“Any delusions I once had about me being the protagonist of some predestined epic quest have gone the way of boy bands.” So says the last man on Earth, halfway through an epic quest of which he is certainly the protagonist. What Yorick is doing, however, is confusing the protagonist for the hero, which is what he really wants to be. In his head, he’s a dashing space captain, a barbarian warrior, and a slick noir detective: a hyper-masculine ideal who drives the plot and gets the girl. In reality, he’s surrounded by women who arguably have far better claim to the title of “hero.”

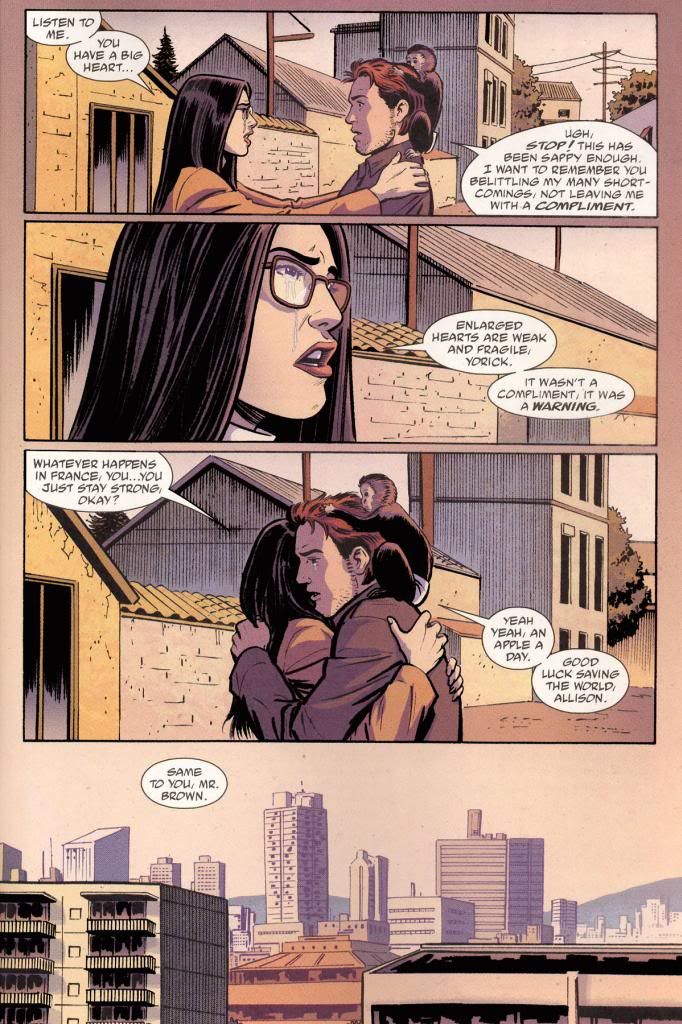

There’s Dr. Allison Mann, who solves the main problem of the series by restoring men to the planet. In fact, the climax of the gendercide plot revolves entirely around her and her relationships, while Yorick remains strapped to a hospital bed, unable even to understand most of what’s going on, let alone do anything to stop it. In the pivotal moment, he’s little more than a damsel in distress, rescued one more time by one of two women who have been saving his life for five years. There’s Agent 355, the bodyguard responsible for protecting Yorick, who is again figured in a role usually occupied by a woman. While he struggles with the possibility that he may not be the hero of the story, she busies herself with the actual heroics, all while trying to resist the corrupting influence of the violence that comes with survival in a dystopian world.

And then, of course, there’s the real reason why Yorick can never be the hero in his own story: the position was filled before he was born.

