I’d like to kick off this post with an assurance that I will be publishing the next installment of Reader Request Month: 2 Fast 2 Furious in the next day or two. I foolishly thought that I could keep up with my blogging even when, over the course of a week, my niece was born, I started a new job, and I departed for “the happiest place on Earth.” When I returned from Disneyland, I needed some time to settle into my new routine, but I should be on track to resume my regular schedule of weekend posts.

Back when I was a kid, I used to watch a commercial for Disney World on our Lion King VHS. As a five-year-old, I didn’t really understand the irony that made the ad funny, but I did know that I wanted to go to that park… or maybe the other one. I wasn’t sure at the time whether Disneyland or Disney World was actually closer. Not that it mattered; all I knew was that one day, I was going to visit Mickey and my beloved princesses.

Nineteen years later, that day arrived. I was initially worried that going to Disneyland for the first time as an adult would ruin my experience. This seemed even more likely in light of the fact that I’ve analyzed the very same princesses that I grew up blindly idolizing. Faced with the Disney machine, would I be able to enjoy the magical kingdom populated by characters I’ve loved for decades, or would I see only the money-making ploys of a corporate giant cashing in on manufactured nostalgia? The answer, it turns out, was both. Often at the same time. (In the interest of staying on topic, I’ll talk about only those things that relate to the characters we’ve discussed here on the blog.)

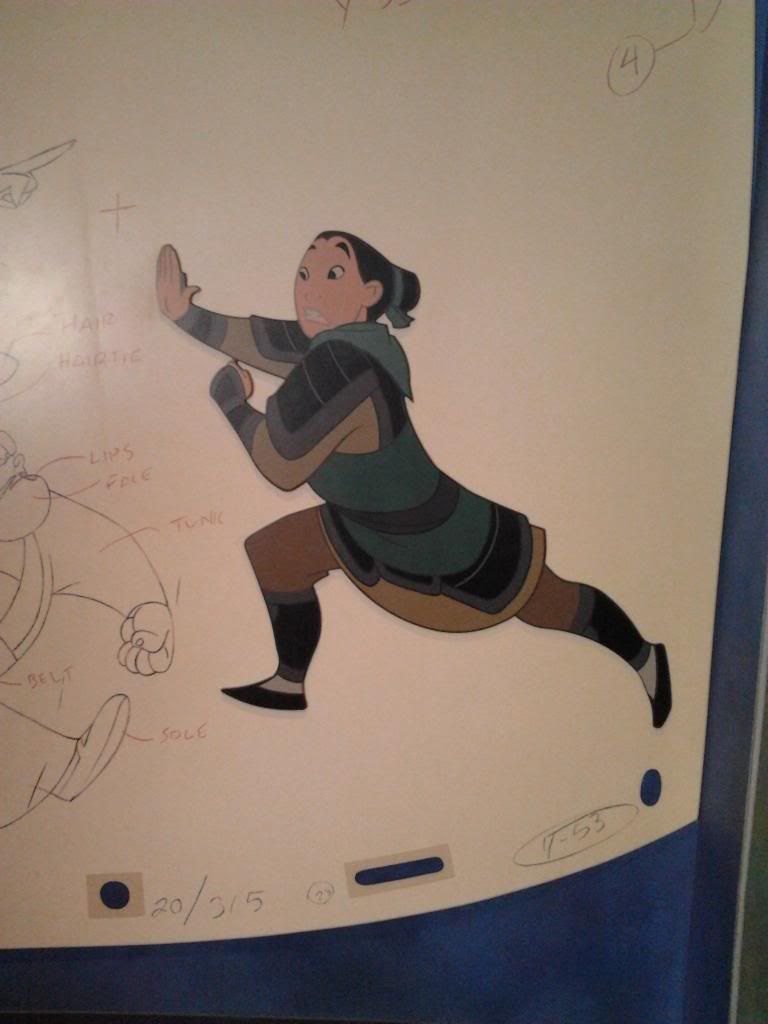

When I arrived at my hotel, one of the first things that caught my attention was a framed picture of the first six princesses: five white women and Jasmine. That proved to be the case throughout the park; most products only acknowledged the existence of eight princesses, invariably excluding Pocahontas and Mulan. Merida, having debuted after the success of Tangled made Rapunzel a necessary addition to any group photo, was left out, but still featured on a lot of Brave-specific merchandise. I knew that I would be leaving with some of it. But from the time I walked into the World of Disney store on the first day, I also knew that I was going to make it my mission to find things relating to Mulan and Pocahontas. When it came to merchandise, I was largely unsuccessful. Even in the land of imagination, it seems that no one can imagine people wanting products depicting all the princesses.

