RAMONA FLOWERS

AMERICAN NINJA DELIVERY GIRL

AGE UNKNOWN

EVERYTHING UNKNOWN

FUN FACT: UNKNOWN

Ramona Flowers is American. Ramona Flowers is the girl of Scott Pilgrim’s dreams, literally. Ramona Flowers is a mystery, wrapped in an enigma, wrapped in a conundrum, all surrounding a squishy, straightforward centre: a Tootsie Roll Pop of characterization. And if Scott Pilgrim is the lens through which the story is told, Ramona Flowers is its focal point.

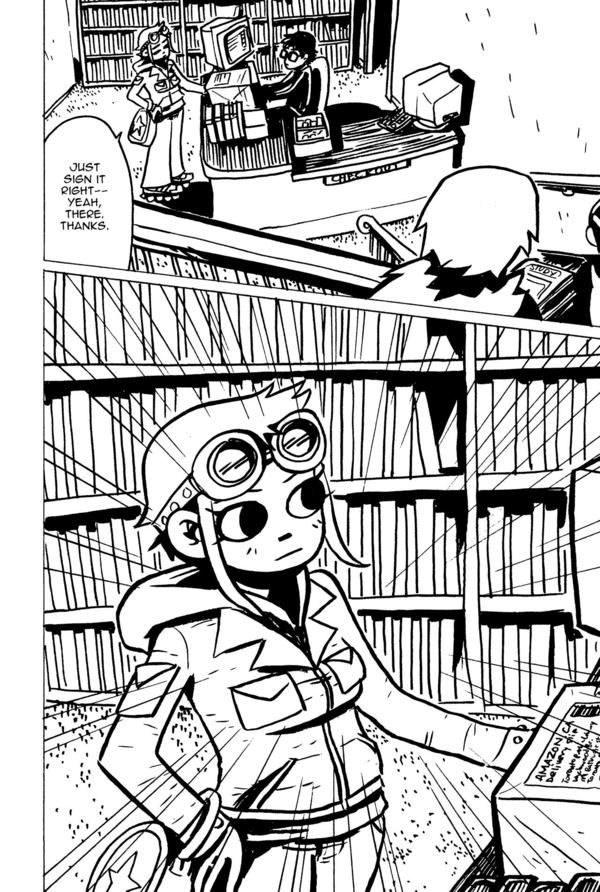

When she first enters the story, rollerblading across an arid desert of loneliness, Ramona seems like she will be no more than one more in a long line of Manic Pixie Dream Girl characters. The MPDG is a term coined in 2005 to describe a young, spirited woman who is so high on life that she must drag the male protagonist along for the ride, turning his boring life upside down and giving him the motivation he previously lacked.