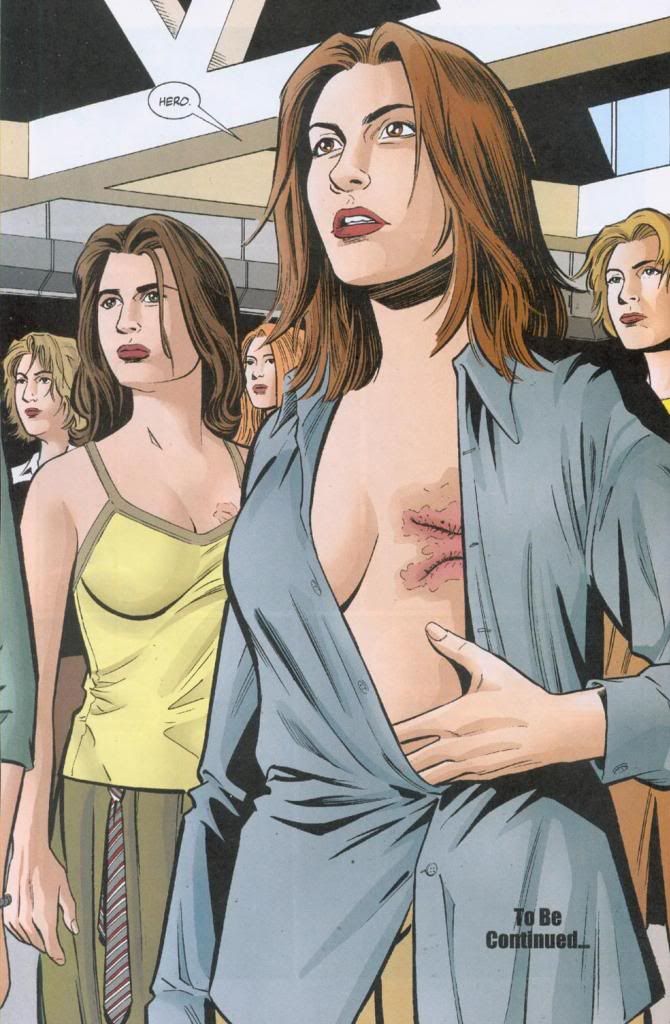

Hero Brown

Like Yorick, his older sister, Hero, is named after an obscure Shakespearean character: Beatrice’s sweet, spineless cousin from Much Ado About Nothing. The irony of her brother’s name, which comes from a man who dies before everyone else, instead of after, is echoed in her own. While her namesake swoons in the face of accusations of premarital sex, Hero Brown is introduced having sex in an ambulance while on duty. Still, as Yorick observes, “In a weird way, Hero and I sort of grew into our names. She got a gig as an EMT… I became a worthless joker.” For Hero, the Shakespearean connection, while amusingly ironic, is less relevant than the modern connotation.

Hero is Yorick’s most obvious foil. They look incredibly similar, and they both entertain, at one point or another, aspirations of becoming a writer. Most importantly, however, they both embark on a quest; while the brother has the designation of protagonist, it is the sister who goes on the hero’s journey.

According to The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell, the hero’s journey -- also known as the monomyth -- is the journey taken by the archetypal hero in mythology. This hero is usually male, and Campbell later argued that this was because “all of the great mythologies and much of the mythic story-telling of the world are from the male point of view. When I was writing The Hero with a Thousand Faces and wanted to bring female heroes in, I had to go to the fairy tales. These were told by women to children, you know, and you get a different perspective. It was the men who got involved in spinning most of the great myths. The women were too busy; they had too damn much to do to sit around thinking about stories.” There is… a lot to dissect in that comment, but what is most relevant to this analysis is Campbell’s identification of the limited narrative space that exists for heroic women. You don’t have to look much further than the Valentine’s card displays to see the difference between boys, who learn that they can be monsters and pirates and cars and superheroes, and girls, who are told that they can only be fairies and princesses. With her arc, Hero pretty much punches that gender division in the face.

The hero’s journey is split into three parts: Departure, Initiation, and Return, and it begins with the call to adventure. For Hero, that comes just after the plague strikes. She has just watched the man she loves die in her arms when a fellow EMT tells her that they have to help the living. Hero refuses, saying, “No. They can help themselves.” She then spends several months journeying from Boston to Washington, D.C., battling starvation as she treks across a post-apocalyptic landscape in order to find the last of her family.

