There

is something inherently cool about intergalactic Westerns. This is

partially because, just like that thing where you improve fortune cookie

fortunes by adding “in bed” at the end, there is nothing that cannot be

made cooler by adding “IN SPACE!” Accountants... IN SPACE! Fast food

franchisees... IN SPACE! Farm boys who used to bull’s-eye womp rats in

their T-16... IN SPACE! It’s really no surprise then that a show with

the premise “Cowboy smugglers... IN SPACE!” would catch on.

Sadly,

it’s also no surprise that the show never really delved into the issues

that arise from melding nineteenth century scenarios with a futuristic

setting. It revelled in nostalgia while simultaneously asserting its

progressiveness. Nowhere is this clearer -- or more problematic -- than

in the characterization and treatment of Inara Serra.

Intelligent,

self-confident, and assertive, Inara is a fascinating character. Eight

months before we meet her, she left everything she knew behind on the

planet of Sihnon, where she spent her life training and working as a

Companion. Companions are one of Whedon’s innovations, and they work

well in concept. Replacing the ubiquitous prostitutes of the classic

Western, Companions are highly trained women who hire themselves out as

sexual partners and social accompaniment. Their work is both legal and

respectable, and their status allows the vessels they travel on access

to higher class planets. Their training covers music, art, combat, and

psychology, and they are expected to cultivate these skills with

practice. They choose their own clients and, when a client misbehaves,

they possess the ability to blacklist them and prevent them from ever

hiring another Companion.

Because

its foundation is female sexual agency, the concept of the Companion is

fairly progressive; however, the execution in the show is incredibly

dubious.

The

first and most obvious problem with the Companion model is

representative of a problem with the show in general: its egregious

displays of Orientalism. While the world of Firefly

is clearly inspired by Asian culture, it’s mainly used to spice up the

otherwise traditional Western feel of the show. Some people -- mostly

extras -- wear Asian clothing, do Asian dances, or, you know, are even

sometimes Asian themselves. A street vendor’s sign advertises snacks

made of dog meat. The main cast -- none of whom are Asian -- curse in

poorly pronounced Mandarin. The Companions are based on oiran,

Japanese courtesans somewhat similar to the more well-known geisha. As

if it weren’t enough that the only principal characters with an Asian

surname are a doctor and a martial artist, the most visible piece of

Asian culture feeds into the Western conception of the East as a land of

sexual pleasure.

Another

problem that I have with the Companion lies in the show’s treatment of

what could have been a legitimately progressive part of their practice.

In “War Stories,” the B plot consists of Inara entertaining a client

onboard the ship. Although she explicitly asks for privacy, several of

the other crew members look on as the client boards and they all react

with shock when, wonder of wonders, the client is a woman. Jayne

immediately takes the situation as masturbation fodder and states, “I’ll

be in my bunk.” He repeats the phrase (and the lecherous look) later

when he sees the councillor and Inara share a quick peck as the

councilor departs.

Identifying

Jayne with the male gaze may have allowed the writers a great

opportunity to explore the difference between the fetishistic fantasy of

lesbian sex and the reality of physical love between women and, on the

surface, that’s precisely what they did. In the privacy of her shuttle,

Inara gives the councillor a massage and commiserates with her about her

need to “relax with someone who’s making no demands on me.” Inara

informs her that, while the majority of her clients are men, she

sometimes feels the same way; as she observes, “One cannot always be

oneself in the company of men.”

Unfortunately,

the larger context for this scene undermines its value, in the sense

that there is no larger context. Whereas other episodes tend to make use

of Inara’s clients in the plot, the councillor plays almost no role at

all, providing only the equipment to reattach Mal’s ear after his

tormentor removes it. This lack of relevance, in combination with the

long, lingering shots of the councillor’s naked back in the scene from

which the male gaze was ostensibly banished, suggests that the

introduction of a female client was all about “the show.” The dialogue

makes it out to be Inara and the councillor’s escape from male eyes, but

the way it’s shot and the way it simply doesn’t matter to anything else

makes it gratuitous. By this time, we are also well aware that Inara’s

actual love interest is a man, so the scene also perpetuates the idea

that bisexual women prefer men. Finally, it’s tough to shake the feeling

that this otherwise useless subplot was only included to get Whedon

points for LGBTQ representation in a show where everyone else reads as

straight.

I’m not saying it’s enough to ruin “I’ll be in my bunk”; I’m just saying that it should be.

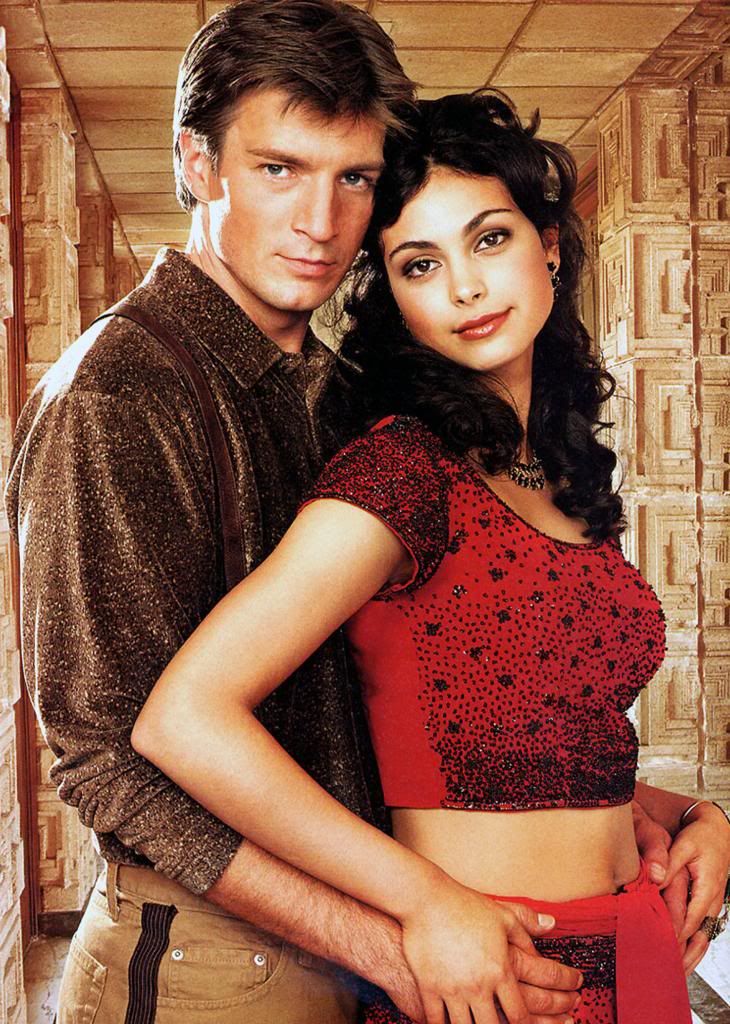

Now we come to the point in this post where every Firefly fan gets the sudden urge to cause me bodily harm. Why? Because I’m going to bash Captain Tightpants.

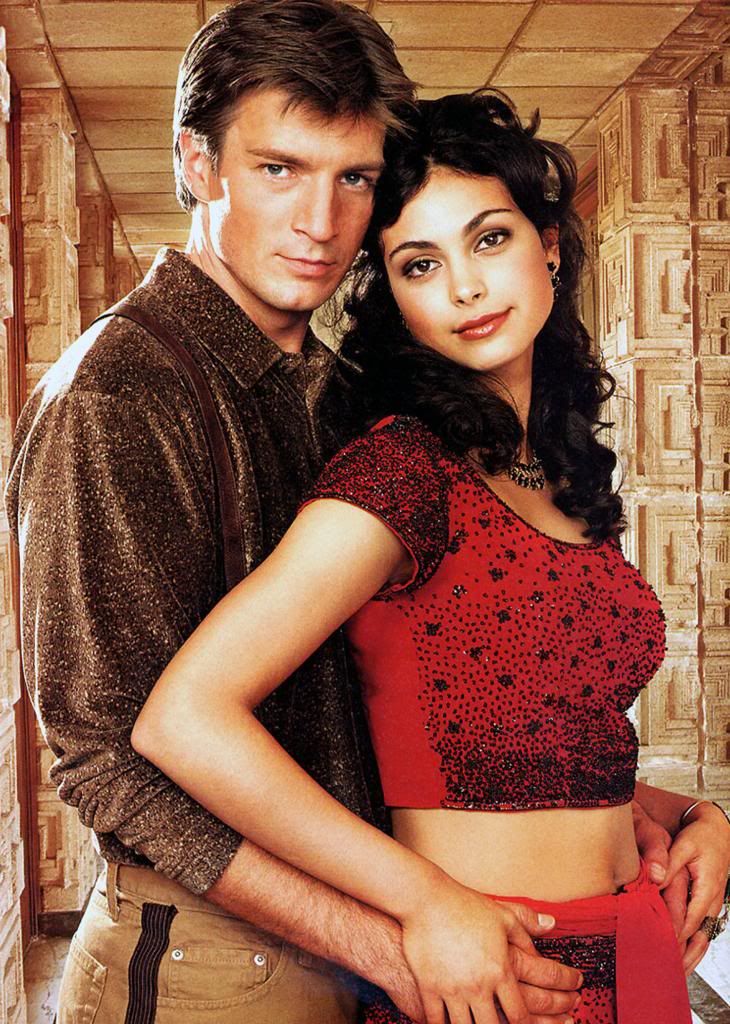

Most

of Inara’s screen time is spent with Mal, and they spend the vast

majority of this time arguing in the way that tells every television

viewer that they’re besotted with each other. We know that Inara is in

love with Mal as early as the pilot, in which she tells Shepherd Book,

who’s trying to figure out the mystery that is the captain, that it is

his unpredictable quality that attracts her. Among all the men she’s

known, Mal is the only one she considers a mystery.

To

me, the greater mystery is why she puts up with him. Existing as it

does to glorify the flawed perfection that is Malcolm Reynolds, the show

can’t help but bring Inara along for the ride. To this end, we get the

“whore” problem. While a Companion’s work is established to be about

spiritual connection, artistic cultivation, and women’s sexual agency,

Mal reduces it to sex and money. Despite the fact that Inara explicitly

tells him on their first meeting never to call her “whore,” he turns it

into a kind of term of endearment, as if it could be endearing to be

constantly degraded. Also apparently endearing is his violation of her

personal space. One of the conditions of their rental agreement is that

no one enters her shuttle without her permission; despite Mal’s initial

agreement, he constantly shows up unannounced. He disrespects her just

about every time they talk.

This

is why I find one of their arguments particularly disturbing. In

“Trash,” Inara confronts Mal about the fact that he has been avoiding

taking jobs on planets where she can work. The argument builds until

Inara calls Mal a “petty thief,” at which point the conversation

screeches to a halt. He takes offense, she scrambles to lessen the blow,

and I pause the episode in outrage. In previous episodes, Inara often

calls Mal out for calling her a “whore” (which he does earlier in this

argument) and, although it still seems that we are supposed to be firmly

Team Mal in all of this, it’s still possible that the show wants us to

see his slut-shaming as a character flaw. And then this happens.

Somehow, in the world of Firefly,

calling a man a “petty thief” is more insulting than calling a woman a

“whore.” For some reason, a woman who has every right to object to this

disrespect is made to be the bad guy.

This

is part of a troubling pattern that emerges in the show’s treatment of

Mal’s slut-shaming of Inara. In “Shindig,” Inara gets work with a

wealthy client, Atherton Wing, who offers her a position as his personal

Companion and a place in the upper echelons of his planet’s society.

Basically, he seeks to own her. As the episode goes on, we see him

become increasingly possessive, holding Inara’s arm and observing that

he “know[s] what’s mine.” There’s no question that he is a Bad Guy.

