One of the problems with what we call the Strong Female Character™ is their simultaneous ubiquity and rarity; just about every comic, film or television show has to have one, but quite often one seems to be the limit. They’re the Love Interest, the Girl, the token, and the representational weight of one half of the population falls on their invariably slim shoulders. Even those characters that manage to achieve realistic complexity can be crushed under the massive form of the Everywoman.

There is no such problem in the series that I will be discussing for the next several posts: Brian K. Vaughan and Pia Guerra’s Y: The Last Man. As suggested by the title, the series tells the story of the last man on Earth. In 2002, a mysterious plague instantaneously wipes out every creature with a Y chromosome, save for one unemployed English major/escape artist and his disobedient capuchin monkey. When the gendercide hits, Yorick is proposing to his girlfriend, Beth, via phone call, and the rest of the series follows his quest to reunite with her.

“It figures,” one character observes halfway through the series, “An entire planet of women, and the one guy gets to be the lead.” To Vaughan’s credit, however, while Yorick struggles to stay afloat in a sea of existential angst, the series uses his journey to depict the all-female population’s efforts to ensure the continuation of the species and the establishment of a matriarchal society. Yorick is the last man, but it’s the last women who drive the story.

Dr. Allison Mann

The first thing to know about Dr. Mann is that she’s the best of the best. She tenured at Harvard before the age of thirty, and her papers bring other scientists to tears with their perfection. The finest scientific mind in the United States, who “knows more about asexual reproduction than anyone alive,” Dr. Mann is introduced giving birth to her own clone. When Yorick tells her she’s a god, she replies, “Yes. I know.” She’s the kind of person who didn’t need half the population to die to be considered exceptional. Dr. Mann is formally introduced as humanity’s best hope for survival. Yorick, accompanied by his bodyguard, Agent 355, an ultra-competent member of a secret paramilitary organization dating back to the time of George Washington, is sent to find Dr. Mann. She is tasked with finding out and reproducing whatever protected Yorick and Ampersand from the plague as well as mastering the creation of viable human clones. Without her, Yorick is merely an anomaly.

Unfortunately, when Yorick and 355 find her, she has given up on cloning, saying, “I just want to do whatever I can to make up for my stupid mistake… so I can kill myself in good conscience.” Joining Yorick’s quest is, initially, a matter of seeking absolution. However, a year and a half later, she reveals that the male fetus she claimed to be carrying was actually female. Now relatively certain that she didn’t cause the plague, she still lacks faith in her own abilities. To her, the baby’s sex matters because “it means I’m a fucking failure!” Her self-described “shoddy science” could easily prevent her from successfully cloning anyone. Compounding the difficulty of her already nearly impossible task is her own self-doubt.

Allison Mann has a complicated relationship to her ego, her identity, and her sense of self. Early in their journey, Yorick makes a comment about “someone like you,” and she immediately gets defensive about her mixed Chinese and Japanese background, even though it turns out that Yorick was talking about something completely unrelated. Later, she speaks English to her Chinese mother, who demands that she switch to one of her parents’ languages. On some level, she wants to sever ties to her own history, to any part of herself that she did not create. This extends to her reluctance to reveal her real name, despite the fact that she admits early on that “Allison Mann” is a fabrication derived from Mann’s Chinese Theater: “something kitsch-y and faux-Asian to insult my father.”

The key to understanding Dr. Mann -- AKA Ayuko Matsumori -- lies in her construction of “Allison Mann.” Although she argues that her self-naming was a “dumb teenage rebellion thing,” it’s clearly much more than that. She uses her new identity to separate herself from her father, the man who controlled her life until he disowned her for being a lesbian. It was likely at this time, when they renounced their familial ties, that she became Allison Mann. This is the name that she hopes will go down in history when she gives birth to the first viable human clone, a project that she begins not for the sake of scientific progress, but for bragging rights over her father. She makes a point of detaching herself from her father but, in so doing, strengthens the attachment. Instead of working for herself, she works against him. “Allison Mann” is important because it is the name Ayuko Matsumori gave herself, but it is perhaps more important because it is not the name her father gave her.

