(Note: This post will focus primarily on the theatrical release of Pacific Rim. There is a significant amount of supplementary material available, and I will be discussing some of it, but I think that it’s important to address the world and characters as portrayed on the screen. Significantly fewer people are going to read the prequel comic, the novelization, Guillermo del Toro’s interviews, and Travis Beacham’s blog. And now, without further ado, the first entry in Request Month: 2 Fast 2 Furious.)

When I first saw the trailer for Pacific Rim, I, like many others, thought it looked like the love child of Transformers, Godzilla, and a particularly colourful neon glow stick: the product of a summer Hollywood blockbuster breeding program. Despite the involvement of Guillermo del Toro and Idris Elba, I had no intention of seeing the film. But that all changed when the Fire Nation attacked.

In this case it wasn’t Azula and her ilk who invaded my corner of the Internet, but another Japanese woman associated with the colour blue. Mako Mori was suddenly everywhere, and I knew immediately that I would not only be seeing Pacific Rim but writing about it.

Set in the near future, Pacific Rim takes place in a world where gargantuan monsters called Kaiju emerge from an interdimensional portal under the ocean, known as the Breach, to wreak havoc on a global scale. When traditional weapons prove ineffective against the Kaiju threat, the nations of the world come together to find another solution. That solution is the Jaeger, a massive, nuclear-powered Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robot, piloted by a two-person team whose minds are linked through a neural handshake. One such team is comprised of the Becket brothers, Raleigh and Yancy, the latter of whom is killed during a mission. Raleigh is left without a co-pilot or a Jaeger, and he leaves the program. As the frequency of Kaiju attacks increases, more and more Jaegers fall. Governments turn to ostensibly Kaiju-proof walls to protect their coasts, but these prove useless. With the end of human civilization looming, it is up to Marshal Stacker Pentecost and the pilots of the world’s last four Jaegers to destroy the Kaiju and seal the Breach.

Mako Mori’s strong female character credentials are established in her first few minutes of screentime. She is introduced as “one of [Pentecost’s] brightest.” While Raleigh, the white male protagonist, has only just learned about the plan to seal the Breach, Mako has already played a major part in the mission. She oversaw the restoration and upgrade of the Becket brothers’ Jaeger, Gipsy Danger, and she compiled the list of candidates for the co-pilot position. She has an intimate understanding of the inner workings of both the machines and their pilots, whose number she wishes to join. To that end, she has completed fifty-one simulator missions with fifty-one kills: a perfect record. To put this in some perspective, the prequel comic compares piloting a Jaeger to “trying to solve a Rubix Cube in the middle of a boxing match.” Doing that successfully a hundred percent of the time is astounding.

It is this level of expertise that qualifies her to judge Raleigh’s own record. She calls him out on all the usual traits of the white, male hero: “I think you’re unpredictable. You have a habit of deviating from standard combat techniques, you take risks that injure yourself and your crew. I don’t think you’re the right man for this mission.” Of course, we know that he will prove to be the perfect person for the mission, but it’s still notable that Mako is willing to point out that the qualities that make him a good Hollywood hero also make him a potential liability in the field. It is equally notable that Raleigh himself respects her opinion, even though she’s basically telling him that she thinks his redemption arc is going to get people killed. She is intelligent, competent, and unafraid to do and say what she thinks is right.

Because Pacific Rim was marketed as a Hollywood blockbuster, we think we know how this will turn out: Raleigh will engage in reckless behaviour that saves the world and proves Mako wrong. She will exist only to serve his storyline, likely as his love interest and the prize he earns for said reckless behaviour. At best, she will become his sidekick. We need look no further than The Wolverine for examples of both possible paths, conveniently -- and tellingly -- also portrayed by Japanese women whose only function is supporting the real hero, a white man. We’ve seen it before, and we think we’ll see it again in Pacific Rim.

