In

honour of the holiday season, this week we’re going to do something a

little different. At this time of year more than any other, we face a

constant onslaught of advertising, telling us what we should want and

who we should want to be. To us, this is yet another opportunity for the

media to misrepresent, well, whole swaths of people, but often women

and girls in particular. So, in another nod to the commercial Christmas

spirit, we’d like to discuss the gender segregation of holiday

advertising and why it just might be the most frustrating part of the

so-called happiest time of the year.

A

couple of weeks ago, my mother and I went shopping for some clothing

for my nephew and cousins. As we entered Carter’s-OshKosh, I was taken

aback by the difference between the two sides of the store. On the right

side, there was a wide variety of clothing styles in a vast array of

colours; on the left there was... pink. One side looked like a kids’

clothing store, and the other looked like a Valentine’s Day display.

Now, don't get me wrong. Pink as a colour is lovely; pink as a visual indicator of an object's "girls only" status is not.

We

checked out the boys’ side first, its gender affiliation made obvious

by the fact that none of the shirts had random ruffles on them. When it

came to picking things out for my nephew and cousin, we were spoiled for

choice. Then we entered Girl World, where everything was pink and

sequined, emblazoned with floral patterns or “cute” sayings (or, in many

cases, just the word “cute”). Throwing a glance back into Boy World, I

noticed a shirt that read “Boy Genius;” turning to the ultra-feminine

landscape before me, I glimpsed the girls’ equivalent: a shirt

emblazoned with a heart and the words “Seriously Cute.” Eventually, we

completed our expedition, having secured a single specimen of the rare

green shirt. I might have thought it had escaped from Boy World, if the

ruffles didn’t prove that it was native to the region.

This

was such a troubling experience, I think, not because the gender split

was new or surprising, but because it was so starkly represented.

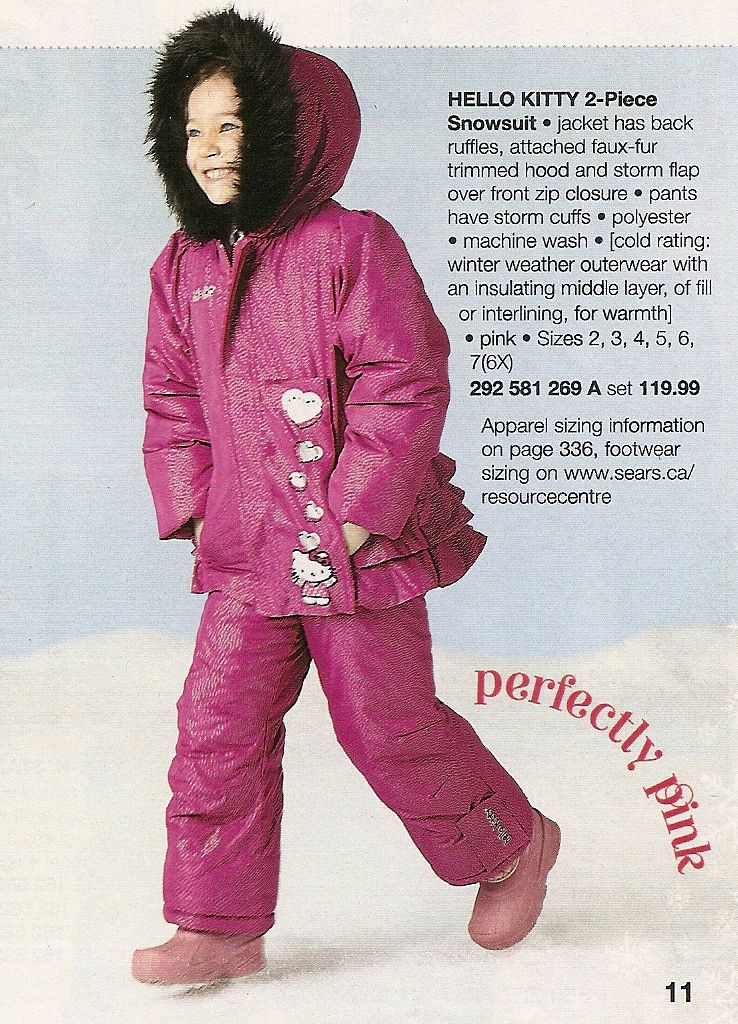

And brick and mortar kids’ clothing stores are hardly the only ones guilty of this rigid categorization. In the Sears Wish Book,

a catalogue I’ve browsed every December for as long as I can remember,

something like the first few dozen pages are split into gift types like

“Cute Gifts” and “Gamer Gifts.” This seems like an admirably

gender-neutral approach, until you actually pay attention to the models

using the items advertised. “Gamer Gifts” features T-shirts that are

only available in men’s sizes, “Totally Cool Gifts” shows a boy using

spy gear, and “Galactic Gifts” (or “Star Wars Paraphernalia,” as it

could also be known) contains both of these signs of female exclusion.

Girls and women do get some items in “Super Gifts” (superhero things)

and “Winning Gifts” (hockey stuff), but their only major categories are

“Cute Gifts” (so much pink and Hello Kitty, it burns) and Playboy

accessories. As if that weren’t enough, the “Galactic Gifts” spread

shows a boy wielding a lightsaber with the words “take that, galactic

empire” written across the image; by contrast, the “Cute Gifts” model is

a girl in a pink Hello Kitty snowsuit just walking with an utterly

unnecessary “perfectly pink” written next to her.