This changes when she sees her father for the last time. It turns out that Dr. Matsumori managed to survive the plague because he (probably) caused it. (The series never confirms the veracity of his story, but there is something to be said for the fact that it explains more than any other theory put forward.) Whereas she began her cloning project to beat him, he started his to remake her, viewing the clones as opportunities to fix the mistakes he made while raising her. He was responsible for the death of her fetus, and he plans to finish sabotaging her work by killing Yorick. This drives Allison to fight back, asserting her identity and her agency: “My name is Doctor Allison Mann, and your hostage is my patient.” She claims responsibility for keeping Yorick alive and vows to bring men back to the planet.

Most importantly, however, she finally finds a way to separate herself from her father through the things she has learned on her journey. She accuses him of letting his ego get in the way of his science, and he turns the accusation back on her, asking her how she’s any different. She responds, “Because I learn from my mistakes. I care about people other than myself, and I owe it to them to get this right. I will get it right.” Her accomplishments are no longer driven by hubris and a need to outdo the man who rejected her; instead, she finds confidence in the good she can do for the people who give her love and support. Her self-chosen name no longer reinforces her connection to her father, but severs it. Finally, in a moment loaded with symbolism, one of the Ayuko clones distracts her father and gives Allison the chance to kill him. After he dies, Allison hugs her younger self and tells her that she’s sorry: Dr. Allison Mann embracing Ayuko Matsumori and apologizing for all of the suffering that they have had to endure.

What sets Allison apart from her father also differentiates her from the Dr. Mann who began the journey with Yorick and 355 four years earlier. In the time just before the plague hits, Allison is at her most self-centered, literally growing another version of herself inside of her in order to prove her superiority over the man who disowned her. The gendercide both undermines and strengthens this self-centeredness, at once awakening Allison to the effects her actions have on others and making her believe that her work was powerful enough to kill billions of people. While she originally joins 355 and Yorick as part of a search for redemption, it is the journey itself that helps her to care for others.

Throughout the series, there are a myriad of references to Dr. Mann’s seeming heartlessness. She claims that her father’s death was the only good thing to come out of the gendercide, interrupts Yorick’s romantic musings with mood-killing logic, and destroys a bonding moment between 355 and Yorick with news of the pygmy shrew’s extinction. Yorick considers her to be robotic, thinking of her as the Tin Man, and she hardly dissuades this way of thinking when she says things like, “Love isn’t an ‘emotion,’ it’s an abstract construct mammals assign to a biological imperative they don’t fully understand.” However, the Tin Man is a more apt analogue than even Yorick might realize: the Tin Woodman of the original books gained his metal body due to an enchantment intended to keep him from the girl he loved, and he retained his emotional tenderness despite -- and, bizarrely, because of -- the removal of his heart. Allison suffers betrayal at the hands of the woman she loves and builds herself a metaphorical suit of armour. Having been abandoned by almost everyone she loves, she forsakes interpersonal connections. Despite this, she largely forsakes violence, believes that everyone deserves the chance to be saved, and risks her own life to help people she’ll never meet. Unlike the Tin Man, she doesn’t need a heart made of velvet and sawdust; she simply needs a reminder that hers is still in her chest.

This reminder comes from three sources: Yorick, 355, and Rose. When she clones herself, Allison tells her assistant that they’ll worry about the ethics later. Her friendship with Yorick, born of snarky quips and years spent caring for him both medically and emotionally, helps her to see that there is a person beyond the problem. By the end of their time together, Allison thinks of Yorick not as an experiment but as a friend. In her pivotal moment of self-identification, she includes Yorick: “My name is Doctor Allison Mann, and your hostage is my patient.” In so doing, she makes the care of others part of her identity. Her relationship with Agent 355 is somewhat more complicated. In its early stages, the friendship between Allison and 355 seems to be based mostly on mutual respect and, on Allison’s end, an unrequited crush and a lie intended to get 355 to like her. Still, over time they come to rely on each other as a source of honesty and support. Allison encourages 355 to think of her own needs instead of always tending to the needs of others, while 355 helps Allison to emerge from the critical echo chamber of her own mind. The extent of their devotion to each other is evident in their final goodbye: an exchange of “I love you’s” delivered in gibberish. It’s explained in an earlier issue both that they speak gibberish to keep the content of their conversations secret from Yorick, and that they speak it with incredible ease. This is their shared language, and it is used to discuss important things; its use in this exchange speaks to the value they both place on their relationship.

