|

| George Perez |

Dear readers,

We just want to remind you that March is Reader Appreciation Month, an opportunity for us to say thank you and for you to give us your opinion about the characters you love. While we welcome you to sit back and enjoy the posts, we need your help to make this happen. If you want to request a character for us to analyze, leave a comment on this post. If you want to write a paragraph or two telling us about your favourite female comic book character, send us an email. We'll post your messages during the weekend of the Emerald City Comicon (March 1-3). This blog could do with some more voices; make yours heard!

Sincerely,

The Management

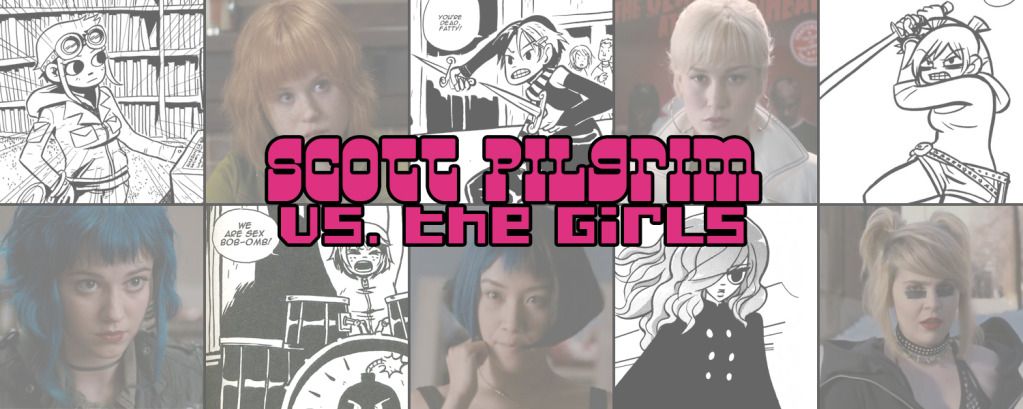

In

a series that unfolds like a video game, we would be remiss if we

didn’t discuss the boss battles. By this, of course, we mean the evil

exes.

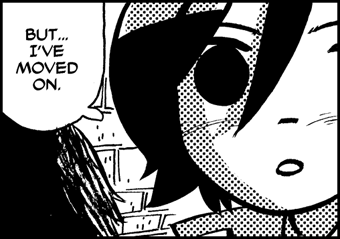

Envy Adams

If you ask Wallace Wells, Envy Adams is pure evil. If you ask Scott Pilgrim, she is a heartbreaker. No one really asks her who she is.In

Natalie V. “Envy” Adams, Bryan Lee O’Malley traces the rise of a

superstar and the fall of a fairly decent human being. When we meet

Natalie in a flashback, she is an anime fangirl who wears baggy hoodies

and dislikes parties. Over the course of her relationship with Scott,

she gives up her fannish obsessions, selling her prized possessions for

clothing and accessories; changes her name; stops remembering

relationship milestones; doesn’t bother hiding her probable cheating;

and makes all the decisions for the band they started with Stephen

Stills, even forcing Scott to switch instruments. Hers is a classic

transformation for the sake of money, fame, and power.Well,

money, fame, power, and a guy. Envy appears to be yet another example

of what can go wrong when a woman builds her life around a man. She is

completely devoted to Todd, and this makes her blind to his flaws and

his transparent lies. She believes that his gesture of love -- punching a

hole in the moon -- demonstrates an equal devotion. She believes that

gelato is vegan, because Todd says so. Even after she has discovered his

infidelity, she believes on some level that Todd didn’t deserve to be

defeated. Finally, in the scene in which she departs from Toronto, we

catch a glimpse of Natalie, once again clad in a hoodie, taking this

opportunity to remake herself without a male influence.Except,

of course, that she doesn’t. The next time we see her, she is preparing

to debut her solo album under the watchful eye of Gideon Gordon Graves,

Ramona’s seventh and most evil ex. She is intensely fetishized, as he

mentions his tendency to dress her up like a Barbie in order to achieve

sexual fulfillment. She has been reduced from a woman in control,

determining the conditions for Todd and Scott’s battles, to a sparkling

bauble for Gideon to play with. It’s

difficult to resist the symbolism that emerges in these last few

moments with Envy. Gideon has dressed her in a butterfly outfit, as if

to represent metamorphosis and flight. However, he literally removes her

wings in order to get to the sword he concealed in her outfit, leaving

her in a “sexier dress.” She is clearly reduced to a mere object.

Bizarrely, though, by the end of the final battle, she is once again

left on her own, and she retains some form of power; using her song, she

releases the six potential girlfriends Gideon had locked away. It’s a

strange moment, because it seems like Envy’s selfish need to perform

nevertheless has positive consequences.This

is one of the problems with Envy: she is difficult to figure out. She

has a shifting identity, being both Natalie and Envy to varying degrees

throughout the series. The one thing that is clear about Envy is that

our view of her is clouded by Scott’s perception. She has the power to

literally make him fall to pieces. For the duration of her first phone

call with Scott since their break-up, the visual style of the comic

changes. Suddenly, the page assumes a fragmented appearance, with

smaller panels in a 3x3 format depicting Scott’s memories of Envy

interspersed with the scattered pieces of his body, separated by the

gutters between panels. His self is actually torn apart.

So

it’s hard to consider his point of view to be objective when it comes

to Envy. In the sixth volume, Envy says as much: “You make me out to be

some kind of villainess. We were practically kids when we dated, Scott, and it’s not like you

were some paragon of virtue.” She claims that Scott broke her heart,

just as she broke his, and reminds him that he was the one who started

that final argument. Scott needed not to be the bad guy in their

relationship, so he made Envy suit the role.

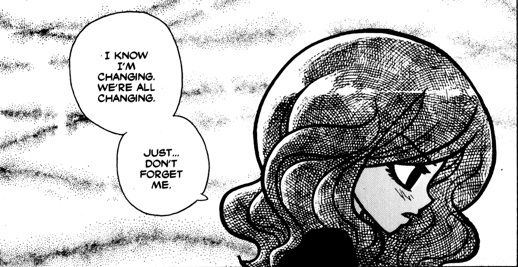

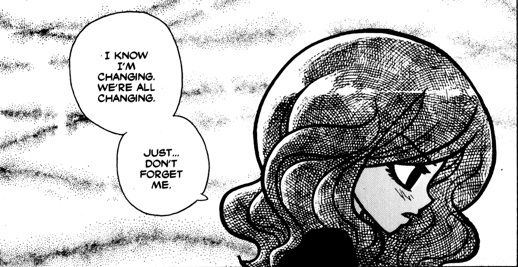

The

concept of perception is further complicated by a statement Envy makes

at the end of this conversation: “I know I’m changing. We’re all

changing. Just... don’t forget me. This is the only me he

knows...” This is an issue that goes beyond the problematic aspects of

Scott’s suffocating perception that we brought up in our discussion of

Kim. Guilty of papering over real events with his more convenient

memories, Scott is being entrusted with the preservation of Natalie V.

Adams. He must keep an entire person alive.

So

it’s hard to consider his point of view to be objective when it comes

to Envy. In the sixth volume, Envy says as much: “You make me out to be

some kind of villainess. We were practically kids when we dated, Scott, and it’s not like you

were some paragon of virtue.” She claims that Scott broke her heart,

just as she broke his, and reminds him that he was the one who started

that final argument. Scott needed not to be the bad guy in their

relationship, so he made Envy suit the role.

The

concept of perception is further complicated by a statement Envy makes

at the end of this conversation: “I know I’m changing. We’re all

changing. Just... don’t forget me. This is the only me he

knows...” This is an issue that goes beyond the problematic aspects of

Scott’s suffocating perception that we brought up in our discussion of

Kim. Guilty of papering over real events with his more convenient

memories, Scott is being entrusted with the preservation of Natalie V.

Adams. He must keep an entire person alive.

What

troubles us -- and what we’re pretty sure is supposed to trouble us --

about this line is the way it frames and genders memory. Scott’s story

involves him having to look beyond his own straight, white, male

narrative in order to acknowledge the truth of other viewpoints. What

are the implications, then, of Envy entrusting him with her self before

he has seen the error of his ways? Indeed, what are the implications of

allowing a woman’s identity to be maintained or determined by a man? In

addition, it’s problematic not only that Scott is made responsible for

Natalie, but that Gideon is seemingly creating Envy. Scott is therefore

protecting her past self from Gideon’s controlling influence. Unlike

Ramona, who finds a way to save herself using an army of Ramonas, Envy

is defined by men.It

almost seems disingenuous to mention the film version here, because

she’s nothing more than a caricature. She doesn’t even get to fight. She

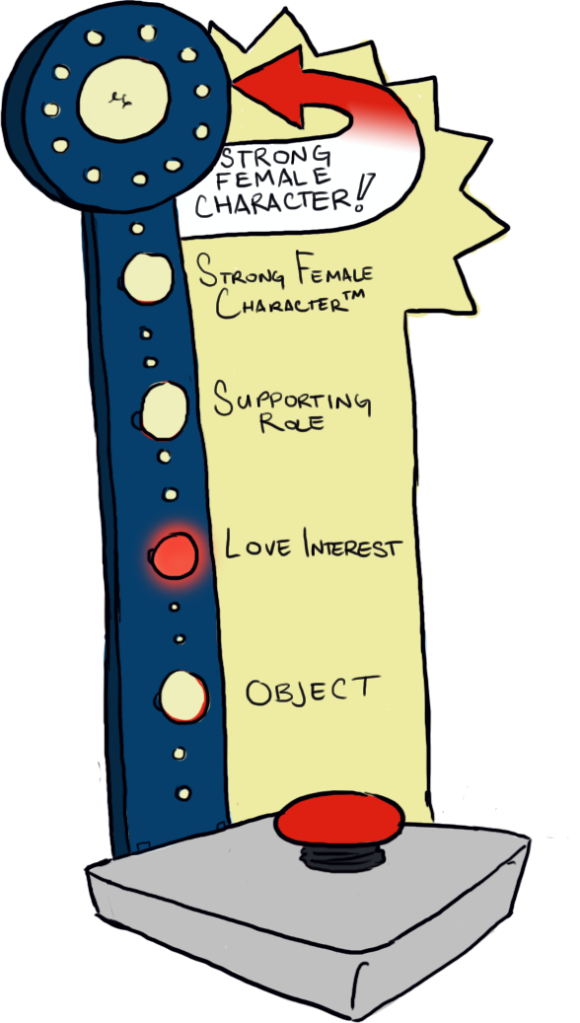

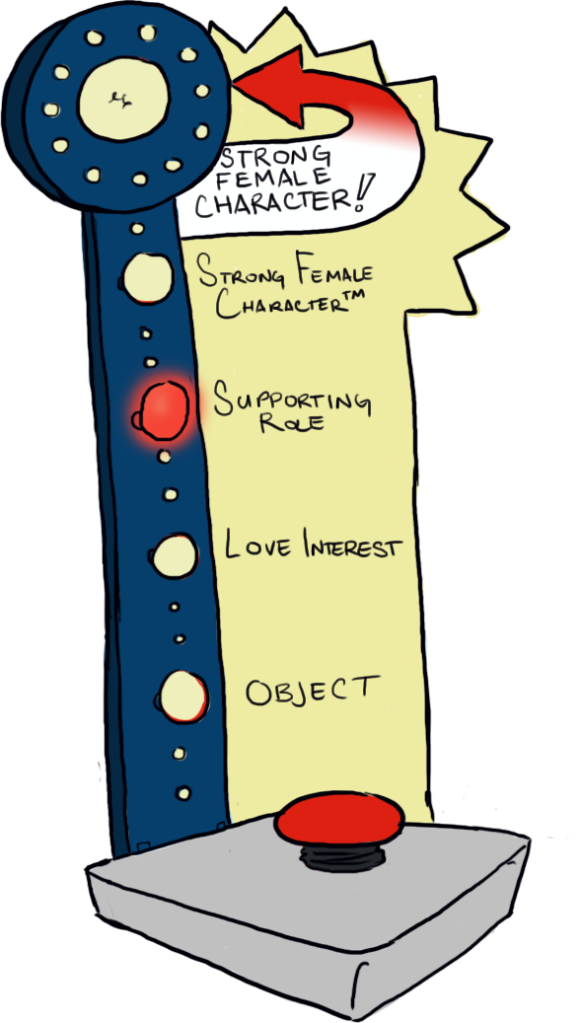

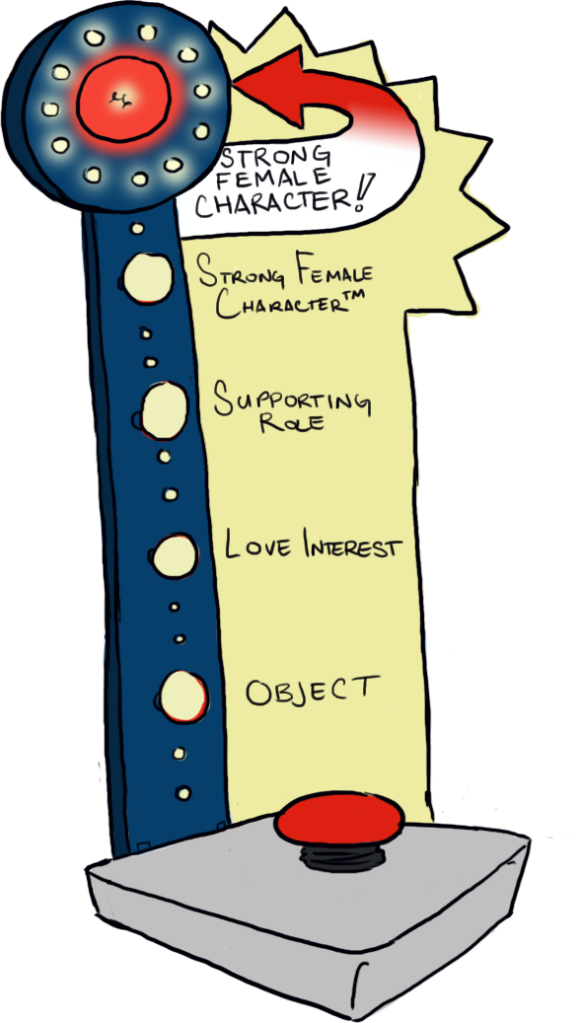

does, however, get to rock a Metric song.Verdict: Love Interest

What

troubles us -- and what we’re pretty sure is supposed to trouble us --

about this line is the way it frames and genders memory. Scott’s story

involves him having to look beyond his own straight, white, male

narrative in order to acknowledge the truth of other viewpoints. What

are the implications, then, of Envy entrusting him with her self before

he has seen the error of his ways? Indeed, what are the implications of

allowing a woman’s identity to be maintained or determined by a man? In

addition, it’s problematic not only that Scott is made responsible for

Natalie, but that Gideon is seemingly creating Envy. Scott is therefore

protecting her past self from Gideon’s controlling influence. Unlike

Ramona, who finds a way to save herself using an army of Ramonas, Envy

is defined by men.It

almost seems disingenuous to mention the film version here, because

she’s nothing more than a caricature. She doesn’t even get to fight. She

does, however, get to rock a Metric song.Verdict: Love Interest

Roxie Richter

If

we’re discussing the ex who most influenced Scott, we have to talk

about the ex who, aside from Gideon, had the greatest influence on

Ramona.