Then the film disappoints our expectations in the least disappointing way possible: Mako becomes the deuteragonist. Instead of serving Raleigh’s arc, she is given a separate, complementary storyline; boiled down to its bare essence, he is the has-been, she is the rookie, and they both need Gipsy Danger’s help to exorcise their demons.

In order to gain entry to the Jaeger, Mako must demonstrate her compatibility with Raleigh, both mental and physical. To prove the latter, she must fight Raleigh using a specialized form of martial arts termed “Jaeger Bushido.” Pentecost is initially reluctant to let her try out, but after Mako tells Raleigh that he’s not trying hard enough and Raleigh challenges her to a match, he concedes. Raleigh tells her that he’s “not gonna dial down [his] moves,” and Mako assures him, “Neither will I.” What follows is a battle between equals, as they match each other point for point, until Mako has Raleigh on the floor.

What has thus far prevented Mako from piloting a Jaeger is Stacker Pentecost. In a Drift-produced flashback, we learn that Mako survived a Kaiju attack in Tokyo when she was a child. She witnessed the battle between Coyote Tango and Onibaba, as the Jaeger, piloted by Pentecost, destroyed the Kaiju that killed her parents. Afterwards, Pentecost adopted her, trained her, and raised her in the Shatterdomes; he became her superior officer, her sensei, and her adoptive father. When she leaves the combat arena, certain that she will be denied the position of co-pilot, Raleigh tries to get her to fight back, claiming, “You don’t have to just obey him.” “It’s not obedience,” she responds. “It’s respect.”

The film does a lot of subversive work using these two relationship dynamics. Mako’s relationship with Pentecost revolves around respect, but it is important to note that this respect goes both ways. While Mako obeys Pentecost’s orders, she doesn’t do it out of hero worship. She knows that he is a good leader, and she does what he asks not just because he asks it, but because she trusts that he has good reason to ask it. This doesn’t mean that she stays quiet when she takes issue with his orders, confronting him in person and (in the novelization) going so far as to “strenuously object” with his rulings in official documents. He, in turn, shows respect for her culture, her personal space, and her accomplishments. Later, when Pentecost decides to pilot a Jaeger, knowing that it is a suicide mission, he asks Mako to protect him. When he dies, she calls him “sensei” one last time. Despite the power imbalance, their mutual respect makes them equals.

The film’s equalizing project is particularly subversive in the case of the relationship between Mako and Raleigh. The whole concept of the two-pilot system and the neural handshake is compatibility; your ideal partner is the person who drives you to excel, and who then matches you in excellence. The neural handshake enables two people to become one incredibly powerful entity. Making Mako, an Asian woman, the perfect match for the white, male hero, suggests that she is his equal. In the summer blockbuster, where no one is more important than the white, male hero, this is a big deal.

In light of Hollywood’s long history of portraying Asian women as subservient, submissive, sexualized objects, Mako’s treatment is especially subversive. In addition to the equal status suggested by her Drift compatibility with Raleigh, the film supports her power and importance through more subtle devices. She is always fully dressed; there are no Star Trek-style underwear shots to appease the male gaze. In fact, there is a scene in which she watches Raleigh removing his shirt through a doorway and then through the peephole in her own door, explicitly assuming the gaze herself. Still, Raleigh’s gaze does play a role in Mako’s treatment, in the sense that he gazes at her like she’s the greatest person in the world. He fights on her behalf, always in an attempt to ensure that others acknowledge her brilliance and treat her with the kind of respect that he believes she deserves. The film essentially uses the audience’s identification with its white, male hero to convince them that Mako is the best character in the movie.