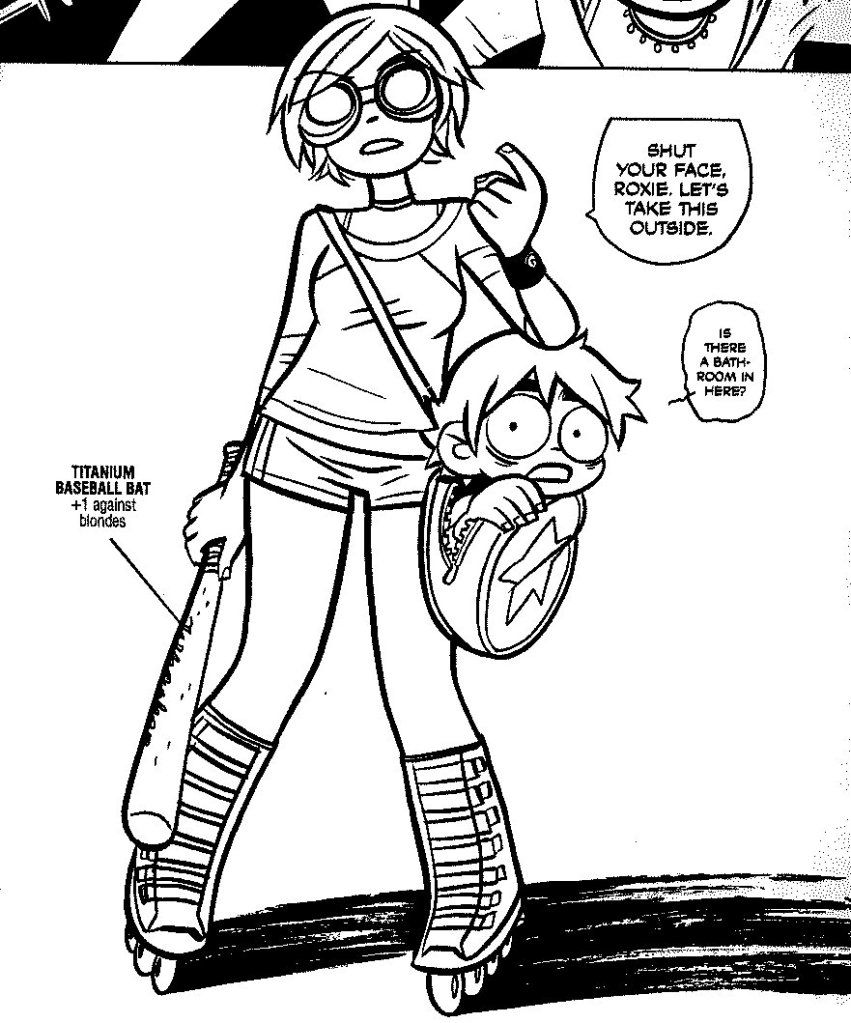

Like many a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, Ramona is introduced as the solution to the male protagonist’s dull, static existence. She is quirky, intelligent, and ever-changing. Unlike the typical MPDG, however, Ramona clearly has an existence outside the protagonist’s limited world. Her mysterious allure is less the result of a personality tailored to the needs of the hero than a simple matter of the hero not taking an interest in learning about her. The MPDG trope is brutally taken to account when Scott and Ramona have a discussion about what attracts each of them to the other. Scott claims to like Ramona because she is mysterious, and Ramona quite understandably thinks that that’s not enough and that he should know more about her like, say, her age. When he replies that it’s unknown, as if that’s a valid excuse, she responds by saying that he could just ask. In this moment, Ramona introduces the idea that she is not a mystery forever resisting a solution, but an actual person with whom Scott could interact on a human level.

Because the series is so thoroughly based in Scott’s subjective viewpoint, it makes sense that the reader comes to know Ramona just as Scott does. In the first volume, Ramona is introduced as a prize, and objects have no need of a personality. In order to win her, Scott must defeat her seven evil exes in a series of increasingly difficult boss battles. What is particularly interesting is that Matthew Patel, the first evil ex, emails Scott before Ramona has expressed any interest in him; he begins the path toward winning Ramona even before she has consented to being won.

One of the great accomplishments of the series lies, then, in the paradigm shift from viewing a woman as an object to be won to accepting her as a whole person with agency and subjectivity; this is the development from apparent Manic Pixie Dream Girl to Actual Strong Female Character. Ramona is not perky, upbeat, or fun-loving; rather, she is sarcastic and brutally honest, encouraging Scott to grow up and take responsibility for himself instead of luring him out into the world through the sheer force of her frenetic energy. Despite her use of subspace travel, she is not some sort of otherworldly being. In fact, the text goes to great lengths to point out similarities between Scott and Ramona, from their propensity for cheating to their selfishness to their decision to take wilderness sabbaticals following their break-up. Just as Scott turned to video games to escape from his problems, Ramona, who had intended to work through her own issues, “just ended up sleeping all day, dicking around on the Internet and watching every episode of The X-Files.” In that moment, she may have become the most relatable character in the series.

Although she resembles Scott in certain ways, she exists outside of him. Like Princess Kida, it seems like we meet Ramona part way through her own story: a comic already in progress that just happens to crossover with the one that we’re reading. She has an extensive backstory involving her seven evil exes (and at least one non-evil one) delivered in intriguing, if sometimes frustratingly brief, snippets. She also has her own friendship with Kim, based on their mutual hatred of idiocy. By the third volume, Ramona turns the quest narrative on its head by taking her own shot at defeating an evil ex: Scott’s former girlfriend Envy Adams. At this point, Scott temporarily becomes a prize. Ramona further subverts the narrative by fighting Roxie, her fourth ex, in a sense fighting the battle for her self (and shooting for her own hand).

In the fifth volume, Ramona gains some autonomy from Scott’s point of view, achieving a kind of temporary subjectivity. She has a series of introspective moments, the most revealing of which occurs, conveniently, as she tries on clothing while shopping. In the two-page scene, she is clearly dissatisfied with herself; no outfit seems to work, so she tries to adjust her hair, and finally takes refuge in her hood. Throughout the scene, we see both her and her reflection but, while at first we mainly see her, as the scene goes on, we see more and more of the reflection and less and less of the person. The fact that Ramona ultimately decides to hide her hair -- her most distinctive feature -- is telling. Bryan Lee O’Malley has stated on his blog that Ramona changes her hair to try on different identities, depending on the emotional state that she is in. Covering it, then, suggests that she cannot face any version of herself.

This finally changes in the final book. The sixth volume marks the moment when Scott comes into his own as a person aware of other people; accordingly, it also contains Ramona’s crowning moments of character development. After a long absence, Ramona re-enters the story at the end of all things... or, at least, the end of Scott. This entrance directly echoes her first one, but this is definitely not the same Ramona. She observes in a candid moment, “Yes, I’m selfish. I’ve dabbled in being a bitch. But listen... I came back because... because I’m always the one who leaves. I could never say goodbye. I don’t want to be that person anymore. So... I’m sorry, Scott. I came back to say I’m really really sorry.” She does come back for herself, but explicitly in order to make a better version of herself.

