The Second Age of the Princess is upon us. However, with film titles like Tangled, Brave, and Frozen, you could be forgiven for not noticing. Disney is going through a bit of a strange period, in the sense that it wants to keep the girls and their billions, but it also wants to bring in boys. To do this, the company bought the iconic characters of Marvel, and, at the same time, made its fairy tale adaptations less recognizable. If we didn’t know better, we’d almost say that Disney is ashamed of its princesses.

Rapunzel

Less than a year after The Princess and the Frog,

Disney released another princess movie. And it would really like you to

know that it’s not like those OTHER princess movies, except that it

totally is.

In

Disney’s reimagining of the fairy tale, the former commoner, now Disney

princess Rapunzel is the magic-infused product of a union between a

king, a queen, and a life-saving sun flower. Eighteen years after she

was kidnapped by a witch, Rapunzel lives in a tower isolated from

everyone but her “mother,” Gothel. In this time, she has become a bit

unhinged. She is almost obsessively busy at all times; her “I Want” song

includes her actual dream as something of an afterthought, breaking up a

long list of her daily distractions. These distractions include

performing all aspects of floor cleaning and maintenance, doing laundry,

reading, painting, playing guitar, knitting, cooking, doing puzzles,

playing darts, baking, doing paper maché, dancing, playing chess, making

pottery, doing ventriloquism routines, making candles, stretching,

sketching, climb, sewing, and brushing her hair. It’s a wonder she has

any time in her schedule to pencil in some existential angst. She asks,

“When will my life begin?”

And,

for everyone familiar with the Disney princess library, we know that

the answer is “when the guy shows up.” The problem is that the guy has

already shown up, not merely introduced earlier, as in other princess

films, but actually telling the story. The film opens with a man, Flynn

Rider, telling us that this is the story of how he died, then amending

that assertion by saying that it’s not actually his story at all, but

Rapunzel’s. It’s fine to claim such a thing, but the fact that he

delivers the voice-over is reason enough to doubt this claim.

Another reason lies in the title of the film itself. Developed under the title Rapunzel, Tangled was renamed fairly late in the game. The lacklustre box office performance of The Princess and the Frog

led Disney to make a completely logical deduction: if a film does not

perform well, it is not because it was sidelined by sidekicks, didn’t

develop its villain enough, and had a problematic message, but rather

because it had “princess” in the title. Apparently, as Disney studio

executives claimed, the film was “prejudged by its title,” which failed

to draw in the desired demographic for princess movies: little boys. If

all of this sounds a bit ridiculous, that’s because it is. Floyd Norman,

a retired Disney animator who worked on Mulan,

said of the name change: "I'm still hoping that Disney will eventually

regain their sanity and return the title of their movie to what it

should be. I'm convinced they'll gain nothing from this except the

public seeing Disney as desperately trying to find an audience." It is

also a matter of Disney biting the hand that feeds it, raking in

billions of princess-generated dollars while trying to distance itself

from the very idea of princesses.

This may be why Rapunzel and Tangled

feel a bit more Dreamworks than Disney. Another departure from the

Disney brand is the protagonist who is not merely assisted by a magical

person, but is actually magical herself. The flower grown from a sunbeam

instils in Rapunzel’s hair magical powers: it is prehensile, possesses

the ability to heal and restore youth, glows, and grows

at a distressing speed. This appears to be the first instance of a

princess having legitimate superpowers, although they are

stereotypically feminine ones. There is nothing inherently wrong with

feminine forms of power; however, it is problematic that the hair’s

primary ability seems only to exist for the healing and restoration of

other people. In addition, the climactic moment of the film occurs when

Flynn chops off Rapunzel’s hair, preventing her from sacrificing her

future in order to save him, but also eliminating her powers. It’s tough

to support a film in which the climactic scene treats the loss of a

woman’s power as a net positive because she gets the guy at the end.

Although

Rapunzel’s dream of seeing the floating lights gives the film its

structure, it is her new dream that gives it its message. When Flynn

dies, he informs Rapunzel that she was his new dream and she says the

same of him. We hate Rapunzel’s first dream because, while focused,

seeing the lanterns is a day trip, not a life goal. We know that the

lanterns are an obvious stand-in for the world outside and that what

Rapunzel really wants is to see the wonders of the world outside her

tower, but that doesn’t make the temporary escape from a life of inanity

a better goal than actual escape. Also, Quasimodo did it first and

better, because he couldn’t just use his hair to climb down at any time.

The problem with her second dream of romantic love and a future with

Flynn Rider in his true identity as Eugene Fitzherbert is the

implications. Although Rapunzel is stuck in an abusive relationship with

her kidnapper “mother”, it is still troubling that the film’s message

is one of romantic love (of a day and a half) defeating familial bonds.