What I find particularly impressive is the film’s ability to balance Mako’s characterization; while she is intelligent and competent, she is also a rookie, and rookies make mistakes. Mako’s major error occurs during the first neural handshake test. When she and Raleigh link minds, he gets distracted by memories of his brother; this, in turn, causes Mako to “chase the rabbit” into the Drift and relive her own traumatic experience. While she inhabits her own terrified eleven-year-old mind, she subconsciously charges up Gipsy Danger’s plasma cannon, putting everyone and everything in the Shatterdome in danger. Although they manage to power down the Jaeger and avoid disaster, Mako is deemed unfit as a pilot. By grounding her, Pentecost prevents her from taking advantage of what may be her last opportunity to avenge her family.

Earlier, when Mako confronted Pentecost about taking part in the co-pilot trials, he informed her that “vengeance is like an open wound. You cannot take that level of emotion into the Drift.” Ironically, Mako’s single-minded mission to get revenge on the Kaiju stands in the way of her ability to use the one weapon with which she can take this revenge. While some people have criticized this scene and the final showdown -- in which, at the last moment, Mako’s oxygen feed is damaged, she passes out, and Raleigh saves her by jettisoning her in an escape pod -- I think that there are sound reasons for both moments of weakness.

The former is basically a matter of putting Bruce Wayne back in that alley with Joe Chill, and giving eight-year-old Bruce a gun that will stop him from ever having a reason to become Batman. In this case, however, Joe Chill is a 2500-tonne, city-destroying monster, and the gun responds to thought commands. Mako gets distracted, but, given the enormity of her trauma, it would be unrealistic if she didn’t. In some ways, this moment is actually a subversive triumph: Mako’s emotion and subjectivity fly in the face of the emotionless, inscrutable Asian stereotype. Furthermore, it’s a woman who, while experiencing a moment of apparent powerlessness, finds the power to fight back. It’s the wrong time and place, sure, but it’s a little inspiring just the same.

“Even though my personal preference would have been for Mako and Raleigh to do the final moment together, I will forever appreciate that we got a scene where a white man thought an Asian woman’s life was worth more than his and actually made sure she would survive for sure while he went on a suicide run where survival was uncertain, but unlikely, even if he did survive in the end.

Which is also why it annoys me when I see people in Mako’s tag say that it would have been more ‘feminist’ (and I guess ‘anti-racist’, though not like these people every acknowledge that Mako isn’t white) if she had saved him and ejected him from the pod and even died herself, because do you know how damn often in white man/Asian woman pairings especially, the Asian woman is supposed to nobly die for the white man while he moves on? And the whole ‘stoic Asian who dies so the white man can live as he accepts his death with honour~’ crap.”

It’s important to remember that every race is portrayed in mainstream media using a different set of stereotypes and tropes. Just because an Asian female character doesn’t conform to the ideal that has been established with white women in mind doesn’t mean that the Asian woman’s portrayal is inherently unfeminist or regressive. In many ways, not adhering to the criteria of a Strong Female Character is actually a testament to Mako’s strength as a character.

I defy anyone to call Mako weak after seeing her first outing in a Jaeger. When Cherno Alpha and Crimson Typhoon are destroyed and Striker Eureka is paralyzed during the first double event, Mako and Raleigh get their chance to redeem themselves following their disastrous test run. Not only do they kill both Kaiju, they vanquish the second one mid-air while it’s flying Gipsy Danger into the stratosphere. While Raleigh exclaims that they’re out of options, Mako deploys one of her personal additions: a chain sword, designed to honour her sword maker father. She slices the Kaiju in half, claiming the kill for her family, thereby satisfying her need for vengeance and completing her character arc. Although she goes on to play a major role in the final battle, this is the climax of her story. She has redeemed herself, avenged her family, and looked mighty cool doing it.

The biggest problem with Mako Mori is not a problem with her, but with her environment. While Pacific Rim generally does a good job of representing a global conflict that actually involves the entire world, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that the “entire world” seems to be just as dude-heavy as it is in any other blockbuster. Of the principal characters, only two are women: Mako and the Russian pilot of Cherno Alpha, Sasha Kaidonovsky, who gets a few lines, a little screentime, and an unpleasant death. As in every modern discussion of the feminist value of a given film, critics have highlighted the gender disparity in Pacific Rim through the use of the Bechdel test. It fails; Mako interacts more with the Hansens’ bulldog, Max, than she does with her fellow female pilot.

