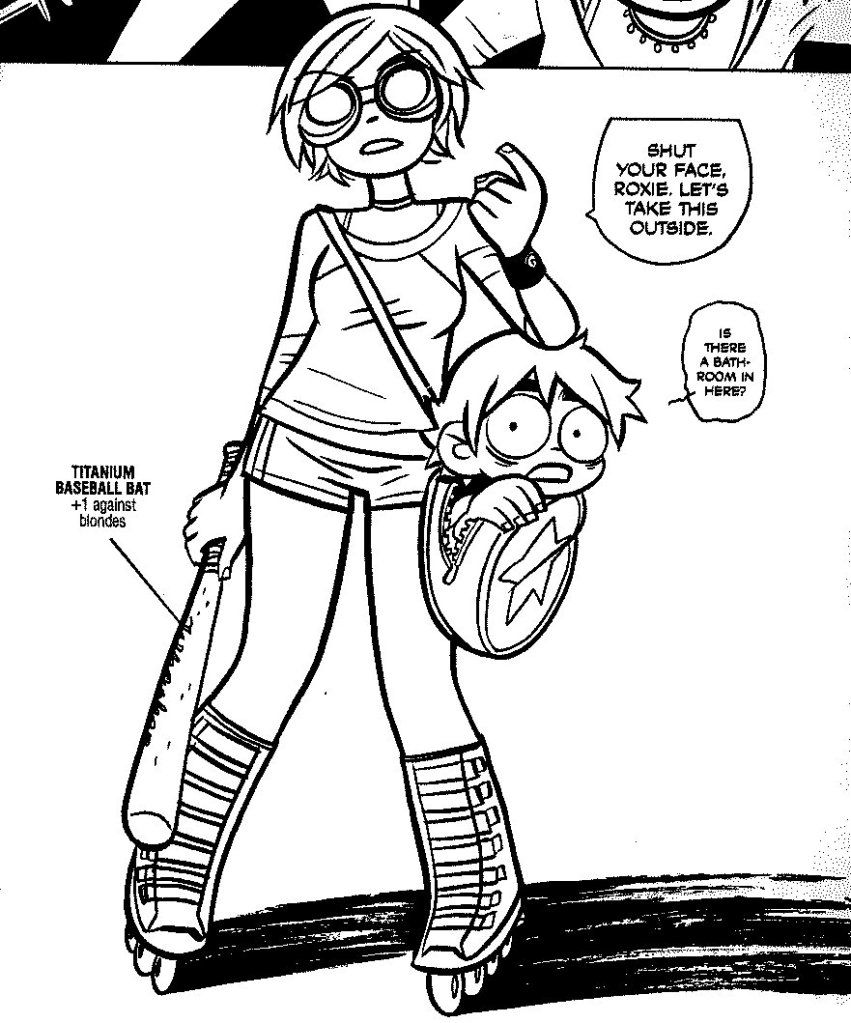

In the marketing for the film, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, Kim Pine is described as “the sarcastic one.” The movie’s two-hour runtime demanded an all-encompassing simplification of the story from which few characters escaped unscathed. The greatest casualty aside from Ramona, Kim retains -- but is also ultimately reduced to -- her quick, acerbic wit. The Kim of the film is not the Kim of the comic, but rather the self that Comic!Kim wishes the world to see.

At first glance, Kim is a simple character: she hates everything. In fact, she is almost relentlessly pessimistic. She never misses a chance to talk about how much Sex Bob-omb sucks. She leaps at every opportunity to criticize Scott. She despises everyone, including her friends.

Except, of course, that she doesn’t. She loves music, evidenced by the flashback in which she pauses in the middle of a back seat session with Scott to get him to listen to the song on the radio. Although she acts like Sex Bob-omb’s rehearsals and gigs are the worst part of her day, she later confesses that they give her life structure and, at the end of the series, we see that she has joined Scott’s new group, Shatterband. Keeping time behind a drum set seems to give her some kind of control, real or imagined, over what is revealed to be a pretty dismal existence.

In a conversation with her boss, Hollie, Kim tells her that she hates her. “You hate everyone, Kim,” Hollie observes, prompting Kim to reply, “You’re one of everyone.” Although this exchange is clearly intended to be funny, there is more than a little truth to the statement, and more than a little justification for Kim’s misanthropy. Most of the people in her life really do suck. While Scott is too busy fighting exes to direct our attention to her, Kim suffers a number of personal blows. She deals with the roommates from Hell (whose antics are briefly chronicled in a separate one-shot entitled, as ironically as humanly possible, “The Wonderful World of Kim Pine”), before moving in with Hollie. Hollie promptly sleeps with Kim’s boyfriend, thereby turning her home -- already the site of the recording that has disrupted the steady rhythm of her life -- into a hostile territory. It’s not difficult to see how Kim could claim to hate everyone.

“Everyone,” however, has some notable exceptions, among them one Ramona Flowers. Ramona and Kim forge a friendship based on their mutual disdain for idiocy as well as a genuine appreciation for each other. They banter easily, but Kim knows when to give Ramona her space. The best example occurs when Kim notices Ramona’s head glowing and decides to gather photographic evidence in order to confront her about it. When Ramona gets defensive, Kim backs off, saying, “If you can’t tell me, you can’t tell me. I won’t be offended.” She tries to make Ramona see that there is a problem, but doesn’t force her to deal with it. In a series with numerous girl vs. girl verbal and physical smackdowns, such a friendship is refreshing. Kim’s ability to handle Ramona also clarifies the nature of her misanthropy: she dislikes people not because she doesn’t understand them, but because she so clearly does, which may be the reason why she always expects them to let her down.

And let her down they do, perhaps no one more than Scott. In the fifth volume, while in the process of kidnapping her, the Katayanagi twins observe that she has “been there all along,” standing beside Scott. While she does insult him, she also encourages him; for every few digs along the lines of “Scott, if your life had a face, I would punch it. I would punch your life in the face,” there’s a “Come ON, Scott! You can do this, you know. You’re not as clueless an idiot as you seem!” Unfortunately, Scott does not offer the same support in return.

The altercation with the Katayanagis is a defining moment for Kim, as she is confronted with the reality of her one-sided relationship with Scott. Still, even when she cannot convince Scott to save her for her own sake, she helps him to defeat the twins by pretending that her inspirational words are Ramona’s. In a way, by manipulating Scott, she saves herself. As Kim departs at the end of the book, Scott apologizes for everything. When Kim dismisses it, telling him it’s not his fault, he shouts, “Sorry about me!” This is the apology that Kim can accept.

Kim’s importance to Scott Pilgrim as a character is reflective of her importance to Scott Pilgrim as a series. If Scott is the lens through which the story is told, and Ramona is its focal point, Kim Pine is the person standing next to you, pointing to the lens and saying, “Trust nothing it shows you.” Throughout the series, Kim serves as a kind of bullshit detector, as she uses her substantial powers of observation to interrogate Scott’s version of events. She questions his decision to date a high schooler, his validity as a hero, and, ultimately, the reliability of his narration. Multiple characters point out the holes in Scott’s recollections, but Kim is the person who breaks him out of his cycle of forgetting and forces him to restore the memory of his mistakes. Her own story literally replaces the one we already read, panels from earlier volumes juxtaposed with new versions in a displacement of fiction by fact. Kim is the person responsible for dismantling Scott’s subjective narrative.

This is why her diminished presence in the film is such a crime. The viewer’s perception is even more closely tied to Scott’s point of view, which is worrying on a metatextual level. In the film, the dominant narrative isn’t questioned, whereas, in the books, the convenient lies Scott tells himself are replaced by the truth as witnessed by those he wronged. The film eliminates so many of the book’s more compelling ideas about the importance of perception in storytelling. For this reason, we would have preferred it if the girl who has “been there all along” had actually been there in her entirety.