Roxie Richter affects the story even before she is introduced. In the world of Scott Pilgrim,

male homosexuality has always existed, in the form of Wallace Wells,

his boyfriend, Mobile, the Other Scott, Kim’s roommate, Joseph, and, at

the last possible second, Stephen Stills. Queer female sexuality,

however, doesn’t warrant a mention until the fourth volume, when it is

suddenly EVERYWHERE. Kim and Knives have a drunken make-out session, and

Ramona starts to make comments about marrying Kim. Wallace tells Scott

to break out the “L” word, to which Scott responds, “Lesbian?” It seems

almost as if O’Malley thought he needed to remind his readers that women

can be interested in other women so we wouldn’t be shocked when an

actual queer woman showed up.Roxie

is introduced as an almost invisible force, which seems somehow

appropriate when she represents a group of people heretofore invisible

in the series’ universe. We learn that the canonical reason for this is

that she is a half-ninja and therefore has a sword, as well as the

ability to move with “almost ninja-like stealth and speed.” We also

learn that Roxie and Ramona were roommates at the University of Carolina

in the Sky, a floating school tethered to a mountain by a giant chain.

Unlike any ex before her, Roxie seems to have Ramona’s number, calling

her out on her habitual cheating. At the same time, Roxie is clearly the

ex Ramona knows best, evidenced by the familiarity of their highly

personal insults.There

is a strange and unpleasant subtext in the treatment and

characterization of Roxie. She is intensely insecure, interpreting

Ramona’s comment that she’s a lousy excuse for a ninja as a slight

against her half-ninja status: “Half ain’t good enough, huh?!” When

Knives’ father shows up to fight Scott, Roxie immediately assumes that

Gideon sent him to help her. She has an emotional outburst, shouting, “I

don’t need help! Why doesn’t anyone ever believe

in me?!” Even the expository text doesn’t respect her, identifying her

as the “4th evil ex-boyfriend.” Further supporting the idea that no one

takes her seriously is the fact that, after Scott avoids every

opportunity to fight her, one time even going so far as to hide in

Ramona’s subspace suitcase, he defeats her with a single blow.It

seems to be no coincidence that she is the ex that represents a

homosexual blip in Ramona’s largely heterosexual dating history. Her

relationship with Ramona was, for Ramona, apparently just a phase. Even

when Roxie promises to kill him, Scott doesn’t consider the possibility

that she might be one of the evil exes or, indeed, the reason why Ramona

no longer refers to them as her seven evil ex-boyfriends. Instead, he

assumes that Roxie is merely dating one of the exes. The realization of

her true identity is so momentous that it requires an entire page for

Scott’s brain to literally crack open. He points a finger, almost in

accusation, and then, when Ramona says that it was only a phase, he

replies, “You had a sexy phase?!” Every other ex at this level is a serious threat, and Roxie is part of a sexy phase.

Indeed,

the book even puts forward the idea that a woman cheating on a man with

another woman isn’t actually cheating. When Ramona tries to apologize

to Scott for Roxie staying at her place, she assures him that they

“didn’t even make out that much.” This is apparently not infidelity

enough to get in the way of an exchange of love confessions.To

add insult to injury, Roxie shows up in the volume where Scott finally

gets up the nerve to tell Ramona that he loves her, thereby earning a

sword representing the Power of Love. So the heterosexual man defeats

the queer woman who dated his girlfriend with the power of heterosexual

love. This may be the absolute worst statement made in the entirety of

the series.

