Once upon a time, in a faraway land (depending on your own geographical location), two recent university graduates decided to write a blog about the representation of women in media. “But where should we begin?” they wondered. Then it struck them: once upon a time...

Very

few female characters are more beloved or more derided than Disney

princesses. It’s easy to embrace their dreams of love and freedom, but

it’s equally easy to spot the flaws in a life plan based entirely on

wishes and the hope for some nebulous happily-ever-after. For many of

us, Disney princesses are our first guides as we enter the realm of

media consumption, first lighting up our screens and then adorning our

bedrooms. Their films are our foundational texts, and we want to use

them to build another foundation.

In

the next few weeks, we’re going to be writing about four distinct

groups of princesses, one group of characters who didn’t quite qualify

for the coveted title, and one group of Disney mothers, those

ever-elusive figures. To kick things off, we’re looking at Disney’s

first three princesses, the ones that started a massive franchise that

would become a requisite element of many girls’ childhoods.

Snow White

Debuting

in 1937 and thus celebrating her seventy-fifth birthday this year, Snow

White is Disney’s first princess. We also think she’s the worst. Due

to Snow White’s popularity this year -- the story retold in two major

Hollywood films and a television show -- one could say that we’re in the

minority. However, in all of those adaptations, including the one set

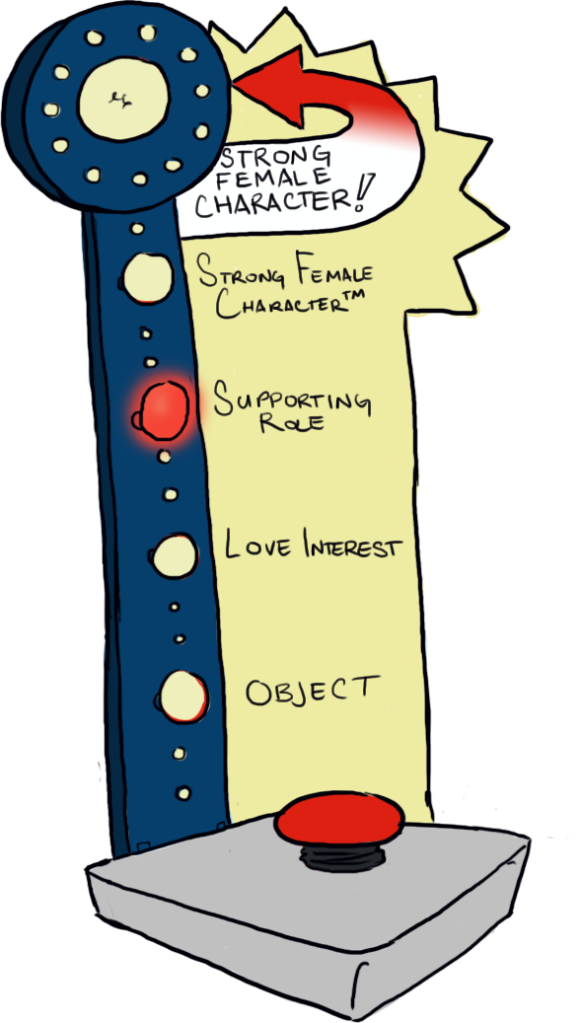

in a Disney-inspired world, Snow White gets an upgrade on the Strong

Female Character scale. The princess progenitor Snow White is hardly

the same one we see today.

This

is for good reason. We are introduced to Snow White as a “lovely

little Princess” forced to work and dress as a scullery maid whose “rags

cannot hide her gentle grace.” When the queen consults with her magic

mirror, only to learn that she has been dethroned as the fairest one of

all, she doesn’t even have to hear Snow White’s name to know that it’s

her. With “lips red as the rose, hair black as ebony, skin white as

snow,” the princess so aesthetically towers over everyone else that she

can be identified just by what actually sounds like a slightly

terrifying list of physical features. She is beautiful, and this is her

defining trait.

There’s

not much else to her. She sings two “I Want” songs, which usually

function to help the audience to get to know a character through the

sung-through revelation of their most profound desires; in this case,

however, all we learn is that she wants to meet and marry a handsome

prince. After she learns that her stepmother put a hit out on her and

understandably has a bit of a breakdown as she runs through the forest,

she apologizes for her actions: “But you don’t know what I’ve been

through / And all because I was afraid / I’m so ashamed of the fuss I’ve

made.” It’s almost as if she’s apologizing for experiencing human

emotion. When she then trespasses on the dwarfs’ property, she shames

the absent owners as if she were in an episode of How Clean Is Your House?,

then cleans the cottage based on the logic that the first thing people

will do when they learn that someone has been in their house for hours,

rearranging their personal belongings and cleaning everything with the

help of woodland creatures, is to invite them to stay. Whereas these

personality flaws might be interesting if they were treated as flaws,

the film continues to support Snow White’s behaviour. ‘Cause she’s

pretty and well-meaning.