Allison’s romantic relationship with Rose Copen is the series’ most explicit treatment of her trust issues. Rose is an Australian spy, originally posted to a ship carrying both our heroes and a cargo hold full of heroin. She is ordered to cultivate a relationship with Allison in order to keep tabs on Yorick’s movements, but she soon finds herself falling in love with Allison. Allison, for her part, finds herself drawn to Rose despite her protestations about the inherent falseness of love. When Rose inadvertently reveals her orders to Allison, the doctor feels that her distrust of love has been validated, and she plans to dump Rose before Rose can betray her any further. Rose surprises her, however, and goes AWOL in order to pursue her relationship with Allison. By the end of the series, Rose is pregnant with the first clone of Yorick, having stayed with Allison until her death.

We’ve seen this character arc in its simplest form many times: a self-centered workaholic is reformed through the healing power of love. In many of these stories, this reformation involves the character quitting their soulless corporate job and taking up a career in whatever field the creators consider to be good, honest work. In Allison’s case, however, the narrative suggests that opening yourself up to love, both platonic and romantic, can make your work better. This isn’t the kind of nebulous development that takes place in Frozen; love doesn’t just “thaw a frozen heart.” It causes Allison to take risks, to trust other people, to find value in herself irrespective of her brilliance. It helps her to make scientific advancements for the good of others instead of bragging rights and the attention of a neglectful father. Ultimately, it empowers her to save humanity.

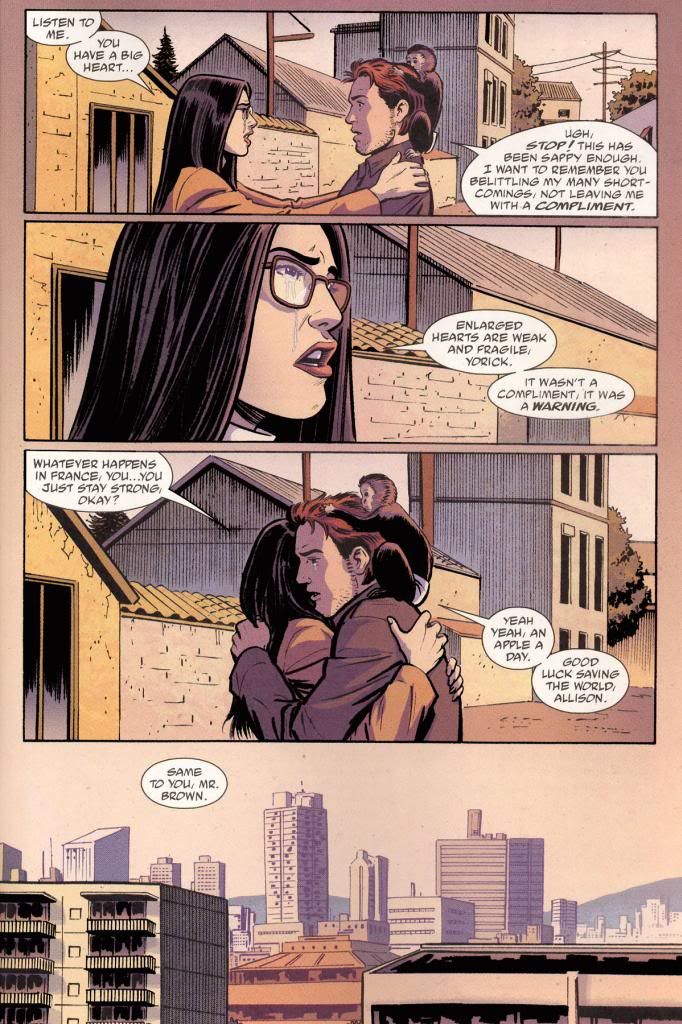

This is a particularly fascinating aspect of Y: The Last Man: Yorick may be the lead, but he’s not the hero. I’ll be discussing this in greater depth in the post about Hero Brown, Yorick’s conspicuously named sister, but it’s also highly relevant to any analysis of Dr. Mann. In Allison’s final scene, the last thing Yorick says to her is, “Good luck saving the world, Allison.” She wishes him the same, but it’s made clear in the final issue that she was vastly more successful. Before she died, Dr. Mann cloned females en masse and impregnated Rose with a viable clone of Yorick. Yorick ends up a relic of another world, trying and failing to find meaning in his survival. Yorick wallows in the existential angst of being the last man, while Allison ensures that there will be another.

Verdict: Actual strong female character