This

continues throughout the catalogue, to the point that I actually

started treating it as a bit of a guessing game. What gender was the

model pictured using a punching bag? What about the superhero action

figures, the fake guns, the toy cars, or anything from the movie Cars?

Who could possibly be pictured playing with fairies, dolls, tea sets,

or anything pink and princess-y? The answers are disturbingly obvious.

As

for clothing, again, the shirts on offer for girls champion really

dubious things. One has the image of Smurfette and the words “Born to be

famous,” while another shows an image of Hello Kitty wearing glasses

and the text, “Geek is the new cute.” While boys get shirts depicting

superheroes and proclaiming their superior intelligence, girls get the

message that their value is based on their appearance and their

celebrity. And, while the latter would be pretty cool if the girl in

question became famous for wielding major political power or making an

important scientific discovery, the fact that they used Smurfette

somehow suggests otherwise.

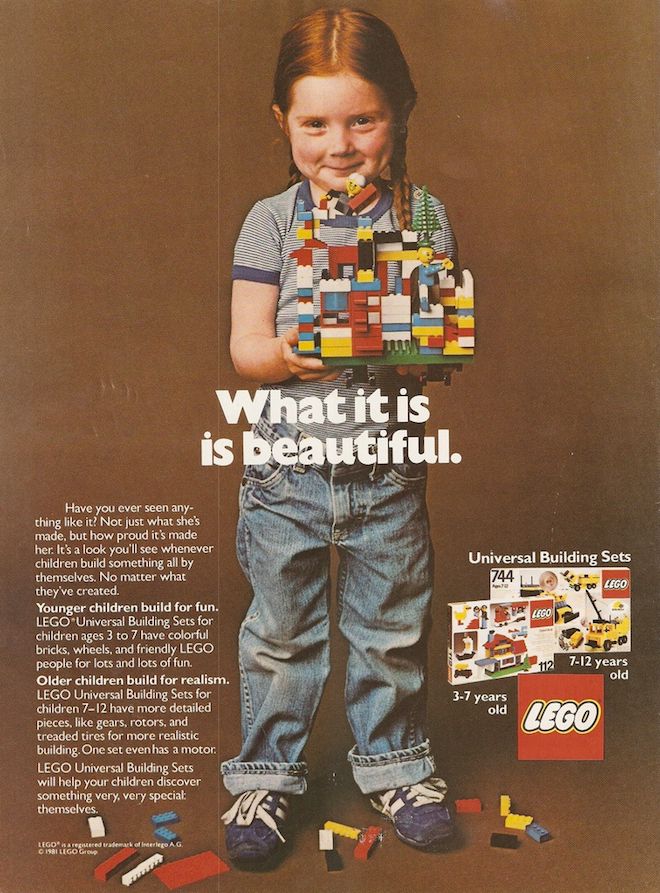

This

is not to say that beauty can’t be part of the marketing for girls.

Just look at this ad from 1981. First, nothing in this picture is pink.

The girl is using real Lego and not the awful new Lego Friends sets;

it’s a house that she created, not one that was pictured on the side of

the box. More importantly, though, it’s the house that is labelled

“beautiful,” not the girl. What is beautiful is the object she made and

the imagination that produced it.

I

mean, read the accompanying text: “Have you ever seen anything like it?

Not just what she’s made, but how proud it’s made her. It’s a look

you’ll see whenever children build something all by themselves. No

matter what they’ve created.” That description, in and of itself, is a

beautiful thing.

Unfortunately, that ad was released more than thirty years ago. Today, Lego produces ads like this one.

But

all hope is not lost. In a viral video that has amassed over four million hits, a little girl named Riley Barry manages to isolate the

problem of gender-stereotyped marketing while standing in the middle of

an aisle of girls’ toys. She bemoans the fact that most of the toys

being marketed to her demographic are pink, and argues that both girls

and boys would like to play with both dolls and superheroes. Even if she

is merely parroting what she’s heard her parents say, as some critics

have claimed, there are certainly worse things for parents to teach

their children than to question the social roles they are paying to

embrace.

Thirteen-year-old

Mckenna Pope has started a campaign to get Hasbro, the manufacturers of

the Easy Bake Oven, to include boys in their marketing. Her younger

brother wants the toy for Christmas, but he has been convinced by the

advertisements that the product is only intended for girls. Mckenna’s petition on Change.org has collected over 31,000 signatures. (I signed

it, because I had an Easy Bake Oven and I fully support any campaign

that would allow all children to feel the pride that comes with eating

that first batch of barely edible brownies.)

Real

change has already occurred in Sweden, where the largest toy chain, Top

Toy, has changed its marketing to a gender neutral model following a

reprimand for discrimination by the country’s advertising watchdog.

Their catalogue now shows boys playing with dolls and girls wielding toy

assault weapons. It’s awesome.

Then

there’s the response to one of my personal favourite marketing fiascos

of the last year: the Bic for Her pen. Both men and women responded to

the premiere of the “lady-pen” with often hilarious reviews, many female

reviewers’ comments made all the more perfect by the thinly-veiled

bitterness caused by a lifetime spent having to buy things that are

strong enough for a man, but made for a woman. Even Ellen Degeneres

weighed in, a few weeks late but scathing enough to make up for the

delay.

We’d

like to end this post on a truly positive note, but all we can really

say is that, although gender stereotyped marketing is pervasive and

pernicious, there is hope. Just, ironically, not around Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment