| All screencaps: Piandao.org |

In the original plan for Avatar: The Last Airbender, Katara was the only female member of Team Avatar. Aang’s earthbending teacher was originally conceived as a “big, muscly kind of jerk guy” who would serve as a foil to Sokka’s nerdiness. Early production notes indicate that this character would have attracted Katara’s romantic attention, making the Katara/Aang relationship into a love triangle. Luckily, head writer Aaron Ehasz noticed the gender disparity and lobbied for the earthbender to be a girl. And thus Toph Beifong, the Blind Bandit, the Runaway, the Melon Lord, and the greatest earthbender in the world, was born.

Even in the early stages of her development, the character who would become Toph was blind. In most mainstream films and television shows, characters with disabilities are defined by them. Stories about these characters revolve around how very unfortunate it is that they can never lead a “normal” life, and these narratives typically suggest that every person with a disability resents their situation. Most of the time, however, these characters aren’t even represented, limited instead to Very Special Episodes in which the abled members of the main cast learn lessons about tolerance. Often, these one-off episodes portray the abled person admiring the person with a disability for their optimism in the face of terrible hardship. Basically, most media treats disability as a horrible affliction that we must look beyond, even as it ensures that all stories about people with disabilities are about their disabilities, not about their personalities or accomplishments.

Before Toph enters the narrative, the show subverts this pattern with Teo, a boy paralyzed from the waist down whose inventor father builds him a glider that allows him access to the skies. Unfortunately, though he does return in the third season, his story is almost entirely limited to one focal episode. Toph, by contrast, is a principal character, one of the uncontested main members of Team Avatar.

Toph’s introductory episode is an explicit rebuttal to the typical portrayal of people with disabilities. The first time we meet her, she is defending her title at a WWE-style earthbending competition as the Blind Bandit. Aang, Katara, and Sokka are initially skeptical; surely a tiny twelve-year-old blind girl couldn’t beat a bunch of full-grown men. However, she can and does, and she is only defeated when Aang unfairly uses airbending in his challenge for the title.

When she disappears afterwards, Aang must use clues gleaned from a vision to find her, as no one knows who she is. It turns out that she is the only child of a wealthy couple who have kept her existence secret in order to keep her safe. They are exceedingly overprotective, limiting her to beginner level earthbending lessons, and having servants not only supervising her when she goes out on the grounds, but blowing on her soup when it’s too hot. She is a prisoner in a gilded cage, and her repeated escape attempts do nothing but move the bars closer.

Later in the episode, after she and Aang have been kidnapped, Toph’s father reveals that his primary reason for keeping her close is her blindness. When Sokka and Katara ask for her help to save Aang, her father states, “My daughter is blind. She is blind and tiny and helpless and fragile. She cannot help you.” Toph, confronted with her father’s low opinion of her ability, says simply, “Yes, I can.” Sokka and Katara offer to help her, but she declines. Then she takes on all seven adult earthbenders at once and she wipes the floor with them.

Even in the face of a display of bending that floors master waterbender Katara, Toph’s father refuses to accept that she can take care of herself. He concludes that she’s had too much freedom and puts her under twenty four hour surveillance. Finally, she escapes one last time to join Team Avatar, claiming that her father changed his mind and is now perfectly fine with letting her travel the world. The last we see of her father, he is ordering two earthbenders to “do whatever it takes to bring her home.”

Toph’s father is presented as controlling and irrational, and the show condemns his point of view. He is wrong for controlling her and for viewing her in terms of what she can’t do instead of who she is. By condemning him, the show rejects the usual approach to the mainstream portrayal of disability. It strengthens this message by having Toph defend her actions with very little reference to her blindness, instead framing the conversation as a matter of agency versus control. She doesn’t explain that she has devised a method of sight that involves reading vibrations in the earth, thereby “overcoming” her disability. Rather, she points out that she’s good at fighting, that she loves it, and that she deserves to exist and be accepted as she is. Ultimately, she joins Team Avatar because they can give her that acceptance.