Along the way, she runs into what Campbell terms “supernatural aid,” in this case the leader of the Amazons. The Amazons are a group of women who said good riddance to the end of mankind and ushered in the new matriarchy by blowing up all the sperm banks. They’re ultra-violent, man-hating straw women the likes of which only Fox News could dream up, though the narrative humanizes them by showing us Hero’s rise through the ranks. She is recruited by the leader, Victoria, when she sees a starving, almost feral Hero slice an Amazon’s face open with a tin can. Victoria rewards her with food for this desperate act and, when Hero tells her she’s looking for her mother, Victoria replies, “And found her you have.”

In the aptly named flashback issue, “Hero’s Journey,” we learn that Hero is particularly susceptible to the controlling influence of others. Before the plague, she was involved with “this constant parade of losers and… quasi-abusive scumbags” as she searched for the love and validation that she felt was missing from her father. Just when she thought she had found someone who truly appreciated her, a global extinction event took him away. Many fictional women share Hero’s tendency to trade agency for validation; the difference here is that the narrative overtly condemns this trait, instead of glorifying it as is the case in many a YA romance.

Accordingly, while Victoria serves as Hero’s mentor, protecting her and teaching her how to survive in the new world, she does so as a corrupting influence. She forces Hero to kill an innocent woman to prove her loyalty, and this murder has a profound psychological effect, triggering Hero’s long battle with psychosis. This could be read as a rather unpleasant version of Campbell’s “crossing of the first threshold” into the world of adventure. The next time we see her, Hero muses aloud that “it is so easy to kill someone. Easier than doing laundry. It… It even smells like laundry. I’ve done it. Have you done it? Killing, I mean, not laundry. Heh.” The effects of her psychosis only worsen after she witnesses Victoria’s death and kills the person responsible. By this point she is also suicidal, asking Yorick to kill her: “All you have to do is make a fist. The bullet does the hitting for you.”

After this bloody showdown, Hero goes into the “belly of the whale,” otherwise known as the prison at Marrisville. According to Campbell, “this popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation… Instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again.” This is precisely what happens to Hero, who spends her time in prison being deprogrammed. When she emerges, she is ready to continue her journey down the “road of trials.”

This is the point where Hero’s story becomes even more subversive, as she dons the trappings of Hollywood’s masculine heroism. When we see her next, she’s wearing a sort of modern cowboy outfit, complete with hat and six-shooter. Having left the prison some time earlier, she’s on a mission to save Yorick from Agent 355, whom their mother now believes to be a shady character. On her way through Kansas, she questions the owner of a brothel, who assures her that they operate inside the law. “I don’t,” Hero replies, every inch the cool Western lead. When she finally catches up to Yorick, she shoots and shatters a sword, only slightly undermining this feat of sharp shooting by pointing out that she was aiming for the attacker’s face. When he asks her if she plans to kill herself, she states, “I’d rather try to make up for some of the horrors I inflicted on the world before I off myself,” framing her journey as a road to redemption.

This stage of her arc is integral to Hero’s development, representing both her reconciliation with Yorick and her final rejection of Victoria. The former is important for mostly technical reasons; while she’s still perceived as an antagonist, it’s basically impossible to make Hero a hero. The latter is the most difficult trial on a road full of them. Even after her deprogramming, Hero hears Victoria’s voice in her head and sees her in delusions. On these occasions, Victoria urges her to kill Yorick and destroy every chance of restoring men to the planet. However, when she has the perfect opportunity to do just that, she chooses instead to resist. We see her in her own mind, still agonizing over one of the women she killed. Victoria urges her to kill both Yorick and Allison, and when she recites the reasons why the men deserved to die, Hero calmly tells her that she’s heard all of that before. Victoria then resorts to reminding Hero of the sexual abuse she suffered at her grandfather’s hands. Hero assures her that she remembers, but that she has moved on… then she stabs Victoria through the eye with the arrow Hero used to kill Victoria’s murderer. She turns the violence that Victoria instilled in her back on Victoria in order to rid herself of these same violent urges. In this moment, she also vanquishes the last controlling influence in her life, earning the freedom to live on her own terms.