Even the restoration of Rapunzel’s biological family at the end doesn’t

really resolve this issue.

Finally,

we can’t discuss Rapunzel without addressing the frying pan. On the one

hand, Rapunzel’s chosen weapon is a lovely statement about the use of

traditionally domestic objects in new situations; like Rapunzel herself,

the frying pan finds a place outside the home. At the same time, it is

played for laughs every time it is used, by Rapunzel or anyone else.

When she hits Flynn in order to defend herself and her home, she is

taking down an invader and potentially proving that she can handle

herself in the world outside. This should be a defining moment for her,

and she obviously thinks it is, joyously exclaiming, “I’ve got a person

in my closet!” It is, however, once again made into a joke when she

celebrates by flourishing the pan and hits herself in the head. Mulan

may have fumbled with her sword, but she learned pretty quickly how to

use it. In contrast, Rapunzel’s weapon of choice and the things she

accomplishes with it are made out to be ridiculous, and the agency she

asserts in doing these things is dismissed with laughter. We are not

amused.

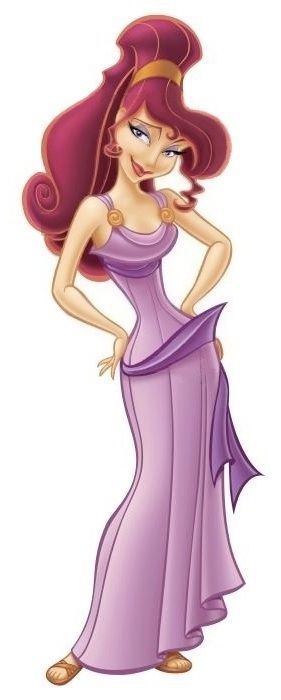

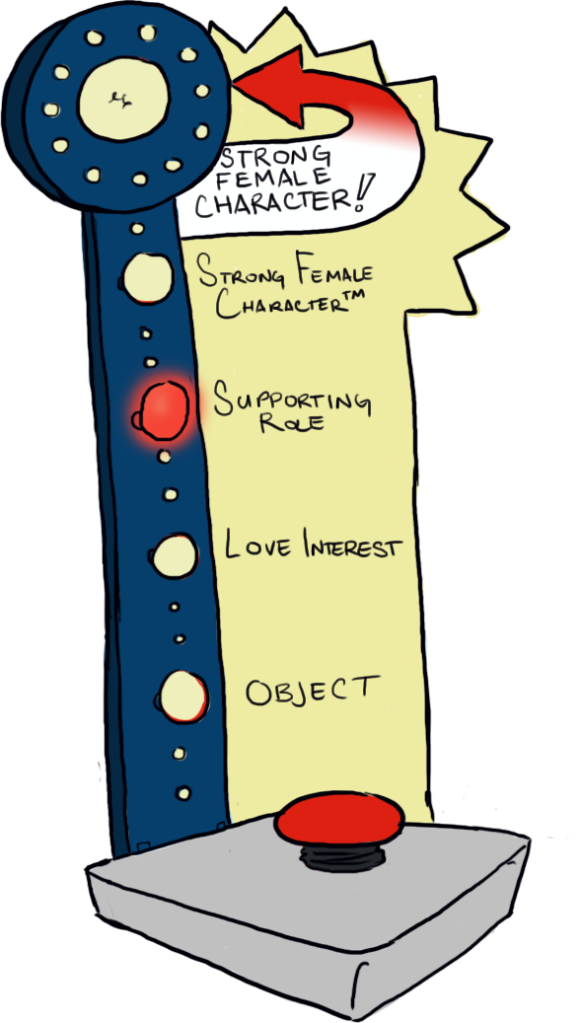

Verdict: Strong Female Character ™

Second Disclaimer: Technically Disney-Pixar, But Disney Seems On Track To Adopt Her As An Official Princess, So We’ll Be Treating Her That Way

Merida is, in many ways, Rapunzel’s polar opposite. Whereas Rapunzel is a Disney Princess by way of Dreamworks, Merida is both a subversion of, and tribute to, the women who came before her. She has the weaponry skills of Mulan, the athleticism of Pocahontas, the rebellious selfishness of Ariel, and a whole host of other qualities gleaned from her predecessors. (For more on this and a few other points we will bring up, see the brilliant “Just Another Princess Movie” by Lili Loofbourow.)