That’s not to say that the other kids don’t say insensitive things; in fact, one of the most compelling aspects of the show’s treatment of this issue is that it never entirely becomes a non-issue. It can be difficult to find a balance between normalizing a disability and erasing it, and I think Avatar: The Last Airbender does an admirable job. While the show never focuses another episode around Toph’s blindness, it also doesn’t let the audience ignore it and pretend she’s just like everyone else. She’s not, and that’s completely fine. The way it accomplishes this is through the power of jokes. When the group takes cover in a hole, Sokka laments that “It’s so dark down here. I can’t see a thing.” Toph responds, “Oh no, what a nightmare,” and Sokka apologizes. When they’re looking for things, she takes great delight in pretending to see them, only to remind her friends that she can’t. It’s a fun way to remind the characters and the audience that she experiences the world differently without making this difference a big deal.

The shift in Toph’s loyalty from her biological family to her found family forms the bulk of her character arc, and it is best exemplified in the development of her relationship with Katara. In “The Chase,” nurturing team mom Katara comes into conflict with the recently liberated Toph. Toph refuses to help the others set up camp, claiming that she can pull her own weight. The tension increases over the course of the episode, in which Team Avatar endures a sleepless night spent fleeing from Azula’s relentless pursuit, eventually causing Toph to leave the group. She runs into Zuko’s uncle, Iroh, to whom she confesses, “People see me and think I’m weak. They wanna take care of me, but I can take care of myself, by myself.” Iroh tells her that there is nothing wrong with getting help from the people who love you, and she decides to rejoin the team.

The tension between Toph and Katara can be traced to a myriad of sources. First, their respective elements are incompatible; while Katara is all about the push and pull of compromise, Toph is stubborn and rigid. Katara is also suffering from some serious disillusionment, as she thought that adding another girl to the group would give her the opportunity to bond with someone like her. Instead, Toph turned out to be very much “one of the guys.” This would be especially difficult to take for a girl who had no friends of her own age in the South Pole. Because she had never had a friend in her entire life, Toph probably seemed like the perfect candidate for companionship. As if that weren’t enough, Katara’s need to take care of others conflicted with Toph’s need to prove that she could fend for herself. Katara falls into a maternal role, and Toph is more interested in discovering what life is like without parents.

The issues raised in “The Chase” are resolved a season later in “The Runaway.” The episode begins with Katara and Toph sparring with Aang as part of his training. The training session quickly devolves into a fight between the two girls which ends in the G-rated, water- and earthbending equivalent of mud wrestling. Their tension thus firmly re-established, Toph basically sets out to tick Katara off. She does this by using her bending to pull a number of scams, first sensing the rock in the shell game, then eventually building to full-on blackmail. Katara warns her that she’s playing a dangerous game that could get all of them caught, a particularly serious situation considering the fact that they are in the Fire Nation. Her prediction promises to come to fruition when Sokka discovers a “wanted” poster for a girl known as “the Runaway.”

By this point, Katara and Toph have explicitly reassumed their mother and child roles. Katara thinks that Toph is acting out because she misses her parents and can’t deal with the fact that she still loves the two people she pretends to hate. Toph seems to resent Katara for trying to act as her mother. Later, she reveals to Sokka that she has conflicted feelings about Katara’s maternal qualities: “The truth is, sometimes Katara does act motherly, but that’s not always a bad thing. She’s compassionate and kind and she actually cares about me -- you know, the real me. That’s more than my own mom .”

Toph’s reckless behaviour takes on new significance in light of this confession. On some level, she seems to be asking for someone to discipline her; she needs Katara to provide order and rules. She needs Katara to fulfill the role of a mother, to care for her and protect her from her own bad ideas. This might be another reason for Toph to act out; she has to know that Katara will acknowledge her flaws, because that means that she cares for Toph the person, not Toph the idea. While she could look for validation from Aang and Sokka, neither her god-like student nor her crush can really fill that parental role.

Katara tries to re-define their friendship as a relationship between equals by offering to pull a scam with Toph. In this way, she can show Toph that she’s fun while hopefully removing the baggage of projected parental failure from their relationship. At the end of the episode, Toph tells Katara that she was right and asks Katara to help her write a letter to her parents, thereby relieving her of her role as maternal figure as Toph seeks to re-open communication with her actual mother.