The next stage of her journey along the road of trials begins with a letter that Yorick asks her to deliver to Other Beth, a woman he met on his own journey. When Hero finds her, Beth is heavily pregnant with Yorick’s child; by the end of the issue, Hero offers to take her along with her, telling Beth that she can provide medical help. Although Beth doesn’t let Hero know, it turns out that the letter Yorick sent asked her to be a friend to Hero. As they travel back across the United States, Hero and Other Beth pick up three more companions: Russian secret agent Natalya Zamyatin, astronaut Ciba Weber, and Ciba’s infant son, Vladimir Jr., the first boy born post-gendercide. Despite Natalya’s superior training, it is Hero who leads the group as they make their way across the Atlantic Ocean to return Vlad to his father’s homeland. Her task is incredibly difficult and its success equally impressive; while Yorick can disguise himself as a woman, there’s not much anyone can do to hide two babies whose existence should be impossible.

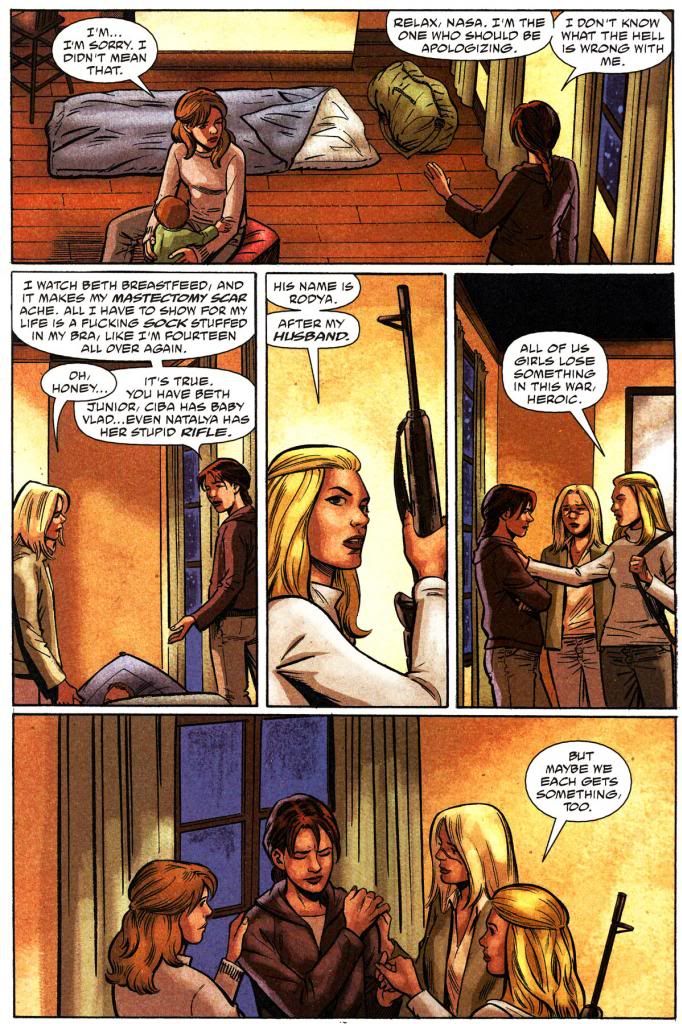

A hero usually completes his journey with a prize to keep and new knowledge to share when he arrives home, and Hero is no exception. Near the end of the journey, Hero and her friends are holed up in Paris, trying to find Yorick. Frustrated, Hero laments her solitary status: “I watch Beth breastfeed, and it makes my mastectomy scar ache. All I have to show for my life is a fucking sock stuffed in my bra, like I’m fourteen all over again.” She sees their treasures as symbols of accomplishment: motherhood and romantic love, represented respectively by the two children and Natalya’s rifle, named for her late husband. From her perspective, her quest is over and she has nothing to show for it. Natalya rejects this conclusion, telling Hero that she’s gained three friends.

This is a powerful idea. While a hero usually has to return with a princess, a golden fleece, a magical elixir, or, in this case, a lost brother, Hero’s reward is female friendship. Admittedly, due to Hero being a supporting character in the larger story, we don’t get to see her nurture these friendships. Still, the narrative’s explicit acknowledgement of the importance of friendship between women -- both in Hero’s relationships and the central bond between Allison and 355 -- is heartening. It’s also interesting, when you consider it as the endpoint of Hero’s arc. She begins as a woman dependent on the approval of men, and she transfers this dependency to Victoria following the gendercide. After her stint in prison, she comes to rely on herself, remaking herself into the very model of the lone cowboy. Finally, she becomes someone on whom other people can rely, who will cross the globe in aid of a friend. As the world begins to rebuild itself, she becomes what she was always meant to be: a Hero in word and deed as well as name.

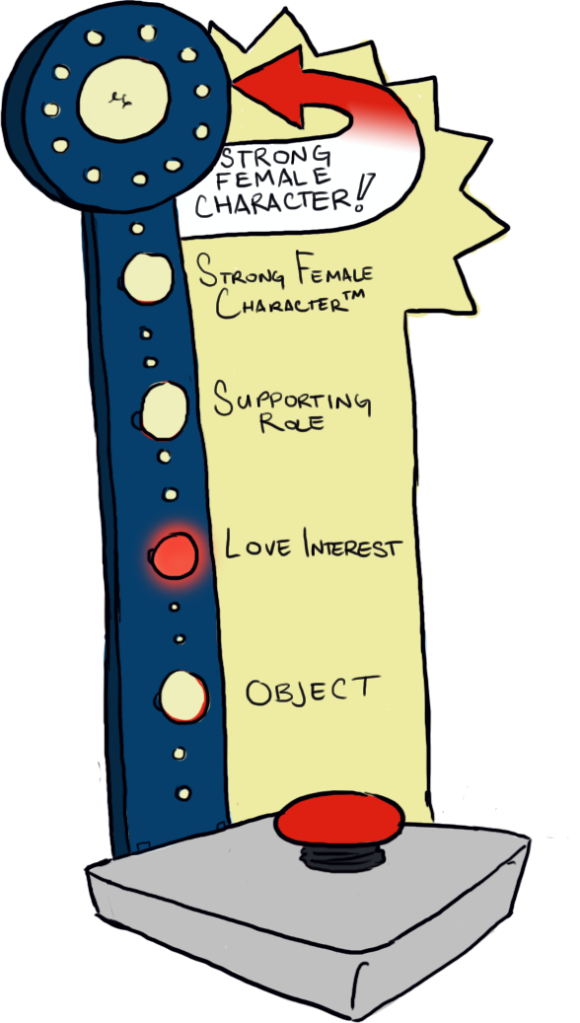

Verdict: Between Strong Female Character™ and actual strong female character, due to the fact that she spends most of her time as the hero of the C-plot

Beth Deville

Beth Deville is simultaneously the most important and least personally influential woman in Y: The Last Man. Finding her is Yorick’s primary goal; unfortunately, this means that she spends a large part of the series literally floating on an island far away from the main plot. Her existence drives the action, but her absence is required to make that happen.

Beth’s story is about what happens when a person is turned into a MacGuffin against their will. We are introduced to her through a conversation with Yorick, during which he laments the state of his life and she acts as the perfect supportive girlfriend, albeit one who is halfway around the world. Just as he’s gearing up to propose to her, she interrupts him to say something important; unfortunately, their conversation is cut off, her comment left unspoken and his proposal unanswered. This is how we see their relationship for most of the series: Yorick projecting his feelings and hopes into the silence with Beth unable to respond.

When Yorick decides to go from New York to Australia, he frames his search for Beth as a quest, making her the quest object. He also assumes that she was going to say yes to his proposal, further denying her subjectivity and agency. Later in the series, we learn that many of the things that Yorick appreciated about Beth were reflections of his own interests; they hate the same things and enjoy the same pop culture, and Beth is willing to wear a Hallowe’en costume that caters to Yorick’s fantasies. One of the lessons that he has to learn over the course of the series is that a woman is not his soulmate simply because they like the same media. To my mind, this speaks volumes about the depth of his relationship with Beth.