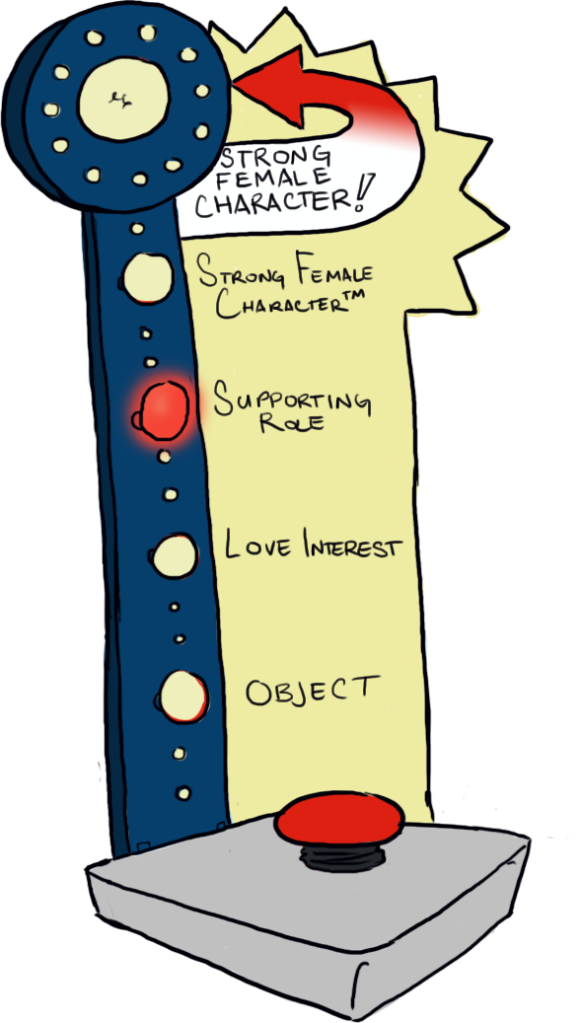

In the park’s major shows, however, I managed to find an interesting trend. In Mickey’s Soundsational Parade, Tiana gets her own float. In the abbreviated live musical version of Aladdin, Jasmine has a solo, “To Be Free”. Pocahontas has a featured segment in the World of Color show. She, Mulan, and Tiana all make an appearance in Mickey and the Magical Map. Disney is fine marketing an overwhelmingly white set of princesses to the masses, but when it comes to the parks, it seems that the company feels a need to stand by its claims of diversity and imagination. Sort of.

Mickey and the Magical Map involves Mickey, a mapmaker’s apprentice, trying to fill in an unfinished spot on said map. The dot jumps around the world, taking Mickey to the locations of several Disney films. After King Louie finished telling the audience how much he wanted to be like us, the dot took Mickey to the setting of Pocahontas… and Mulan… and Tangled… simultaneously. Having seen only a few items of merchandise featuring Mulan and absolutely no mention of her otherwise, I was willing to ignore the seeming collapse of time and space in order to hear “Reflection,” one of my all-time favourite Disney songs. Then Rapunzel and Flynn showed up, and both Mulan and Pocahontas were suddenly incorporated into a love song and lost in a sea of lanterns. Mickey’s final destination was Hawaii, where Stitch appeared without Lilo or Nani, despite the fact that they, and not he, are native to the area. It’s a bit of a mess, and it proves that even in a show intended to illustrate Disney’s diversity, they still prefer to feature the popular characters that are already featured elsewhere.

Yet I found that some of my favourite memories of the trip came as a result of Disney’s marketing machine. All around the park, I saw hundreds of little girls wearing princess costumes. Those who wore Tiana’s outfit reminded me that, despite the film’s flaws, Tiana herself is worth looking up to. One particularly memorable group of girls stood in front of me in the line to meet Merida, each one sporting dyed red hair and an official dress, clearly excited to meet their favourite character. I myself made a Build-a-Bear and named her after the princess of the Clan Dunbroch.

My favourite memory, however, is of standing in the audience for World of Color, watching scenes from the films of my childhood, when suddenly there was the image of a red-haired girl and dozens of little voices exclaiming, “Merida!” As an adult, I connected to Merida immediately, but I found her more compelling the more profoundly I considered the critical work being performed by her story. Hearing a bunch of kids express such utter joy at seeing her made me remember what it was like to love Belle, simply because she was awesome. Like the older brother said in that commercial, it really brought out the kid in me.