There

is also no question that Mal is then set up as the Good Guy. While

Inara is blind to Atherton’s true intentions, Mal sees him for what he

is. He tells Atherton that Inara doesn’t belong to anyone and punches

him just before he can finish saying that Inara is “still just a whore.”

It turns out that the punch signalled Mal’s desire to duel Atherton for

Inara, and we are suddenly left with a situation in which a woman’s

agency is completely lost. It doesn’t matter what Inara wants, because

she’s not the one making the decisions. In fact, the show gives her a

champion to fight for her right to make her own choices.

Again,

because he is fighting for Inara’s agency, Mal is the hero. It doesn’t

matter that she didn’t want him to defend her honour, and that, by

starting this fight in the first place, he ignored her wishes. Indeed,

she even thanks him for doing it at the end of the episode. Still, Inara

is willing to question this sudden concern for her honour. As she says,

“You have a strange sense of nobility, captain. You’ll lay a man out

for implying I’m a whore, but you keep calling me one to my face.” He

replies, “I might not show respect to your job, but he didn’t respect

you. That’s the difference.” While the show tells us that Mal respects

Inara, there is ample evidence to the contrary. In this episode alone,

he defies her wishes and messes with her job. He shows no respect for

the boundaries that she has established as part of their legal

agreement. In a later episode, he belittles her value to others when,

after a distress call comes in asking for Inara’s help, he asks, “This

distress wouldn’t happen to be taking place in someone’s pants, would

it?”

In

short, he’s the good guy because he’s not the worst. He’s better than

Atherton who, after losing the duel, tells Inara that he should have

“uglied [her] up so no one else would want [her].” That suggests that

the bar is set pretty low, and Mal making it over doesn’t mean that he

should be seen as a good partner for Inara, or even a particularly

positive influence in her life.

This

brings us to one of Inara’s defining moments: the decision to leave

Serenity. The decision appears to be influenced by two things: the death

of her old friend, Nandi, and Inara’s realization that she is too

invested in her non-relationship with Mal. She identifies a similar

strength in both Nandi and Mal, and she states that, “when you live with

that kind of strength, you get tied to it, you can’t break away, and

you never want to.” By resisting the pull of that strength and walking

away from a situation that is clearly causing her pain, she displays her

own strength. In Serenity,

we see a similar display in her willingness to risk her own life by

preventing Mal from saving her from the Operative. When he saves her

despite this, he puts his crew in danger, which is precisely what she

was trying to prevent. She is able to see beyond her own desires to do

what’s best. Unfortunately, this doesn’t stop her from ending up in

exactly the same boat at the end of the film, back on Serenity with

nothing resolved.

Maybe that’s for the best. I know it’s practically blasphemous in some circles to say that you’re glad Firefly

was cancelled, but I honestly feel that way. A large part of the reason

is the planned gang rape of Inara by Reavers. Because it was never

actually written or filmed, I’m inclined not to include it in this

analysis, but I encourage you to read about it here. A word of

warning: what they were planning to do is horrific on a number of

levels.

This

is just further evidence of a major problem I have with the show.

“Cowboy smugglers... IN SPACE!” sounds like a cool idea for a show, but

giving the human society of 2517 (a period later than the entirety of

the Star Trek

canon) the same issues as late nineteenth and twentieth century Earth

is messed up. Compulsory heterosexuality and fetishization of queer

women? Still a thing. The stigmatization of sex work, even in a society

that has changed the perception of said work to make it a respectable

profession where women have power and agency? Alive and well. The

ongoing use of Orientalist stereotypes in a system where China

apparently defined much of the culture (even if everything else is based

on nineteenth century America)? Always. As if the aforementioned issues

weren’t enough, what we see of the Firefly universe

has a fully functioning patriarchy. The combination of nostalgia and

progress would be awesome if either aspect had been properly

interrogated, or if the show didn’t explicitly come down on the side of

nostalgia just about every time. It is almost as if the creators were

saying, “Take that, equality movements! Our fantasy world posits your

inevitable failure!” And there’s nothing cool about that.

Verdict: Somewhere between actual strong female character and Strong Female Character TM