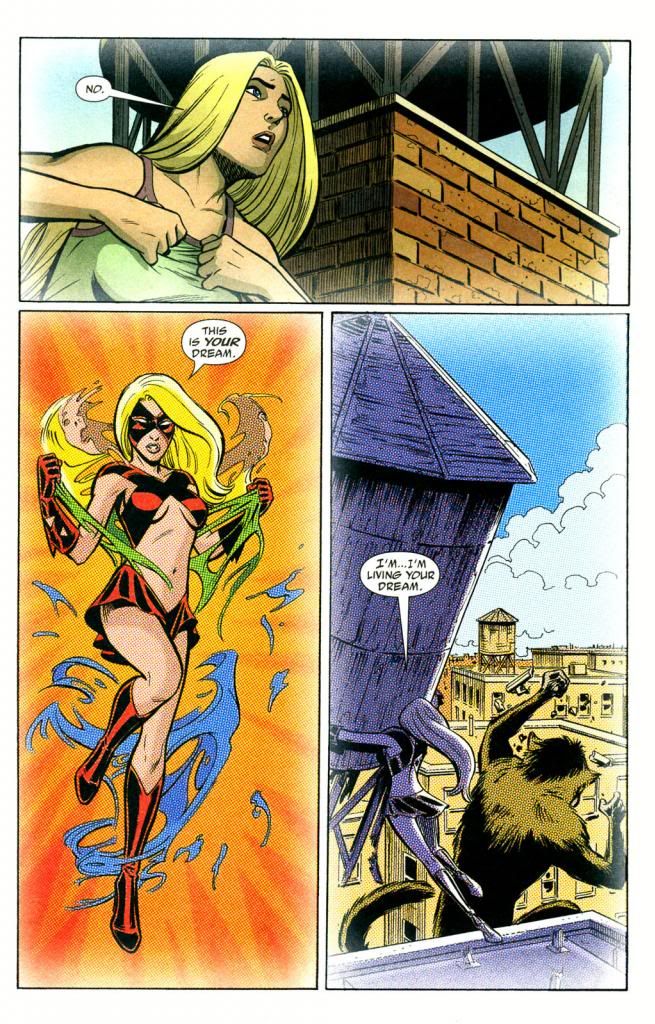

In light of this, it’s especially troubling that Beth spends most of her panel time as a figment of Yorick’s imagination; she is, quite literally, the girl of his dreams. In these dreams he is invariably the hero, casting himself in a number of Hollywood action roles and forcing his imaginary Beth to portray a host of generic love interests, all of whom are sexy and passive. In these dreams, Beth usually comes to some kind of physical harm and warns Yorick not to look for her. The crucial shift in this pattern occurs when we are given access to Beth’s dreamscape. Her memories and thoughts revolve around Yorick, and the vision culminates in a scene in which Beth turns into a superhero and saves Yorick from a giant capuchin monkey. Despite her central role, she realizes that this is not her dream but Yorick’s, and this connection allows her to realize that he is still alive.

This issue complicates Beth’s role as an object. Taking this new information, she travels to France in her own quest, for which Yorick is the prize. What makes her treatment subversive is the fact that Beth (and the narrative itself) calls attention to it. When she saves dream Yorick, she says, “No. This is your dream. I’m… I’m living your dream.” She shows us that Yorick has been projecting his own thoughts and desires onto her, and his dreams now replace her own. In this moment, we understand that what we have seen up to this point is Beth as Yorick sees her, not as she truly is. While he imagines her as a damsel in distress that he has to save, she makes herself the questing knight. The narrative builds on this with its follow-up to that first conversation and the interrupted proposal. After they are reunited, we learn that Beth was going to break up with Yorick during this conversation. Her life was going somewhere while his had hit a wall, and no matter how much she loved him, she wasn’t willing to let him hold her back. As she puts it, “I had a whole world to explore and you… you didn’t.” Seeing that he has undergone some serious personal growth, she is now able to see a future for them.

Unfortunately, while Beth does get some opportunity to contest her objectification, the narrative still isn’t terribly interested in her as a person. As soon as she decides to go to Paris, she promptly disappears from the story, not to be seen or heard from for upwards of a year (in both comic and real time). She gets to stick around a little longer after her confession, but most of her panel time is spent as bait intended to lure Yorick into a trap. After this, the last time we see her is in a flashback from the flashforward that comprises the final issue (it makes sense in context).

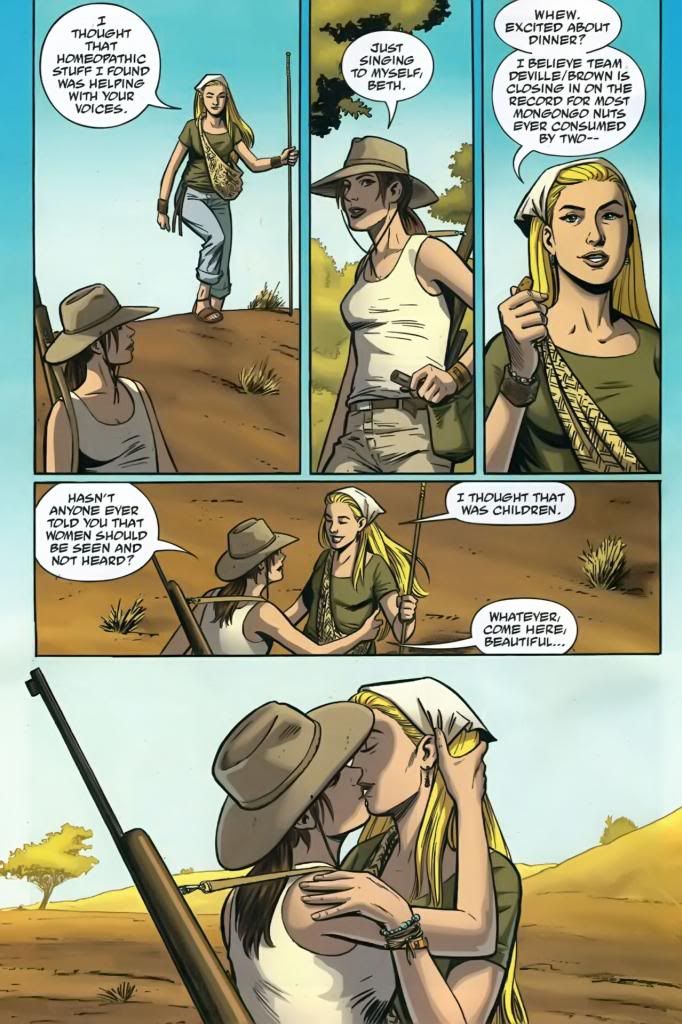

Around six years after the ending of the penultimate issue, Yorick journeys to the Kalahari to give Hero the late Agent 355’s collapsible baton. He jokes that she’ll “be less likely to shoot [her] eye out with it while [she’s] out here doing [her] whole ‘white woman’s burden’ thing.” Hero protests, saying that it’s the lionesses, and not the native population, who need their help. She waxes poetic about the women’s ability to adapt following the gendercide, and Yorick remarks that she “even sounds like her.” It turns out that the “her” in question is Beth Deville, who ended up as the love interest for the other Brown sibling. The evolution of their romantic relationship occurs entirely off-panel, so it reads as a bizarre twist instead of an organic development. The only explanation is that the hero has to get the girl, even when there’s no build-up whatsoever. It’s an amusing play on a tired trope, but it still posits Beth as a prize to be gifted by the narrative to whomever it sees fit.

Ultimately, my problem with Beth is that her story doesn’t go far enough. We are told that she’s more than a MacGuffin, but the moment she gains agency and subjectivity, she is removed from the narrative. We get to see her thoughts, but all of these thoughts revolve around Yorick; it’s so bad that the only conversation she recalls having with Hero -- the person she ends up with -- is actually about the other woman’s brother. It’s understandable for reasons of streamlining the narrative, but it leaves Beth woefully underdeveloped. She may not be an object, but she’s also in no way a fully realized character.

Verdict: Love Interest