Regardless, it is difficult to dismiss a film as unfeminist when it features a character like Mako Mori. To that end, Tumblr user Chaila has proposed the Mako Mori test, which is passed if the movie has “a) at least one female character; b) who gets her own narrative arc; c) that is not about supporting a man’s story.” Chaila suggests that it be used alongside the Bechdel test; while passing either test (or both) does not necessarily make the film feminist, it does indicate that the female characters are being treated at least a little like actual people.

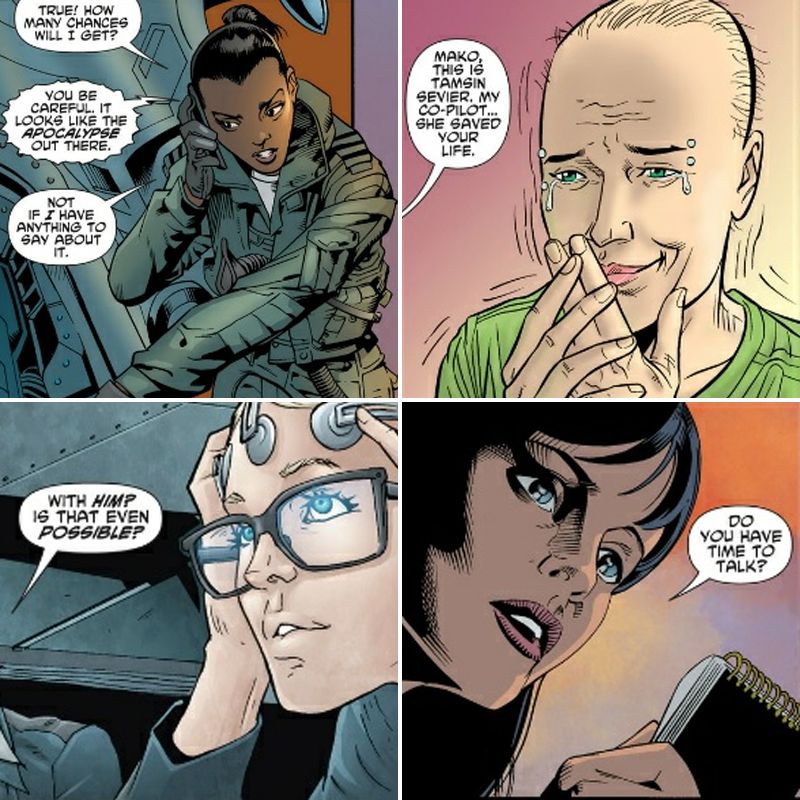

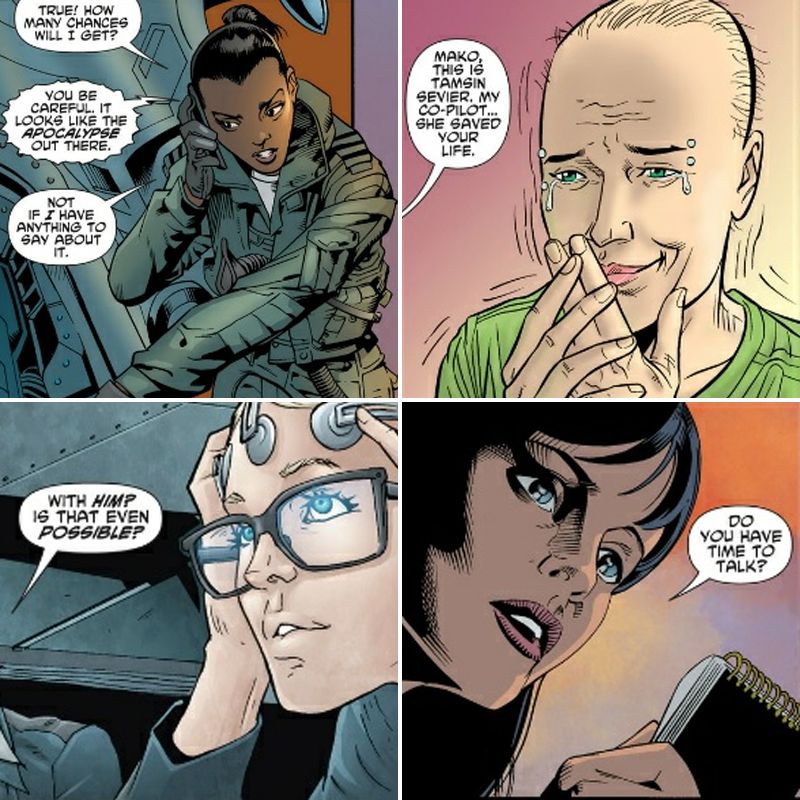

Personally, what bothers me is that the world of Pacific Rim does have a number of compelling women; they just didn’t make it onto the silver screen. The prequel comic, Pacific Rim: Tales from Year Zero, written by Travis Beacham, features four women who easily could have been included in some way, and whose inclusion would have improved the film. The first is Luna Pentecost, Stacker’s sister and a fighter pilot with the RAF. She volunteered to take on the first Kaiju when it struck San Francisco, ostensibly to repay the Americans for their help during the Blitz. Stacker points out that she really just wants to slay a dragon. She dies in the battle, but her influence is apparent in the way that she inspires Stacker. The second is her friend and fellow pilot, Tamsin Sevier, who went on to join the Jaeger program as Stacker’s co-pilot. She also gave her life for the cause, dying of cancer from exposure to the Jaeger’s nuclear core. The third is Naomi Sokolov, a journalist and former “Jaeger-fly”. As a teenager, she was attracted to the Jaeger pilots’ celebrity; as an adult, she turns an assigned puff piece into an examination of the political reasons for the shift from offensive weapons to defensive coastal walls. She goes from being drawn to the glamour of the celebrity heroes to understanding and advocating for the program itself.