Further proving the importance of her relationship with Katara is their shared vignette in “Tales of Ba Sing Se.” After observing that Toph has “a little dirt on [her]... everywhere, actually,” Katara suggests that they have a girls’ day out at the spa. It’s not really Toph’s scene, and she says as much; still, she makes it through, and even enjoys it, albeit with the help of humourous earthbending hijinks. Afterwards, a group of girls insult her makeup, and she opens up the stone bridge to dump them in the river, with Katara helping to punish them by floating them away on a wave.

The exchange that follows is remarkable. Katara tries to tell Toph that the girls had no idea what they were talking about, but Toph assures her that “It’s okay. One of the good things about being blind is that I don’t have to waste my time worrying about appearances. I don’t care what I look like. I’m not looking for anyone’s approval. I know who I am.” Still, she’s crying as she says it. Katara notices and tailors her response to reinforce Toph’s value as a person, even as she also addresses the unspoken question: “That’s what I really admire about you, Toph. You’re so strong and confident and self-assured, and I know it doesn’t matter, but you’re really pretty.” This response earns Katara the (should-be) coveted Beifong shoulder punch of affection.

This vignette accomplishes a lot in a very short time. It frames the spa trip more as an opportunity for the two girls to bond than a foray into beautification. It allows us to see how Katara and Toph’s relationship works when it’s not bogged down in mommy issues. It argues that women and girls should be defined by their personality instead of their appearance without demonizing the pursuit of beauty. Most notably, it removes the validation of women’s appearances from the realm of the male gaze. Girls insult Toph’s makeup, she and another girl punish them for their hurtful comments, and a girl tells her that she’s pretty. While it depicts women as the harshest critics of other women’s looks, it also suggests that women can build each other up and bolster each other’s self-confidence.

This is particularly interesting in light of Toph’s complicated relationship with gender performance. Whereas Katara fights to be allowed access to traditionally male spaces, Toph’s domination in Earth Rumble V and VI proves that she’s already there. As far as we know, she spent all of her time at home with her parents and servants, with regular visits from her earthbending teacher, Master Yu. It’s no surprise that a sheltered, disempowered kid would want to emulate the competitive earthbenders’ overt displays of strength and forge a place for herself among them. Joining their ranks, however, necessarily requires her to immerse herself in their hyper-masculine subculture, based on violence and trash talking. Toph happily becomes a master of both.

One of the more problematic behaviours that Toph picks up from the competitors is her tendency to base jokes on the denigration of stereotypically feminine traits. For example, when Aang challenges her to a match, she asks, “Do people really want to see two little girls fighting out here?” She calls him “light on his feet,” “Fancy Dancer,” and “Twinkletoes,” the last of which becoming her official nickname for him. She tends to view strength as physical power, and she obviously associates physical power with masculinity.

This becomes evident in the “Ember Island Players” episode. Before the four-part finale, Team Avatar goes to see a play about their adventures. The play is unutterably awful, mischaracterizing literally every single person (though nowhere near as terribly as the actual adaptation by M. Night Shyamalan, as these characterizations at least have some foundation in canon). Aang is an irritatingly cheerful woman, Sokka is a useless jester, and Katara is a moralizing crybaby with lines like, “My heart is so full of hope that it’s making me tearbend!”

During the first intermission, the kids complain about their portrayal. Toph, who won’t be showing up until the second act, just tells them that the truth hurts. Her friends tell her to wait for her own depiction, confident that it will be just as offensive. Toph emerges onstage as a massive, muscular man, introducing himself as Toph, “because it sounds like ‘tough,’ and that’s just what I am.” Unlike her friends, Toph is ecstatic, and she says that she wouldn’t have cast it any other way. Then the actor Toph explains that he can basically use echolocation, and the real Toph beams.