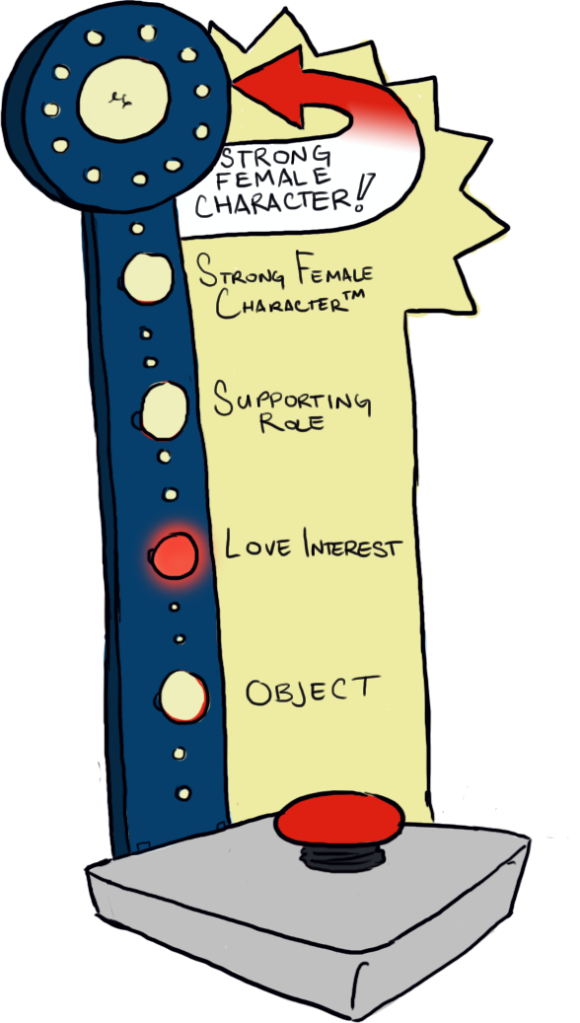

It’s difficult to determine where Kim falls on our scale of character strength. She is a past love interest, as well as a supporting character in every sense of the word. She has her own life, but we are largely denied access to it. The life we do see technically revolves around a man, but she has clearly decided to make a change in that respect. We’re inclined to say that she falls somewhere between the categories of Strong Female Character ™ and Actual Strong Female Character, but we’re certainly open to other interpretations.

Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character ™

Friday 19 October 2012

This One Girl With Hair Like This

RAMONA FLOWERS

AMERICAN NINJA DELIVERY GIRL

AGE UNKNOWN

EVERYTHING UNKNOWN

FUN FACT: UNKNOWN

Ramona Flowers is American. Ramona Flowers is the girl of Scott Pilgrim’s dreams, literally. Ramona Flowers is a mystery, wrapped in an enigma, wrapped in a conundrum, all surrounding a squishy, straightforward centre: a Tootsie Roll Pop of characterization. And if Scott Pilgrim is the lens through which the story is told, Ramona Flowers is its focal point.

When she first enters the story, rollerblading across an arid desert of loneliness, Ramona seems like she will be no more than one more in a long line of Manic Pixie Dream Girl characters. The MPDG is a term coined in 2005 to describe a young, spirited woman who is so high on life that she must drag the male protagonist along for the ride, turning his boring life upside down and giving him the motivation he previously lacked.

Like many a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, Ramona is introduced as the solution to the male protagonist’s dull, static existence. She is quirky, intelligent, and ever-changing. Unlike the typical MPDG, however, Ramona clearly has an existence outside the protagonist’s limited world. Her mysterious allure is less the result of a personality tailored to the needs of the hero than a simple matter of the hero not taking an interest in learning about her. The MPDG trope is brutally taken to account when Scott and Ramona have a discussion about what attracts each of them to the other. Scott claims to like Ramona because she is mysterious, and Ramona quite understandably thinks that that’s not enough and that he should know more about her like, say, her age. When he replies that it’s unknown, as if that’s a valid excuse, she responds by saying that he could just ask. In this moment, Ramona introduces the idea that she is not a mystery forever resisting a solution, but an actual person with whom Scott could interact on a human level.

Because the series is so thoroughly based in Scott’s subjective viewpoint, it makes sense that the reader comes to know Ramona just as Scott does. In the first volume, Ramona is introduced as a prize, and objects have no need of a personality. In order to win her, Scott must defeat her seven evil exes in a series of increasingly difficult boss battles. What is particularly interesting is that Matthew Patel, the first evil ex, emails Scott before Ramona has expressed any interest in him; he begins the path toward winning Ramona even before she has consented to being won.

One of the great accomplishments of the series lies, then, in the paradigm shift from viewing a woman as an object to be won to accepting her as a whole person with agency and subjectivity; this is the development from apparent Manic Pixie Dream Girl to Actual Strong Female Character. Ramona is not perky, upbeat, or fun-loving; rather, she is sarcastic and brutally honest, encouraging Scott to grow up and take responsibility for himself instead of luring him out into the world through the sheer force of her frenetic energy. Despite her use of subspace travel, she is not some sort of otherworldly being. In fact, the text goes to great lengths to point out similarities between Scott and Ramona, from their propensity for cheating to their selfishness to their decision to take wilderness sabbaticals following their break-up. Just as Scott turned to video games to escape from his problems, Ramona, who had intended to work through her own issues, “just ended up sleeping all day, dicking around on the Internet and watching every episode of The X-Files.” In that moment, she may have become the most relatable character in the series.

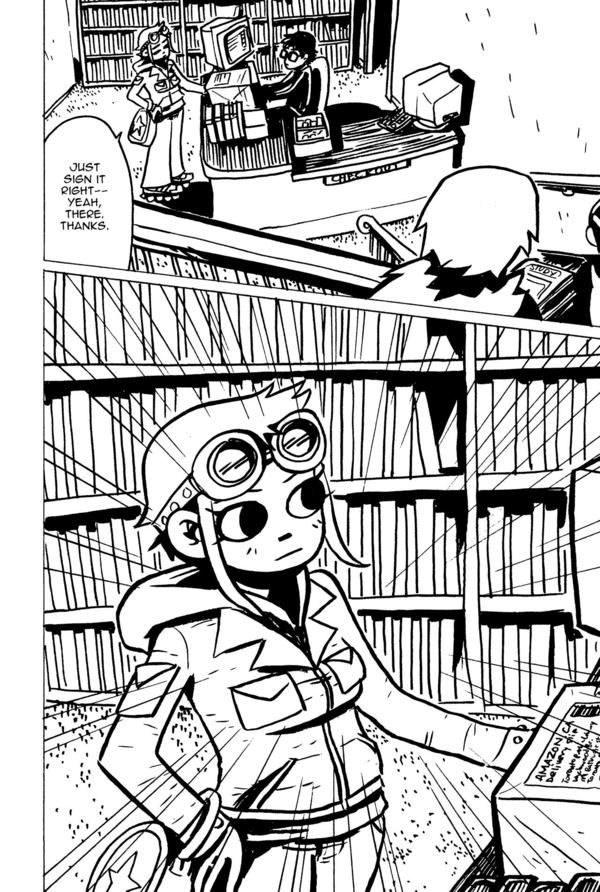

Although she resembles Scott in certain ways, she exists outside of him. Like Princess Kida, it seems like we meet Ramona part way through her own story: a comic already in progress that just happens to crossover with the one that we’re reading. She has an extensive backstory involving her seven evil exes (and at least one non-evil one) delivered in intriguing, if sometimes frustratingly brief, snippets. She also has her own friendship with Kim, based on their mutual hatred of idiocy. By the third volume, Ramona turns the quest narrative on its head by taking her own shot at defeating an evil ex: Scott’s former girlfriend Envy Adams. At this point, Scott temporarily becomes a prize. Ramona further subverts the narrative by fighting Roxie, her fourth ex, in a sense fighting the battle for her self (and shooting for her own hand).

In the fifth volume, Ramona gains some autonomy from Scott’s point of view, achieving a kind of temporary subjectivity. She has a series of introspective moments, the most revealing of which occurs, conveniently, as she tries on clothing while shopping. In the two-page scene, she is clearly dissatisfied with herself; no outfit seems to work, so she tries to adjust her hair, and finally takes refuge in her hood. Throughout the scene, we see both her and her reflection but, while at first we mainly see her, as the scene goes on, we see more and more of the reflection and less and less of the person. The fact that Ramona ultimately decides to hide her hair -- her most distinctive feature -- is telling. Bryan Lee O’Malley has stated on his blog that Ramona changes her hair to try on different identities, depending on the emotional state that she is in. Covering it, then, suggests that she cannot face any version of herself.

This finally changes in the final book. The sixth volume marks the moment when Scott comes into his own as a person aware of other people; accordingly, it also contains Ramona’s crowning moments of character development. After a long absence, Ramona re-enters the story at the end of all things... or, at least, the end of Scott. This entrance directly echoes her first one, but this is definitely not the same Ramona. She observes in a candid moment, “Yes, I’m selfish. I’ve dabbled in being a bitch. But listen... I came back because... because I’m always the one who leaves. I could never say goodbye. I don’t want to be that person anymore. So... I’m sorry, Scott. I came back to say I’m really really sorry.” She does come back for herself, but explicitly in order to make a better version of herself.

In a series that revolves around the battle for Ramona, the best moments occur when she takes an active role in the fight. In this final showdown, we learn that Ramona has made a habit of beating Gideon at his own game. The bizarre glow that allowed her to disappear was originally invented as a form of imprisonment; Gideon states that it “seals you inside your head. Just you and your issues. And once you’re hit, that’s it. No cure. It’s chronic. … But this brilliant self-hater, she found a way to turn it to her advantage...” Ramona transforms these mental shackles into a form of liberation, using the glow as a way to access subspace.

When she is imprisoned in the all too literal -- if technically figurative -- shackles Gideon forces her to wear in her head, Ramona frees herself, telling Gideon, “You know, you’re right. Part of me does still belong to you. But the other parts of me... are finished with you!” A league entirely comprised of versions of Ramona that we have seen throughout the series appears to back her up as she banishes Gideon from her head, forever answering the question, “You and what army?” As if that weren’t enough, she then blocks the blow that would kill Scott using her subspace suitcase, literally and figuratively shedding her baggage. Finally, she gains the Power of Love, just as Scott did in Volume 4, and teams up with him to take down Gideon with simultaneous slices. Ramona is just as much a hero as Scott.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the film version. Changes must be made when adapting six books into one movie, but it’s still unfortunate that Ramona’s characterization loses so much in the translation. Movie Ramona is a far more straightforward Manic Pixie Dream Girl. She goes back to Gideon because she “can’t help [her]self around him.” He has a way of getting into her head, and that way is a microchip, apparently. (Neither its presence nor its shutdown is really explained.) She steals Envy’s shining moment, kicks Gideon in the groin, takes a beating for her troubles, and then spends the final battle looking on as Knives teams up with Scott to beat Gideon. Knives encapsulates all the problems with this version in one line: “You’ve been fighting for her all along.”

The Ramona of the comic fights for herself. There’s a big difference between being a sprite on a screen and the person playing the game, and we’ll always side with the woman holding the controller.

Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character (comic) and Love Interest (film)

Friday 12 October 2012

The Paper Bag Princess

Making

your way through the checkout at the grocery store, it’s almost

impossible to miss the constant coverage of Kate Middleton. Her face is

everywhere, and you could almost be forgiven for thinking that she had

actual political power. The world watched as she married Prince William,

because there is nothing that people -- and especially Americans --

like more than watching a young woman become a princess.

There is ample evidence of this phenomenon. Beyond the tabloid coverage of real British royalty, we are surrounded by fictional princesses at every turn. Disney has made millions of little girls consider “princess” as a valid career option. ABC’s show, Once Upon a Time, features several members of the official Disney Princess line-up, while NBC has included elements of princess stories in the police-procedural-slash-fairy-tale Grimm. The upcoming Maleficent is set to give us a different take on Sleeping Beauty, while this year’s Mirror Mirror and Snow White and the Huntsman have made Snow White relevant again. Even Stephen Sondheim’s musical, Into the Woods, is getting the Hollywood treatment.

The popularity of the princess is not limited to the silver screen. Indeed, if you walk into almost any bookstore, you will find this week’s featured text. The Paper Bag Princess, written by Robert Munsch and illustrated by Michael Martchenko, has sold over three million copies in multiple languages including Arabic, Chinese, and Flemish. The copy Megan picked up when she couldn’t find the one she was raised with is from the seventieth printing. Munsch did his first readings of the story in 1973 and ‘74, and the book was first published in 1980. A twenty-fifth anniversary edition was released in 2005, and it included a behind-the-scenes look at the classic children’s story.

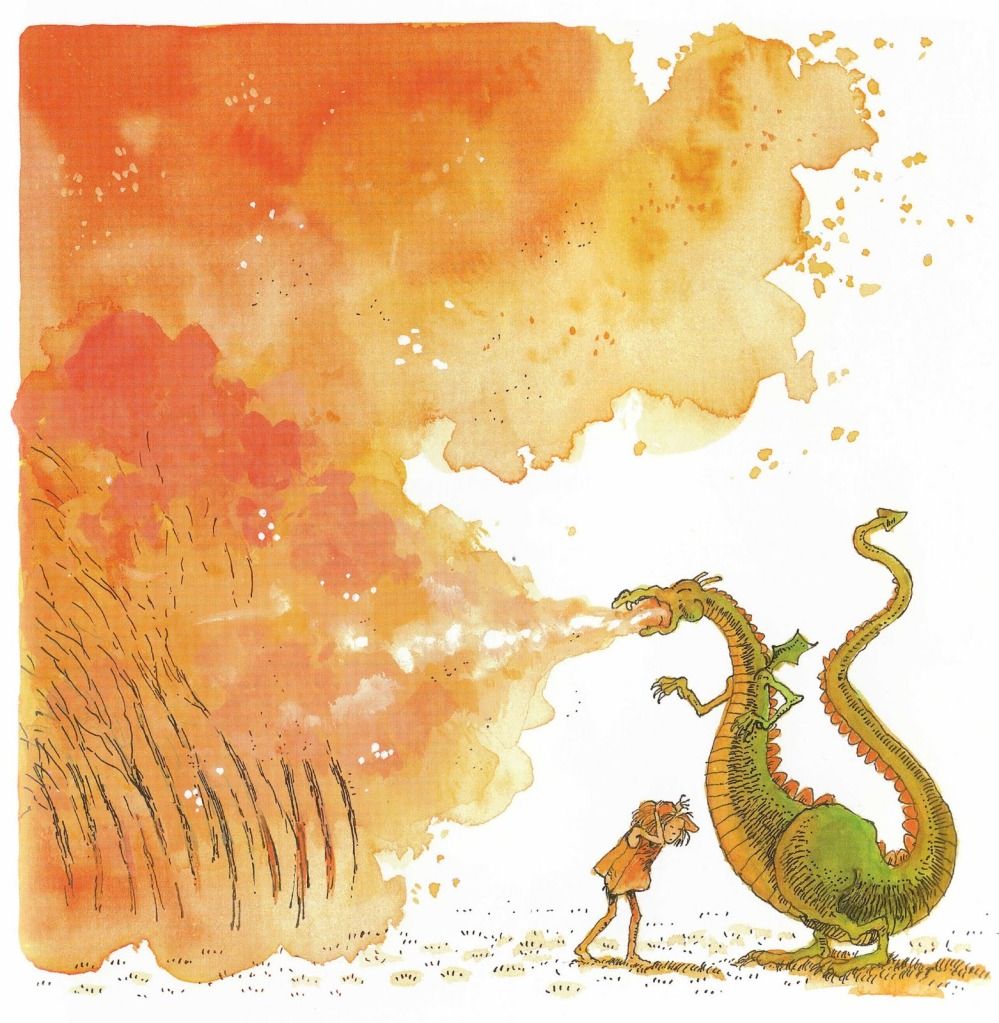

This is another of our foundational texts. At the same time as we were learning that princesses should sing, talk to animals, and be really, really, ridiculously good-looking, we discovered that this wasn’t the only option. The titular character of The Paper Bag Princess is Elizabeth, a girl introduced as just such a character. When we first meet her, she is beautiful, lives in a castle, wears expensive clothing, and is engaged to marry a prince. By the second page, however, she has lost all of this at the hands of a dragon. And she is Not Amused. Faced with her own lack of clothing, she repurposes a paper bag into a dress and goes to save her prince.

This is the first major subversion of princess-based fairy tales: the prince becomes the damsel in distress. Elizabeth not only decides to save the prince, she chooses to do so immediately after losing everything, including the clothes on her back. She displays immense resourcefulness by first making what must be the only flame-retardant paper bag in existence into a new outfit, then proving that it is the only suit of armour that she will need.

Unlike a fairy tale prince, when she finds the dragon, she doesn’t offer to face him in physical combat. Instead, she frames their conflict as a battle of the wits, knowing that she can use the dragon’s strength against him. This is precisely what she does, appealing to his ego and convincing him through a combination of ludicrous dares and flattery to exhaust himself.

Once the dragon’s out cold, she releases Prince Ronald, and here we get yet another subversion, though admittedly not as delightful as the others. If you read “Just Another Princess Movie,” the article we linked to in the New Age of Princessery post, you are familiar with an argument Lili Loofbourow made: that Merida, having displayed her immense athletic ability and winning her own hand, does not receive cheers, only silence and disapproval. A young woman doing what is not socially acceptable is, in many situations, not going to be praised for her achievement.

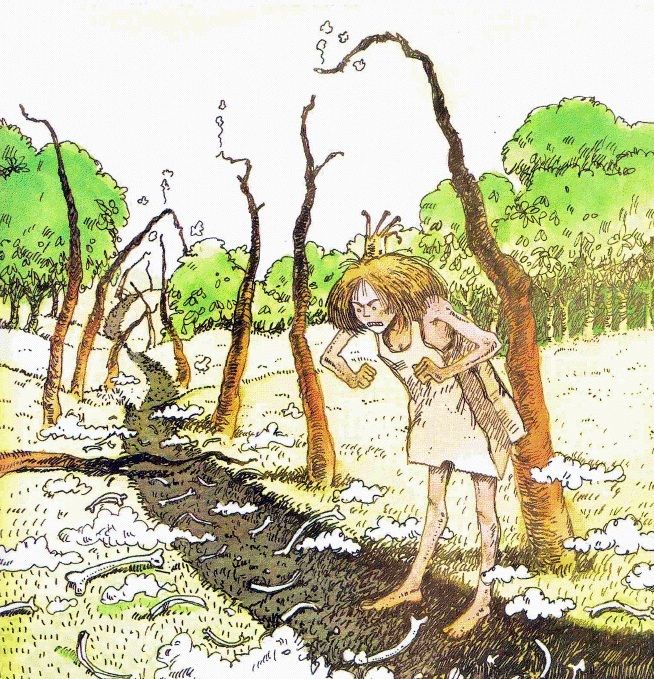

Accordingly, Ronald’s first reaction to being saved is not to thank Elizabeth for risking her own life, but to criticize her appearance. Ronald observes, “Elizabeth, you are a mess! You smell like ashes, your hair is all tangled and you are wearing a dirty old paper bag. Come back when you are dressed like a real princess.” In perhaps the most satisfying reply possible, Elizabeth turns his own words back on him: “your clothes are really pretty and your hair is very neat. You look like a real prince, but you are a bum.” Elizabeth has no time for shallow people who evaluate women based on their physical appearance instead of their actual accomplishments. Ronald is unable to look beyond the dirt to see Elizabeth’s BAMF-ness; Elizabeth, however, has learned to see past appearances to Ronald’s rotten core.

For us, the most satisfying sentence may be the last. Having witnessed a distressing number of Disney princess marriages over a period of a little over a month, we find that there are few sweeter phrases than “They didn’t get married after all.”

Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character

One of the major issues we will be discussing on this blog is adaptation. We are all used to seeing our favourite comics and books become our slightly less beloved movies and television shows. We know that characters we adore in an original text may not even merit mention in its adaptations. In addition, the nuanced characters of the original may be altered to suit the more streamlined aspect of a single episode or film. This doesn’t always work in female characters’ favour.

Between 1991 and ‘92, a series of television adaptations of Munsch and Martchenko’s stories ran on CTV in Canada, and Showtime and Golden Book Video in the United States. Among the tales adapted: The Paper Bag Princess. Among the tales we wish had not been adapted: The Paper Bag Princess.

The first and most fundamental change occurs in the first sentence. Instead of opening with Elizabeth, the episode begins by establishing the fantasy world and, most importantly, the existence of dragons. Elizabeth is an afterthought, in both the story and her own life. We meet her as she is contemplating a romantic day out with Ronald, and, because this is apparently a Disney movie, she sings about him. Normally, we’d only include snippets of the song in order to make our point, but the lyrics really have to be seen in full:

Elizabeth is portrayed as obsessed with marriage and her future husband; instead of one page of lovesickness, she gets several ridiculous minutes of bizarre “Hopelessly Devoted to You”-inspired insanity. Throughout this time she looks foolish, because Ronald is obviously a git. He is so awful, in fact, that he leaves Elizabeth to die in the dragon attack, literally barring his doors.

Still, she decides to save him. This is where things get a bit weird. Elizabeth does not merely follow the trail of burnt forests and horses’ bones, but a path comprised of fairy tale scenarios. She saves Hansel and Gretel from the witch, escapes from the three bears who have mistaken her for Goldilocks, and alerts a golf club-wielding Grandmother to the fact that the wolf is lying in her bed. It’s a bizarre interlude that may or may not be filler, albeit filler that portrays Elizabeth as a proactive problem-solver.

The showdown with the dragon and the exchange between Ronald and Elizabeth follow the book fairly closely, until the dragon wakes up. Why does he wake up, when the whole point of the showdown was that he would be taken out of commission? Because the adaptation can’t quite deal with the idea of Elizabeth being awesome on her own. The writers were clearly more interested in the dragon anyway, giving him more songs and at least equal screentime. When Elizabeth stands up to Ronald, the narration states that “the dragon looked at Elizabeth. She was acting like a dragon herself.” Considering the fact that all we’ve seen the dragon do by this point is destroy property, discuss his many mass murders, and rap truly atrocious songs, this is hardly the praise the show wants us to think it is.

Instead of Ronald leaving on his own, the dragon tells him, “You heard what the lady said,” and promptly lights the seat of his pants on fire. When Elizabeth sings a reprise of her song, she concludes that she doesn’t need a guy, or at least not a jerk like Ronald. However, she makes this assertion while an image of her dancing with the dragon plays across the screen. In the final shot, Elizabeth flies off with the dragon into the same sunset that her book counterpart skipped into alone. While she explicitly rejects her earlier dependence on male humans, she nevertheless relies on a male dragon. She also promptly instructs the dragon in the art of social conventions and niceties, because apparently the same girl who walked off into the sunset wearing only a paper bag, gleefully defying social expectations, is actually really into teaching others the rules of etiquette.

Verdict: Strong Female Character ™

Sadly, the television adaptation is not the worst work derived from The Paper Bag Princess.

That honour goes to Hello Kelly’s 2010 song, “Paper Bag Princess,” a

track that so obviously misses the point of the story it’s hard to

believe anyone involved actually read it. This failure is made all the

more epic by the fact that there are only twelve partial pages of text

in the book.

Again, the lyrics must be seen (or heard) to be believed:

It’s tempting just to leave this here; no comment is really necessary. At the same time, we’d like to take our own dollar store broadswords and eviscerate this song. It is a perfect demonstration of the way in which people can misinterpret and manipulate woman-positive texts to suit patriarchal norms. This Elizabeth shares nothing with the paper bag princess except her name and her outfit.

The major problem lies in the narrator of the song: a boy in love with Elizabeth who nevertheless sees the real girl about as clearly as Ronald does. He frames her positive qualities in terms of what he finds attractive, stating that he has “been waiting a long time for someone like [her]”. He goes even further, suggesting that despite the problems that he thinks she faces -- a list which notably does not include being woefully misread by some idiot with tin foil on his shoulders -- he loves her and that should be enough. Even worse, she is apparently healed by his love and his ownership (because we should remember that she is his, just in case we forget that even though he’s portraying himself as her prize, she is still an object). The message of independence is completely lost in translation.

What is even more impressive is the way in which the narrator fails to understand the true meaning of the paper bag. He suggests that the bag and the dirt that covers her body are marks of her insecurity, which is patently ridiculous; the paper bag is, initially, just a concession to the need to be clothed, and at the end, it is actually the proof of her unquestioning acceptance of herself, regardless of what others think. In addition, insecure people are not going to try to rock a paper bag dress. (Yes, we understand that they’re using the paper bag metaphorically, but Munsch’s metaphor was better.)

In summary, this song may actually outdo Taylor Swift’s “Love Story” in terms of missing the point of the reference text.

Verdict: Love Interest

Robert Munsch is known for his oral storytelling methods and performances, so it is no surprise that one of his stories has been re-told in several versions. One of the great assets of oral storytelling lies in the fact that no telling is ever exactly like another. Even Munsch’s own recorded readings of The Paper Bag Princess differ somewhat from the text.

Indeed, the text and its illustrations have undergone a few changes themselves. In the original draft, Munsch had Elizabeth punching the rather deserving Ronald, and Martchenko’s final drawing once depicted an Elizabeth who had cast off her paper bag, skipping into the sunset naked and completely free of all social convention.

However, those changes are changes of degree, not of kind. A television episode that leaves the ultra-independent, capable Elizabeth of the book with a dragon companion/enforcer and the hope of meeting a better guy is not really telling the same story. A song that appropriates a symbol of feminine freedom only to enforce systematically all of the things the original defies is more of an affront than an adaptation. An Elizabeth derived from either of these two versions would do better to wear the paper bag on her head than on her body.

There is ample evidence of this phenomenon. Beyond the tabloid coverage of real British royalty, we are surrounded by fictional princesses at every turn. Disney has made millions of little girls consider “princess” as a valid career option. ABC’s show, Once Upon a Time, features several members of the official Disney Princess line-up, while NBC has included elements of princess stories in the police-procedural-slash-fairy-tale Grimm. The upcoming Maleficent is set to give us a different take on Sleeping Beauty, while this year’s Mirror Mirror and Snow White and the Huntsman have made Snow White relevant again. Even Stephen Sondheim’s musical, Into the Woods, is getting the Hollywood treatment.

Book

The popularity of the princess is not limited to the silver screen. Indeed, if you walk into almost any bookstore, you will find this week’s featured text. The Paper Bag Princess, written by Robert Munsch and illustrated by Michael Martchenko, has sold over three million copies in multiple languages including Arabic, Chinese, and Flemish. The copy Megan picked up when she couldn’t find the one she was raised with is from the seventieth printing. Munsch did his first readings of the story in 1973 and ‘74, and the book was first published in 1980. A twenty-fifth anniversary edition was released in 2005, and it included a behind-the-scenes look at the classic children’s story.

This is another of our foundational texts. At the same time as we were learning that princesses should sing, talk to animals, and be really, really, ridiculously good-looking, we discovered that this wasn’t the only option. The titular character of The Paper Bag Princess is Elizabeth, a girl introduced as just such a character. When we first meet her, she is beautiful, lives in a castle, wears expensive clothing, and is engaged to marry a prince. By the second page, however, she has lost all of this at the hands of a dragon. And she is Not Amused. Faced with her own lack of clothing, she repurposes a paper bag into a dress and goes to save her prince.

This is the first major subversion of princess-based fairy tales: the prince becomes the damsel in distress. Elizabeth not only decides to save the prince, she chooses to do so immediately after losing everything, including the clothes on her back. She displays immense resourcefulness by first making what must be the only flame-retardant paper bag in existence into a new outfit, then proving that it is the only suit of armour that she will need.

Unlike a fairy tale prince, when she finds the dragon, she doesn’t offer to face him in physical combat. Instead, she frames their conflict as a battle of the wits, knowing that she can use the dragon’s strength against him. This is precisely what she does, appealing to his ego and convincing him through a combination of ludicrous dares and flattery to exhaust himself.

Once the dragon’s out cold, she releases Prince Ronald, and here we get yet another subversion, though admittedly not as delightful as the others. If you read “Just Another Princess Movie,” the article we linked to in the New Age of Princessery post, you are familiar with an argument Lili Loofbourow made: that Merida, having displayed her immense athletic ability and winning her own hand, does not receive cheers, only silence and disapproval. A young woman doing what is not socially acceptable is, in many situations, not going to be praised for her achievement.

Accordingly, Ronald’s first reaction to being saved is not to thank Elizabeth for risking her own life, but to criticize her appearance. Ronald observes, “Elizabeth, you are a mess! You smell like ashes, your hair is all tangled and you are wearing a dirty old paper bag. Come back when you are dressed like a real princess.” In perhaps the most satisfying reply possible, Elizabeth turns his own words back on him: “your clothes are really pretty and your hair is very neat. You look like a real prince, but you are a bum.” Elizabeth has no time for shallow people who evaluate women based on their physical appearance instead of their actual accomplishments. Ronald is unable to look beyond the dirt to see Elizabeth’s BAMF-ness; Elizabeth, however, has learned to see past appearances to Ronald’s rotten core.

For us, the most satisfying sentence may be the last. Having witnessed a distressing number of Disney princess marriages over a period of a little over a month, we find that there are few sweeter phrases than “They didn’t get married after all.”

Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character

TV Show

One of the major issues we will be discussing on this blog is adaptation. We are all used to seeing our favourite comics and books become our slightly less beloved movies and television shows. We know that characters we adore in an original text may not even merit mention in its adaptations. In addition, the nuanced characters of the original may be altered to suit the more streamlined aspect of a single episode or film. This doesn’t always work in female characters’ favour.

Between 1991 and ‘92, a series of television adaptations of Munsch and Martchenko’s stories ran on CTV in Canada, and Showtime and Golden Book Video in the United States. Among the tales adapted: The Paper Bag Princess. Among the tales we wish had not been adapted: The Paper Bag Princess.

The first and most fundamental change occurs in the first sentence. Instead of opening with Elizabeth, the episode begins by establishing the fantasy world and, most importantly, the existence of dragons. Elizabeth is an afterthought, in both the story and her own life. We meet her as she is contemplating a romantic day out with Ronald, and, because this is apparently a Disney movie, she sings about him. Normally, we’d only include snippets of the song in order to make our point, but the lyrics really have to be seen in full:

Since I was a teeny, tiny tike,

I’ve always pictured the man I’d like.

Now that I’m older and almost grown

I’ll tell you ‘bout the kind of guy I want to share my throne:

He’s handsome, he’s young, he’s witty and bright,

His posture is perfect, he’s always polite,

His shoes are shiny, he wears splendid clothes,

He never gets a pimple on his royal nose

He’s a perfect, perfect guy,

Athletic, strong and cute.

He is extremely wealthy

And he’s a prince to boot.

A perfect guy, a perfect guy!

Elizabeth is portrayed as obsessed with marriage and her future husband; instead of one page of lovesickness, she gets several ridiculous minutes of bizarre “Hopelessly Devoted to You”-inspired insanity. Throughout this time she looks foolish, because Ronald is obviously a git. He is so awful, in fact, that he leaves Elizabeth to die in the dragon attack, literally barring his doors.

Still, she decides to save him. This is where things get a bit weird. Elizabeth does not merely follow the trail of burnt forests and horses’ bones, but a path comprised of fairy tale scenarios. She saves Hansel and Gretel from the witch, escapes from the three bears who have mistaken her for Goldilocks, and alerts a golf club-wielding Grandmother to the fact that the wolf is lying in her bed. It’s a bizarre interlude that may or may not be filler, albeit filler that portrays Elizabeth as a proactive problem-solver.

The showdown with the dragon and the exchange between Ronald and Elizabeth follow the book fairly closely, until the dragon wakes up. Why does he wake up, when the whole point of the showdown was that he would be taken out of commission? Because the adaptation can’t quite deal with the idea of Elizabeth being awesome on her own. The writers were clearly more interested in the dragon anyway, giving him more songs and at least equal screentime. When Elizabeth stands up to Ronald, the narration states that “the dragon looked at Elizabeth. She was acting like a dragon herself.” Considering the fact that all we’ve seen the dragon do by this point is destroy property, discuss his many mass murders, and rap truly atrocious songs, this is hardly the praise the show wants us to think it is.

Instead of Ronald leaving on his own, the dragon tells him, “You heard what the lady said,” and promptly lights the seat of his pants on fire. When Elizabeth sings a reprise of her song, she concludes that she doesn’t need a guy, or at least not a jerk like Ronald. However, she makes this assertion while an image of her dancing with the dragon plays across the screen. In the final shot, Elizabeth flies off with the dragon into the same sunset that her book counterpart skipped into alone. While she explicitly rejects her earlier dependence on male humans, she nevertheless relies on a male dragon. She also promptly instructs the dragon in the art of social conventions and niceties, because apparently the same girl who walked off into the sunset wearing only a paper bag, gleefully defying social expectations, is actually really into teaching others the rules of etiquette.

Verdict: Strong Female Character ™

Song

Again, the lyrics must be seen (or heard) to be believed:

Hey Elizabeth, don't raise the drawbridge darling.

I've been waiting a long time for someone like you.

For someone like you.

You hide behind your insecurities.

The paper bag around your waist

And the mud upon your face puts them above you.

But I still love you.

‘Cause I'm standing in my tin foil armour,

My dollar store broadsword is by your side.

But you give away your heart ‘cause you think you’re ugly,

So let me hold your arm.

Hey Elizabeth I'm just a peasant school boy.

But I've been waiting a long time to hold your hand,

Or something like that.

I'm not a soldier and I'm not a king,

But I can play a mean guitar

And you can talk to me about almost anything,

Without worrying.

‘Cause I'm standing in my tin foil armour,

My dollar store broadsword is by your side.

But you give away your heart ‘cause you think you’re ugly,

So let me hold your arm.

Hey Elizabeth don't think that I am ok

‘Cause I've got problems just like you, but I am fine.

‘Cause you are mine.

If we put our faith into God above,

Then He will protect us both, and He'll keep us strong

As long as we’ve got love.

And we've got love.

It’s tempting just to leave this here; no comment is really necessary. At the same time, we’d like to take our own dollar store broadswords and eviscerate this song. It is a perfect demonstration of the way in which people can misinterpret and manipulate woman-positive texts to suit patriarchal norms. This Elizabeth shares nothing with the paper bag princess except her name and her outfit.

The major problem lies in the narrator of the song: a boy in love with Elizabeth who nevertheless sees the real girl about as clearly as Ronald does. He frames her positive qualities in terms of what he finds attractive, stating that he has “been waiting a long time for someone like [her]”. He goes even further, suggesting that despite the problems that he thinks she faces -- a list which notably does not include being woefully misread by some idiot with tin foil on his shoulders -- he loves her and that should be enough. Even worse, she is apparently healed by his love and his ownership (because we should remember that she is his, just in case we forget that even though he’s portraying himself as her prize, she is still an object). The message of independence is completely lost in translation.

What is even more impressive is the way in which the narrator fails to understand the true meaning of the paper bag. He suggests that the bag and the dirt that covers her body are marks of her insecurity, which is patently ridiculous; the paper bag is, initially, just a concession to the need to be clothed, and at the end, it is actually the proof of her unquestioning acceptance of herself, regardless of what others think. In addition, insecure people are not going to try to rock a paper bag dress. (Yes, we understand that they’re using the paper bag metaphorically, but Munsch’s metaphor was better.)

In summary, this song may actually outdo Taylor Swift’s “Love Story” in terms of missing the point of the reference text.

Verdict: Love Interest

Conclusion

Robert Munsch is known for his oral storytelling methods and performances, so it is no surprise that one of his stories has been re-told in several versions. One of the great assets of oral storytelling lies in the fact that no telling is ever exactly like another. Even Munsch’s own recorded readings of The Paper Bag Princess differ somewhat from the text.

Indeed, the text and its illustrations have undergone a few changes themselves. In the original draft, Munsch had Elizabeth punching the rather deserving Ronald, and Martchenko’s final drawing once depicted an Elizabeth who had cast off her paper bag, skipping into the sunset naked and completely free of all social convention.

However, those changes are changes of degree, not of kind. A television episode that leaves the ultra-independent, capable Elizabeth of the book with a dragon companion/enforcer and the hope of meeting a better guy is not really telling the same story. A song that appropriates a symbol of feminine freedom only to enforce systematically all of the things the original defies is more of an affront than an adaptation. An Elizabeth derived from either of these two versions would do better to wear the paper bag on her head than on her body.

Friday 5 October 2012

The Mothers

Disney has a problem with mothers. This is incontrovertible fact. However, just as the Disney princesses have developed over the decades, so too have their mothers; some of them are even still alive during the events of the film!

In this post we have limited ourselves to discussing only those mothers and mother figures whose daughters we have already mentioned. We will also only be dealing with the original films. Sorry, The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginning, a sequel we didn’t even know existed before writing the princess series.

In all seriousness, there is a lot to say about Disney mothers, especially those who could easily be credited as Lady Not-Appearing-in-This-Film. The princesses have historically been defined by their relationships to their fathers and to their male love interests, and when women play a major role in their development, it is almost invariably as an antagonist. Still, we find ourselves fascinated by the women who have a hand in shaping these characters.

The M.I.L.L.s

The above acronym stands for Mothers I’d Like to Live, the group of mothers who died before the story begins and whose presence is hardly even missed in the narrative. It particularly describes the mothers of Ariel, Belle, and Jasmine, although Jasmine’s mother is given one mention; the Sultan complains about Jasmine’s reluctance to get married, stating, “I don’t know where she gets it from. Her mother wasn’t nearly so picky.” The maternal absence in each of these films is fascinating, especially in light of the important roles played by each woman’s father.