For all that she is derived from the other princesses, Merida is unabashedly herself. With a mane of hair that is itself basically a force of nature, she is stubborn, willful, and strong. She has that quality known as “mad swag,” with confident movements and a massive presence. It seems like a small thing, but she is shown eating on multiple occasions. Her usual snack is an apple from which, like Snow White, she takes only one bite. However, when she brings a platter of pastries out to the dinner table, her mother assumes that that is her meal, making it easy to infer that she does not have a small appetite. She lacks the prettiness and daintiness that tend to mark the princess line, portrayed even in promotional material with a sort of dorky, wide grin and a proud, open posture. When she’s angry or frustrated, she swings a sword around, taking chunks out of her bedposts and forcing people to give her a wide berth. Unlike her predecessors, she does not sing, so her “I Want” song takes the form of the soundtrack that accompanies her on her adventures. In this scene, with “Touch the Sky” in the background telling us about Merida’s yearning for freedom, Merida completes a difficult, oft-practiced archery exercise, gallops around on her Clydesdale, and climbs a rock face to drink from a waterfall. You know, just for the hell of it.

It is perhaps this behaviour, which draws no attention when it is a male character that is awesome at everything, that led Roger Ebert to declare Merida an “honorary boy.” What is refreshing about Merida, however, is that she is no way a boy, choosing to wear dresses and at no point expressing any interest in being anything but a girl. At the same time, she is being trained as a prince in the guise of a princess. Her father, Fergus, teaches her falconry, swordplay, and archery, while her mother, Elinor, teaches her public speaking, history, music, and embroidery, providing training to make Merida both commander-in-chief and lawmaker. When Merida tells the story of climbing the Crone’s Tooth to drink from the Fire Falls, Fergus observes that “only the ancient kings were brave enough to drink the fire.” Even with the threat of impending marriage hanging over her head, we know that Merida is going to be the one wearing the crown and calling the shots.

Indeed, the main conflict kicks off because Merida has her agency taken away. Immediately after Fergus suggests that Merida’s accomplishment makes her part of a group of kings, Elinor tells her that she will have to marry a man who will, we assume, become king instead. Merida, having been created for today’s audiences and therefore not overly taken with the idea of adhering to 10th Century social conventions, is livid. The day of the competition for her hand, which she has already rigged in her favour, she exploits a loophole and proclaims, “I’ll be shooting for my own hand!” She promptly follows through on this promise and beats her suitors soundly. Unfortunately, she’s basically started a war by humiliating her clan’s allies, and her mother understandably reams her out, so Merida turns her into a bear. This is one of the truly lovely aspects of the film: Merida shifts blame onto the witch, but she was the one who demanded a spell to change her fate. Her personal journey involves accepting the truth of her agency; she committed this horrible act, and she must set things right. She is, in this sense, her own antagonist.

Merida continues to distort gendered dichotomies as her story revolves around the typically masculine concept of fate. (Yes, we know that the existence of the legendary Fates and the convenient presence of three major women in this film link it to the feminine conceptualization of fate; however, the fact that it is treated as a kind of heroic destiny makes it an example of a generally masculine trope.) Her destiny, as assisted by the wisps, involves her maturation into a more thoughtful, less selfish person. This development is also directly linked to her diplomatic ability, suggesting that the realization of her destiny will allow her to become a better ruler. In order to achieve this destiny and save her mother, she must lock swords with her father and mend the tapestry with needle and thread, thereby employing both traditionally masculine and feminine tools. (We had planned to use an epic phallic symbolism joke here, but once we considered the context, our brains rebelled and rejected every joke out of sheer horror. Actual gray matter may have leaked out of our ears.)

Although our own sad attempts at humour may have melted our brains, it is the masterfully crafted, subversive message of this film that blew our minds. Brave is set in a world where everyone either is or claims to be stereotypically brave, but this is only part of the reason behind the title. Numerous critics saw the movie, expecting some rollicking adventure film starring a warrior princess who wrestles bears with her bare hands or something of the sort, and many viewers have claimed that the title has no relevance to the content of the film.

However, what they failed to notice is that punching bears in the face is not a pastime practiced by most of the audience members. This kind of bravery is not novel or useful. Merida’s true bravery lies in confronting her own mistakes and learning from them, in having the courage to play her part in keeping society afloat, and, honestly, in facing the fact that she’s a bit of an asshole and trying to be less of one. Ultimately, it is much less difficult to face a horde of enemies or climb a sheer rock face than it is to confront your own failings and actively seek to fix them. Merida is not perfect, but she is made stronger by her imperfections.

Also, she delivers her own damn voice-over.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

Anna (and Elsa)

The third in a list of films that have all spent years in development hell, Frozen is Disney’s next princess venture. The film, formerly known as The Snow Queen (see bitterness about the Rapunzel to Tangled

name change above to get our feelings about this shift), is slated to

come out in November 2013, and we want to look at it as the potential

future of the Disney princess brand. The following is all speculation

based on the information currently available about the film, and we will

have a follow-up review to address the differences between the film and

the hype when it is released.