In a series that revolves around the battle for Ramona, the best moments occur when she takes an active role in the fight. In this final showdown, we learn that Ramona has made a habit of beating Gideon at his own game. The bizarre glow that allowed her to disappear was originally invented as a form of imprisonment; Gideon states that it “seals you inside your head. Just you and your issues. And once you’re hit, that’s it. No cure. It’s chronic. … But this brilliant self-hater, she found a way to turn it to her advantage...” Ramona transforms these mental shackles into a form of liberation, using the glow as a way to access subspace.

When she is imprisoned in the all too literal -- if technically figurative -- shackles Gideon forces her to wear in her head, Ramona frees herself, telling Gideon, “You know, you’re right. Part of me does still belong to you. But the other parts of me... are finished with you!” A league entirely comprised of versions of Ramona that we have seen throughout the series appears to back her up as she banishes Gideon from her head, forever answering the question, “You and what army?” As if that weren’t enough, she then blocks the blow that would kill Scott using her subspace suitcase, literally and figuratively shedding her baggage. Finally, she gains the Power of Love, just as Scott did in Volume 4, and teams up with him to take down Gideon with simultaneous slices. Ramona is just as much a hero as Scott.

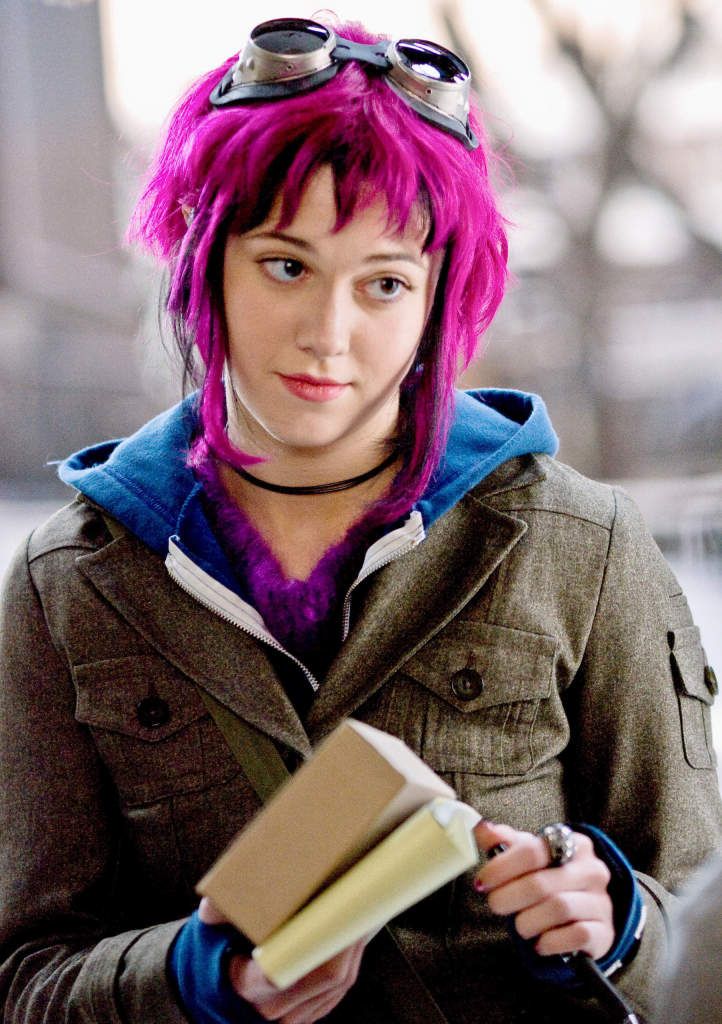

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the film version. Changes must be made when adapting six books into one movie, but it’s still unfortunate that Ramona’s characterization loses so much in the translation. Movie Ramona is a far more straightforward Manic Pixie Dream Girl. She goes back to Gideon because she “can’t help [her]self around him.” He has a way of getting into her head, and that way is a microchip, apparently. (Neither its presence nor its shutdown is really explained.) She steals Envy’s shining moment, kicks Gideon in the groin, takes a beating for her troubles, and then spends the final battle looking on as Knives teams up with Scott to beat Gideon. Knives encapsulates all the problems with this version in one line: “You’ve been fighting for her all along.”

The Ramona of the comic fights for herself. There’s a big difference between being a sprite on a screen and the person playing the game, and we’ll always side with the woman holding the controller.

Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character (comic) and Love Interest (film)

" and then spends the final battle looking on as Knives teams up with Scott to beat Gideon. " That's because Scott and Knives were originally supposed to hook up in the film, and Ramona was supposed to go off on her own. But then Book Six came out and the film ending changed so Scott goes with Ramona instead

ReplyDelete