It is also interesting in light of the tremendous female presence in the first three Disney princess films. Whereas all three of these princesses have some sort of maternal figure, wicked or otherwise, the revival characters seem to be produced primarily by men, almost as if through asexual reproduction. This is partially the fault of the source material; “Beauty and the Beast” has always been about the protagonist’s father doing something foolish, and the Sea King is a widower in Hans Christian Andersen’s story. We can’t help but wonder if there’s more to the lack of mothers, though. Perhaps Disney was reluctant to go the wicked stepmother route in their portrayals of independent, adventurous females, as if antagonistic maternal figures would make the story too domestic for characters looking for adventure in the great, wide somewhere. Perhaps in removing the maternal figure altogether, Disney was trying to make the revival princesses seem more self-reliant -- these are women who don’t need their mommies. Perhaps they wanted a completely different kind of princess to mark their rebirth. Perhaps, and this is probably the most depressing and most likely option, they just didn’t notice.

The Living Dead

Disney has featured so many characters with dead mothers that we can split them into two categories. This one includes all those mothers who, despite dying, have managed to remain relevant to the plot.

Pocahontas’ mother is the first to achieve this distinction. Before we see Pocahontas for the first time, we learn that she is very much her mother’s daughter. She has her mother’s spirit and “goes wherever the wind takes her.” It is her mother’s necklace that Powhatan gives to Pocahontas, telling her that her mother had wanted Pocahontas to wear her mother’s necklace at her own wedding. Pocahontas wears it for the rest of the film. It also suggested on several occasions that her mother has become a kind of wind spirit; considering the integral role the wind plays in most of the key scenes (John Smith and Pocahontas’ first meeting, “Colours of the Wind,” and Pocahontas’ race to save John Smith), it would be fair to say that her mother orchestrates much of the story. She also plays matchmaker for her daughter and, were it not in the service of securing peace, it might be a little creepy. However, what is perhaps most interesting about her mother’s influence is the way in which it allows the film to subvert the usual tropes of the princess series: Pocahontas essentially gives up on true love in order to remain with her people. Powhatan had earlier observed that the people looked up to her mother for wisdom and strength, and Pocahontas clearly takes on her mother’s legacy, just as she took on her necklace.

The other mother in this category is the queen of Atlantis. Unlike Pocahontas’ mother, she has a corporeal presence in the world of the film. We meet her at the same time as we meet Kida: as Atlantis begins its descent into the depths. Indeed, it is Kida’s mother who preserves the city, having been taken by the Heart of Atlantis to form a protective force field around the city. Kida, traumatized after having her mother literally pried from her fingers, becomes obsessed with their history and culture in order to find an explanation for her mother’s disappearance. When she follows in her mother’s footsteps and is also chosen to be absorbed by the Heart of Atlantis, it appears as if Kida has at last managed to make some contact with her mother. She returns with the bracelet her mother had slipped from her wrist as she ascended to the Heart.

Both of these characters are represented by objects, as if to provide them with some solid, if indirect, presence in the world of the film. The fact that these objects are worn by their daughters suggests that they have a hand in their daughters’ accomplishments.

The Just There Moms

This group includes the mothers of Mulan, Aurora, Rapunzel, and Tiana. Mulan’s story revolves her taking her father’s place in order to earn his respect, so it is not surprise that her mother plays a secondary role. She doesn’t even get to provide some comic relief, as that role is already filled by Mulan’s grandmother. Fa Li basically gives Mulan a makeover and helps her husband deliver the exposition that Mulan will be killed if they reveal that she is a woman. However, she is the first mother of a “princess” to be alive in the film since Sleeping Beauty, which is an accomplishment in itself.

Aurora’s mother, whose name is apparently Leah, just exists. She gets a single line, and even gets passed over in the fairies’ line about the people waiting for Aurora at home.

Rapunzel’s mother, the nameless Queen, serves the plot in a very passive way. While pregnant with Rapunzel, she falls ill and must be healed by the flower that gives Rapunzel her powers. Other than that, she generally just looks sad. At the same time, she represents a subtle but interesting shift in perception. Whereas Aurora was returned first and foremost to King Stefan, Rapunzel is greeted first by her mother. It is her mother whose grief we follow more closely, and it is she who identifies the newly brunette daughter she lost.

Despite being voiced by Oprah, Eudora does not buy a restaurant for Tiana; instead, she serves as a kind of guide into the realm of fairy tales. She is the one who reads the story of the frog prince to Tiana and Charlotte while helping to cement Charlotte’s obsession with princesses by making her elaborate dresses. Later, when Tiana is an adult, she tries to relay her husband’s message that Tiana should focus on personal relationships as well as work; he didn’t get his restaurant, Eudora concedes, “but he had something better. He had love. And that’s all I want for you, sweetheart: to meet your Prince Charming and dance off into your happily-ever-after.” Needless to say, Eudora’s not our favourite Disney mom.

The Wicked Stepmothers

This is perhaps Disney’s favourite kind of mother. You can tell by the almost palpable glee the writers and animators took in depicting these truly awful human beings. Numbered among this group’s members are Snow White’s wicked stepmother (which is her actual description in the storybook opening), Lady Tremaine, and Mother Gothel.

The first of these ladies is the most overtly, single-mindedly evil of the lot. Obsessed with her own beauty, the Queen orders the huntsman to kill Snow White the moment she learns that she has been dethroned as the “fairest one of all.” When she learns that her rival is still alive, she decides that if you want something done right, you’ve got to disguise yourself as a hag, cook up a poisoned apple, travel through the woods, and do it yourself. Then she dies ugly, ‘cause payback’s a bitch.

Lady Tremaine seems slightly less evil, if only because you can see that the awful things she does are technically intended to benefit her own daughters. She is described in the voice-over as “cold, cruel, and bitterly jealous of Cinderella’s charm and beauty.” We’re more than a little troubled by the idea that the antagonistic relationships that Cinderella and Snow White have with their respective stepmothers stem explicitly from jealousy over their beauty. It is as if no more legitimate reason for their hatred needs to be provided, because physical attractiveness is all that matters. Still, you’ve got to hand it to Lady Tremaine; she knows how to crush a spirit. Using Cinderella’s own hope against her, she allows her stepdaughter to believe that she might attend the ball, only to destroy this dream at the moment Cinderella is certain it will come true. This is a wicked stepmother that I could see instructing her daughters to cut off bits of their feet so they can become queens.

Then there’s Mother Gothel, who, with a few precise verbal incisions, can remove her daughter’s entire self-esteem. For those who claim to see Stockholm Syndrome in Beauty and the Beast, turn your eyes to this doozy of a mother-daughter relationship and witness the real thing. Watching this film, we found it particularly irritating to see Rapunzel let down both her hair and herself from the tower, as it proved that she could have done it at any time. However, it is clear that Gothel’s eighteen-year annihilation of her self-confidence kept Rapunzel inside. Gothel’s methods are insidious because she disguises so many of her controlling messages with seemingly caring sentiments. She ends discussions with a show of her devotion (“I love you very much, dear.” “I love you more.” “I love you most.”) which only serves to make her behaviour that much more chilling because, in a way, she really does love Rapunzel. She makes her favourite foods, journeys for days in order to make her special paints, and likely teaches her at least some of the many activities she uses to occupy herself. However, we know that when she says, “I love you most,” she’s really talking to Rapunzel’s hair.

The Maternal Figures

This category exists purely so we can talk about the good fairies and Lilo’s sister, Nani, something that we do often, at length, in our real lives.

The good fairies take Aurora in as an infant and raise her as their own. They do this despite knowing nothing about child rearing or domestic upkeep. They also do this without the assistance of the wands on which they have evidently relied for their entire lives. Still, they know that they must protect her for the good of the kingdom, so they are willing to make a sacrifice that, despite being played as a joke, is actually quite impressive.