The play is a clever take on a Hollywoodized A:TLA; therefore, both the actor’s ridiculous onstage antics and Toph’s reaction to her own representation can be read as commentary on the process of adaptation. A paragon of masculinity, size, and physical strength, actor Toph is what Hollywood usually chooses to depict when it must portray a cocky, powerful character. Even A:TLA almost perpetuated this uninspired portrayal in its original plan for Toph. In this moment, we see just how subversive Toph’s character really is. While her introduction hinged on the audience’s reluctance to see a tiny blind girl as a powerful figure, the deeper meaning of this scene relies on the audience’s knowledge of Toph’s strength. To an audience familiar with Toph’s accomplishments, the notion that this muscled giant is in any way her equal is laughable. She has real power, while he has ridiculous bravado. She has displaced him as the true possessor of strength, and he stands as an empty symbol. However, the fact that Toph then tells Aang, “At least it’s not a flying bald lady,” suggests that she herself still values (her flawed perception of) masculinity above (her equally flawed perception of) femininity.

This makes sense when you consider Toph’s approach to earthbending. To her, bending is all about being firm and grounded, and it is best taught by inflicting pain and slinging insults. When a blindfolded Aang moves out of the way of a rolling boulder that he was supposed to stop, she exclaims, “If you’re not tough enough to stop the rock, then you could at least give it the pleasure of smushing you instead of jumping out of the way like a jelly-boned wimp!” Katara warns her that Aang responds better to positive reinforcement, and Toph gets a chance to test this theory when he fights off a saber-tooth moose lion and stands up to her psychological assault. “You just stood your ground against a crazy beast,” she says. “And even more impressive, you stood your ground against me.” It is only after Aang has proven himself to be solid and forceful that Toph will call him an earthbender.

Earthbending forms the core of Toph’s character. It is ingrained in her personality, from her direct approach to problem-solving to her plain-spoken wisdom to her rock-solid sense of self. The reason for this lies in her own instruction in the art at the paws of the original earthbenders: the badgermoles. She explains: “They were blind, just like me, so we understood each other. I was able to learn earthbending, not just as a martial art, but as an extension of my senses. For them, the original earthbenders, it wasn’t just about fighting; it was their way of interacting with the world.”

Toph’s reliance on earthbending is her greatest strength and weakness. It allows her to detect lies, save her abled friends, and hold up entire buildings against the force of angry spirits. It also makes it nearly impossible to “see” anything clearly when she is on wood, sand, or ice, leaving her helpless in many dangerous situations. However, Toph refuses to remain weak, so she does everything she can to adjust to these materials. Wood and water are a lost cause, but she goes from perceiving everything as “fuzzy” when walking on sand to bending it into a scale model of Ba Sing Se, complete with the Earth King and his pet bear.

It is in the moment when she is most vulnerable that Toph discovers her greatest strength. In the final two episodes of the second season, the two men Toph’s father paid to kidnap her finally succeed. To do this, they send a letter ostensibly penned by Toph’s mother, telling Toph that she is in the city and asking her to come visit. They play off of Toph’s love for her mother; while her father made his opinion of her very clear, her mother says little enough that she might believably be willing to get to know the real Toph. Toph’s unrequited familial love is only the first vulnerability that they exploit; when she arrives at the house, they lock her in a metal box.

Up to this point, one of the incontrovertible truths of the A:TLA world is that it is impossible to bend metal. Xin Fu says as much when he tells Toph, “You might think you’re the greatest earthbender in the world, but even you can’t bend metal.” For a time, even Toph believes this. As all of her ploys to get out of the box prove unfruitful, however, she looks to the metal itself. Overlaid on the scene is the voice-over of a guru, telling Aang that all of the elements are connected. Even metal, he says, is just “a part of earth that has been purified and refined.” Without the benefit of hearing this voice-over, Toph nevertheless finds the impurities in the metal box and physically pries it apart. When her captors come back to investigate, she imprisons them in the box, exclaiming as she leaves, “I am the greatest earthbender in the world! Don’t you two dunderheads ever forget it.”

In this scene, we see the essence of Toph. She finds herself in a seemingly impossible situation, so she does the impossible to get out of it. She has been locked in a cage -- a metal box, the prison of her parents’ house, the jail of their controlling affection, or the dark dungeon that others assume she is confined to due to her blindness -- and she forges her way to freedom. Ultimately, Toph Beifong is a character who finds empowerment in disempowerment, turning perceived weaknesses into real strengths.