Finally, there is Dr. Caitlin Lightcap, the inventor of the Pons, the technology that allows for the neural link between two pilots and their Jaeger. We meet Dr. Lightcap, one of the world’s leading experts in brain-machine interfaces, when a deep depression has interrupted her work at DARPA. While her former professor creates the machines, she makes them work. She is also responsible for discovering the need for two minds to share the neural load, having saved one of the test pilots by linking up to the Pons. She then goes on to join this test pilot in the first Jaeger prototype and log the first Kaiju kill without the aid of nuclear weapons. Describing this event, her scientific partner says, “I know one thing for sure: it felt pain. And half of what hurt it -- maybe more -- was that mouse of a girl from Pittsburgh. The message was clear -- we are far bigger than we look.” The fact that this woman doesn’t even get a mention in the movie is an absolute travesty.

Still, given time constraints, I can understand why these specific characters didn’t make the cut. That doesn’t mean that others couldn’t have been created. In fact, there is nothing in their characterization that would prevent Stacker Pentecost, Herc and Chuck Hansen, or Hermann Gottlieb and Newt Geiszler from being women (or, in the case of those last four characters, people of colour). In a more perfect world, we might even see Raleigh Becket himself replaced by a female version.

Unfortunately, it isn’t perfect. In using the trappings of the blockbuster, Pacific Rim perpetuates some of its more dubious traditions. (If I never see another film in which the only person who can save the world is a white, cisgender, straight dude, it will be too soon.) I like to think of it in terms of an Animorphs cover: the goal is to turn into a wolf, but the werewolf-like creature in the middle is still pretty cool.

Verdict: Actual strong female character