Although she is technically Lilo’s sister, their parents’ death forces Nani to become a kind of single mother at nineteen. She must work a low-paying job, prepare meals, and do the chores, all while taking care of the bizarre Lilo. And she can’t keep up, but the film never really blames her for that, because Nani tries so hard. When Lilo wants a friend, she agrees to get her a pet. When Lilo wants the ugly, blue, possibly undead dog, Nani lends her the money so Lilo can claim Stitch as her own. When said blue dog makes Nani lose her job and, potentially, Lilo, Nani works to find a new position literally anywhere. Although Lilo and Stitch both bring up the concept of “ohana,” it is Nani who embodies it. Her life would be infinitely easier if she didn’t have to take care of Lilo, but instead of giving herself freedom, she strives at every opportunity to keep her family together.

The Co-Protagonist

Here is where we come clean with another disclaimer: this entire post was initially planned just so we could talk about the greatest of Disney mothers, Elinor. Yes, we’re fangirls. No, we’re not sorry.

There’s no reason to apologize for fangirling a character as nuanced and fascinating as Elinor, queen of DunBroch. Although her husband was selected to be king, it is Elinor who both literally and figuratively wears the crown; his military prowess gained him the title, but her diplomacy secures it. She also orchestrates the search for the next king and, when the current one cannot remember the lines she obviously wrote for him, she runs the betrothal competition herself. She controls a room merely by walking through it, because she commands respect. In her voice-over, Merida complains, “I'm the princess. I'm the example. I’ve got duties, responsibilities, expectations. My whole life is planned out, until the day I become, well, my mother. She's in charge of every single day of my life.” To cap off this same scene, Elinor sums up the duty of a female sovereign-in-training: “above all, a princess strives for...well, perfection!” It is obvious that Elinor holds herself to the same standard, and the gray streak in her hair is a visual reminder of the toll her need to maintain perfection takes.

The central object in the film, the tapestry depicting the family DunBroch, is proof of this obsession with perfection. Faced with the reality of her boisterous husband, her mischievous sons, and her rebellious daughter, Elinor instead portrays them as a flawless, static family, even going so far as to tame Merida’s wild curls. When Merida slices through the false Elinor and Merida’s handhold, she not only ruins the tapestry, but destroys the image of the perfect family that Elinor needs to project.

There are also more profound implications for Merida’s rash act. Elinor is portrayed as the keeper of tradition and history, using this history in its narrative form as legend to impart knowledge of the kingdom’s past to the next ruler. Telling Merida the story of the fourth brother and the kingdom he caused to topple, she observes that “legends are lessons and they ring with truths.” In telling these stories, Elinor demonstrates that she is not just a maker of laws but a maker of meaning. Her work, then, carries great weight. The tapestry is an ideal image, but it is also an artifact depicting the first monarchs of a new kingdom. Merida physically destroys historical evidence of their reign and, in slicing through the handhold, symbolically severs the link between one ruler and the next.

And then we come to the more literal implications of this destructive act; by cutting through the handhold, Merida makes evident the rift between mother and daughter that forms the crux of this film. When we first meet Elinor, she is playing with Merida, pretending to be a monster that will gobble her child up. It’s a situation rarely seen in films: a mother just having fun with her daughter. Later, in a flashback, we see the seemingly stoic Elinor’s devotion to Merida, as she promises her daughter that she will always be there for her. But there is a difference between being physically present and being supportive. By the time Merida is a teenager, Elinor’s actions are primarily motivated by her concern for the good of the kingdom. As Merida tries to tell her mother about her climb up to the Fire Falls, Elinor reads the acceptance letters from the three lords; while Merida practically begs Elinor to acknowledge her as a person, Elinor is planning her fate as a political tool. As a badass queen trying to train a ruler of equal or greater badassery, she forgets that said heir is her daughter.

And it comes back to bite her. As we observed in our discussion of Merida, one of the things we really love about this film is the fact that everything is driven by women’s agency, and the main focus of the plot – Elinor being turned into a bear – is no exception. It is the result of both women’s actions, as Merida slices through the tapestry and Elinor responds by throwing Merida’s bow – the symbol of her freedom and identity – into the fire. The difference is that Elinor immediately regrets her actions, while Merida decides to order a spell that will change her fate by circumventing her mother’s own agency.

So much of femininity – and, accordingly, so much of this film – is about performance, and transforming the image-conscious Elinor into a bear is like giving her a script entirely written in Klingon. She must try to adjust to the inherent horror of having her body changed into a hulking mass of muscle and fur, but she must also adjust to the collapse of social conventions. When Elinor tries to cover her now gargantuan body, Merida’s admonishes her, saying, “You’re covered with fur. You’re not naked!” She is essentially saying, “As an animal, you are no longer bound by socially constructed concepts like the shame of nakedness,” and that is incredibly difficult for Elinor to accept. However, though she is stripped of the social power she once wielded, she does gain the strength of ten men. Her arc revolves around learning to use physical skills and raw brawn, as Merida does. Merida, in return, must learn to employ social might in the style of Elinor. They adopt each other’s preferred models of badassery and, in so doing, come to a new understanding and appreciation of each other.

Now we come to what is perhaps our favourite thing in a film full of favourite things. In every Disney princess movie, there is some kind of implicit or explicit heterosexual romantic relationship, and many of these films revolve around the adventures of their respective couples. This is where Brave makes its most interesting change to the Disney princess model: by not giving its protagonist a love interest. Sure, Elinor has an utterly lovely marriage, but the actual princess spends most of her time being terrified by the prospect; as Merida herself says, “the princess is not ready for this. In fact, she might not ever be ready for this! So that's that!” Instead, Brave makes her mother the love interest, replacing romantic love with familial love as its focus.

The depths of this love are revealed in a number of subtle ways; a particular favourite of ours is the moment when Merida sees the transformed Elinor for the first time and screams “Bear,” causing Elinor immediately to lunge in front of her and fling a paw over her in protection. When it is necessary, both women risk their lives to protect the other. What is truly fascinating, however, is the way in which the film employs and subverts the tired Disney romantic tropes. There is a montage of Merida and Elinor getting to enjoy being around each other as people again, replacing the usual scene in which the romantic couple

begins to realize their feelings for each other. For reference, think the montage set in the city square in Tangled. The song playing over it is quite evidently a love song, beginning with lyrics to that effect: “This love, it is a distant star / Guiding us home wherever we are / This love, it is a burning sun / Shining light on the things that we've done.” The moment just before Elinor returns to human form, in which Merida pleads, “I want you back, mummy. I love you,” is reminiscent of the similarly blocked scene from Beauty and the Beast. In the end of the movie, we even see Elinor and Merida basically ride off into the sunset together.

Of course, we have to end talk of Pixar’s “girl movie” with a brief discussion of fashion. While Merida ends up garbed like a king, Elinor undergoes an equally interesting sartorial transformation. First and most obviously, her hair is unbound, signifying her more easygoing existence. She has also not taken up the crown that she abandoned in the woods while she was a bear, leaving behind her obsession with royal appearance. Finally, she wears a blue dress, a colour strongly identified with Merida. As Elinor observes, they’ve both changed, and we can actually see the proof.

Okay, we lied. We had to end this with a mention of that second tapestry, depicting Merida and the affectionately named Mumbear, because we love the idea that this story becomes another piece of history and legend. We particularly love what so many people disliked about the film: it’s a girls’ story. Except, of course, we mean that quite literally. This is history chronicled by women, who have a voice and a say in how they are portrayed. And it’s awesome.

Conclusion

As the princesses have evolved, so too have their mothers. Gone (we hope) are the wicked stepmothers obsessed with youth and beauty, the non-entities that don’t even warrant a mention in the script, and the moms who stick around just long enough to make it into the credits. We’re ready for a new trend in Disney mothers: living, active women who are interesting characters in their own right.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)