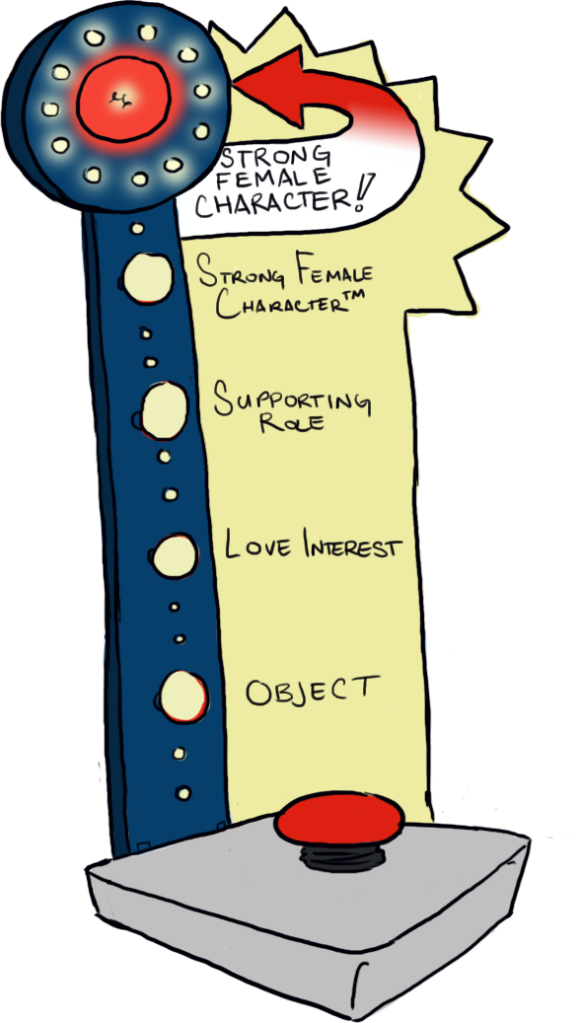

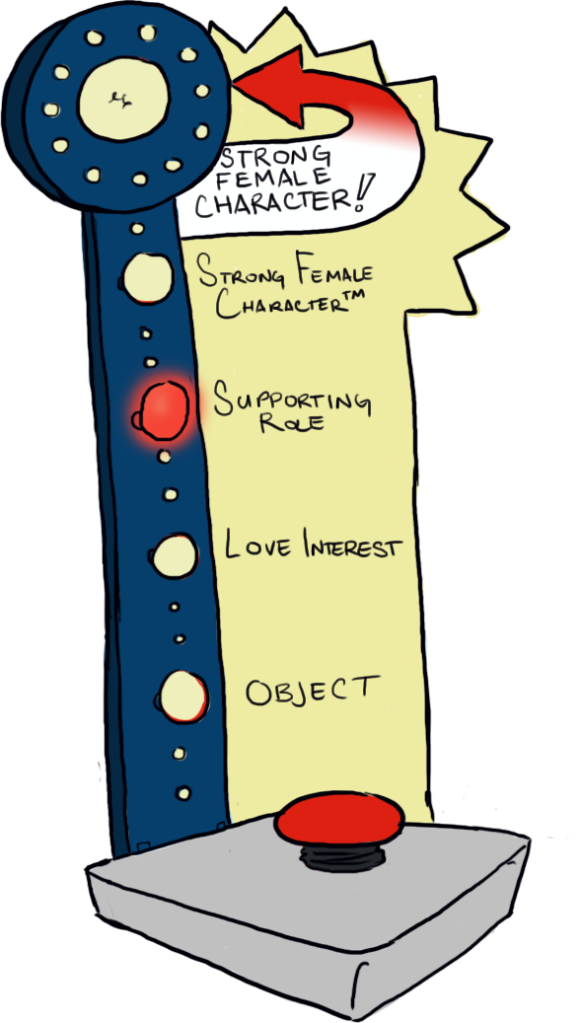

Verdict: Actual strong female character