The

film does not continue to feature Snow White, though. Once the dwarfs

arrive on the scene, and for something like ⅝ of the film, they become

both our focus and our true protagonists. This is not just a problem

with the film, but is actually the most salient problem with Snow White

as a character: she’s boring and, ultimately, inactive. The way that we

seek to define strength on this blog has a lot to do with the agency

that a character exercises, and the most agency Snow White displays is

in breaking and entering and bowing to pressure to eat a “magic wishing

apple.” She lacks a character arc, something which Grumpy, of all

people, achieves. She puts herself to sleep, but she doesn’t wake

herself up, and she doesn’t defeat her nemesis; the dwarfs and woodland

creatures take care of the latter, while the prince that Snow White met

once for less than five minutes accomplishes the former using Love’s

First Kiss.

As if all of this weren’t enough, she regularly speaks in verse.

Cinderella

In

1950, Disney took a more successful crack at making a more realistic

princess. Cinderella is easily the strongest of these three princesses

and, we would argue, the real progenitor of the Disney princess tradition as it exists today.

Cinderella

is imbued with a human quality which Snow White lacks. This is

partially a result of the film’s explicit acknowledgement of the horror

of her abuse. Snow White enjoys the domestic chores she is forced to do

in her guise of a scullery maid, whistling while she works.

Cinderella, by contrast, clearly performs a number of physically

demanding chores from which singing offers only temporary respite.

Whereas Snow White only subtextually resents her isolation, suggested

by her desire to be taken away from it by that handsome prince,

Cinderella openly complains about the unfairness of her situation.

Although she displays the same unflagging optimism as her predecessor,

she also expresses real annoyance at her treatment.

What further intrigued us in re-watching Cinderella

was her maturity and genuine gratefulness. Even though her stated life

philosophy suggests that her fairy godmother would one day come along

and fix everything for her, Cinderella is happy with what she receives,

midnight curfew and all.

Still,

she lacks real agency. Although her own “I Wish” song -- “A Dream Is a

Wish Your Heart Makes” -- does not revolve around a man saving her from

her plight, it continues to perpetuate an ultimately disempowering outlook:

A dream is a wish your heart makes

When you're fast asleep

In dreams you lose your heartaches

Whatever you wish for, you keep

Have faith in your dreams and someday

Your rainbow will come smiling through

No matter how your heart is grieving

If you keep on believing

The dream that you wish will come true.

It’s

about hoping for something to change without one’s own involvement,

promoting escapism over action. The film obviously believes its

character’s words, because Cinderella takes almost no action at all.

The talking mice make her the dress which would have enabled her to

attend the ball, and when it is destroyed, her fairy godmother appears

with a well-placed “Bibbidi bobbidi boo.” When she is imprisoned in her

own home, her animal friends steal the key and release her. The only

thing Cinderella actually does is produce the second glass slipper after

the first shatters, ensuring her own happy ending after everyone else

has done the heavy lifting.

Aurora/Briar Rose

While technically a Disney princess film, Sleeping Beauty (1959) is not Aurora’s story; rather, it is the story of the three fairies who protect her.

Aurora, renamed Briar Rose when she goes underground to avoid Maleficent’s ire, is a generic Disney princess only two films after the trope was created. Like her predecessors, she communicates with animals and falls for her “true love” after a single meeting. And she falls hard. When Briar Rose learns her true identity as the Princess Aurora, she weeps not upon discovering the years of lying masterminded by her “aunts,” but when she is told that she can’t date the stranger from the woods whose name she obviously didn’t even ask.

With Aurora/Briar Rose, Disney brings back the idea that a woman’s greatest dream would be for a man to marry her. Aurora dreams of a dance partner and, as she states, “They say if you dream a thing more than once, it’s sure to come true. And I’ve seen him so many times.” This is right in line with Cinderella’s idea that hope inevitably produces that which is hoped for. However, the problem with a worldview which holds that wishing on a star produces tangible results is not only the crushing disappointment when these results don’t actually result, but the inactivity which it promotes. If wishes always come true regardless of what you do, why do anything?

What is interesting about this film is that it has slipped in some stronger female characters in the form of the good fairies. They do all the work, yet they get only a small fraction of the publicity and merchandise. Not only do they drive the plot by saving Aurora from her future untimely death and by taking on the task of raising her, they also become the real heroes in the climactic scene. They break Philip out of the dungeon, give him magical hardware, turn projectiles into harmless bubbles and flowers and, in one memorable instance, transform hot oil or tar into a rainbow. In fact, they even aim his sword and thereby defeat Maleficent. Because we like to pretend that we’re above making jokes about phallic symbolism, we’ll let the readers interpret that one.

Conclusion

We

do concede that these three characters were unmistakably produced by

the attitudes of their respective times. However, we think that, while

these films may warrant discussion as historical documents, the

princesses themselves are affecting the worldviews of children to this

day, as role models and figures for identification. These three films

are frequently re-released and few Disney princess products are without

the image of at least one of these characters. A quick Google Image

search for “Disney princesses” produces pages upon pages of images

containing Snow White, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty together with

newer Princesses, and the central position in the group often goes to

one of these “First Three”. The first thing one sees at the official Disney Princess website is a lineup of the Princesses, with Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty

flanking Rapunzel and Tiana (the group’s two newest official members) in

the centre of the image. The central focus these three occupy in

marketing is especially ironic when you consider that, while these

princesses are the title characters of their respective films, they’re

not really the main characters. In a very real way, these characters

never play more than a supporting role in their own stories.

Our verdict: they all play supporting roles.

Our verdict: they all play supporting roles.