The second released synopsis reads as follows: “When Anna is cursed by her estranged sister, the cold-hearted Snow Queen, Anna’s only hope of reversing the curse is to survive a perilous but thrilling journey across an icy and unforgiving landscape. Joined by a rugged, thrill-seeking outdoorsman, his one-antlered reindeer and a hapless snowman, Anna must race against time, conquer the elements and battle an army of menacing snowmen if she ever hopes to melt her frozen heart.”

Our first concern is the description of the characters. While the male lead, Kristoff, has an actual character description, we learn almost nothing about Anna or the Snow Queen. We don’t even learn the Snow Queen’s name, which is apparently Elsa. In addition, we have the ever-present male sidekicks, one of whom also gets more of a description than our protagonist. At least one person who has seen concept art, heard one of the songs, and knows more about the plot of the film, claims that it is a story about the two sisters. They also say that the sisters’ relationship will be significantly less adversarial than the synopsis suggests, which makes us wonder why Disney chose to release such a misleading description. Does pitting two women against each other really make people rush to buy tickets?

This person claims that “Elsa creates snowmen monsters to guard her castle of ice atop the mountain. However these hideous beasts get out of control and are going to attack the kingdom.” This is problematic for the simple reason that it makes this film one of a tremendous number that suggest that women can’t handle power. It is already bad enough that Elsa’s ability to control ice is framed as negative and apparently leads her to a self-imposed exile, but the fact that she can’t actually control the ice she can supposedly control is particularly galling. The film may give her the opportunity to reclaim this power as positive and learn how to wield it properly. We certainly hope so.

The final troubling aspect of that synopsis is this language about hearts. The Snow Queen is “cold-hearted,” which the OED defines as wanting in sensibility, cordiality, or natural affection; unfeeling; unkind. We appreciate the fact that Merida’s a bit of an asshole, so we would be ecstatic about a positively portrayed female character who isn’t the embodiment of sunshine and rainbows, and doesn’t go out of her way to please others. Even Anna must try to “melt her [own] frozen heart,” which is implied to be part of the curse laid on her by her sister. The women in this film are portrayed as defined by their hearts, not their brains or anything else, so we would not be at all surprised if Anna’s heart is melted by that “rugged, thrill-seeking outdoorsman.” We hope that it will be reversed through sisterly affection, but we’ve now watched nine of these things end in magical heterosexual romance, and one end in implied romance confirmed by the sequel, so we’re not holding out hope.

We would love to have our cynicism proven unfounded, if only because we would like Merida, not Rapunzel, to be the originator of the next set of Disney princesses.

Conclusion

How do you summarize seventy-five years of princesses? What does being a princess mean?

For Snow White and Aurora, it seems to be a sign of their worth, as the fairies tell Aurora when they give her “this one last gift … the symbol of thy royalty: a crown to wear in grace and beauty, as is thy right and royal duty.”

For Cinderella, Belle, Ariel, and Tiana, it is part of their reward. There is no indication that any of these women will have actual power, as Cinderella’s father-in-law just wants her to have babies, Belle and Ariel marry princes who don’t seem to be involved in any actual ruling, and Tiana’s life stays pretty much as it would have been if Naveen were an ordinary guy. Of course, one day Naveen will be the king of Maldonia, and they will probably have to live there and leave the restaurant; becoming a princess actually means that Tiana will lose her dream. Yay?

For Jasmine, it is being governed by stupid laws, but also, when she is queen, having the power to fire people. Aladdin is explicitly identified as the real future ruler.

For Pocahontas, it is setting an example and sacrificing an apparently epic love.

For Mulan, it’s not actually an issue because, in a way, she doesn’t even go here. She’s also too busy being a badass to care.

For Rapunzel, it is the restoration of her identity and her family.

For Merida, it is a job: intense training for the day when she takes power as the commander-in-chief, head diplomat and lawgiver of a precariously balanced kingdom.

Being a Disney princess means that you will be loved by millions of children, who will one day introduce you to their own children (or, in our case, nephews). These films are rife with problematic elements, but there is still something to be said for many of these characters.

I recently bought a set of Disney princess board books for my nephew (and, I must admit, for the look on my brother’s face). Entitled “I Can Be a Princess,” the set offers twelve lessons: be yourself (Mulan), be adventurous (Rapunzel), be fair to others (Belle), believe (Cinderella), be curious (Ariel), be thankful (Aurora), be determined (Tiana), be polite (Snow White), be kind to animals (Cinderella), be friendly (Rapunzel), be independent (Jasmine), and be brave (Belle, but it’s okay, because I bought a Brave book as well). It’s less about being royal than about being a decent human being, and we think that’s an important lesson for anyone to learn. Even boys.