It’s

especially obvious that Roxie and Ramona’s relationship is invalidated

due to Roxie’s gender, as she is actually quite clearly second only to

Gideon in the extent of her effect on Ramona. Ramona’s trademark

rollerblades seem to be a riff on Roxie’s rollerskates. Roxie claims on

two occasions to have taught Ramona everything she knows about subspace.

She seems to be the only person Ramona didn’t just play with for a few

days or weeks before she got tired of them, as demonstrated by their

familiarity with each other and Ramona’s decisions to have lunch with

Roxie and visit her gallery opening.What

complicates the portrayal of Roxie in the comic is, as always, the fact

that we are still by the fourth volume quite firmly entrenched in

Scott’s point of view. His heteronormative viewpoint may be affecting

the storytelling itself. This seems unlikely, however, because most of

the instances where Scott’s perspective has a profound effect are

interrogated in some way. This is played pretty straight. (Pun

intended.)What

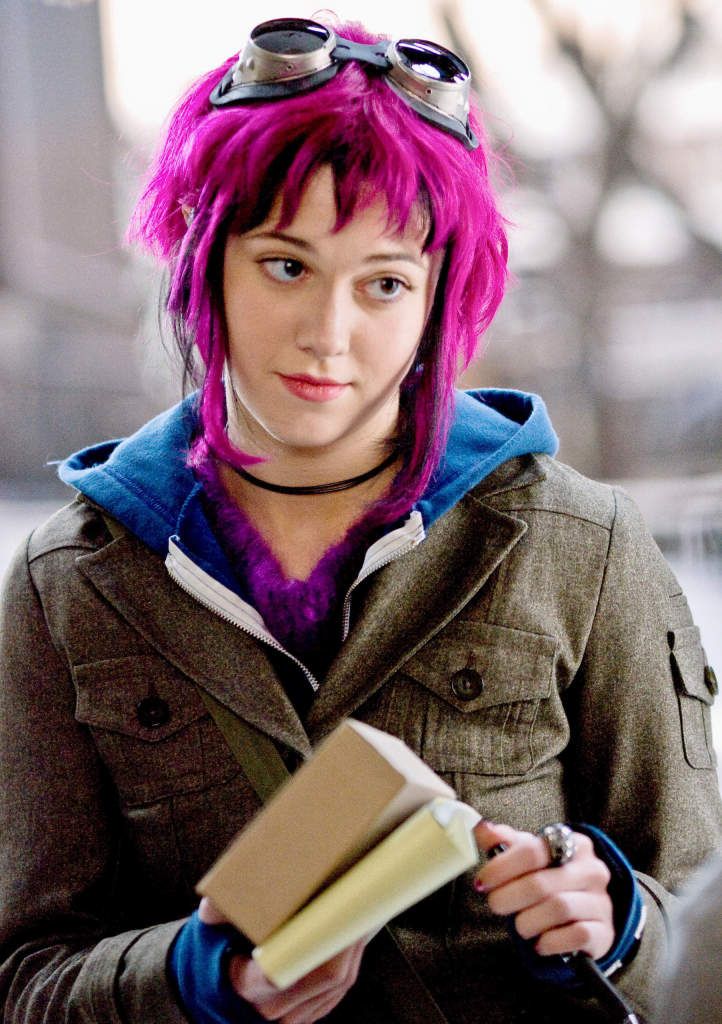

is also played pretty straight is the film’s rendition of the Scott vs.

Roxie battle. We’ve talked in every post in this series about the

injustices done to the female characters in their translation from page

to screen. In a lot of ways, it may have been more apt to call this

series “Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World Vs. the Girls.” Still, no female character’s arc becomes more thoroughly offensive than Roxie’s.Roxie,

or Roxy, as she’s apparently called in the film, is introduced almost

exactly as she is in the comic. Her defeat, however, could not be more

different. This is partially because in the original, it’s not actually

her battle, but rather one that takes place between Ramona and Envy. The

battle begins when an invisible Roxy punches Scott in the back of the

head and knocks him to the ground. As he sits up, we’re given a

delightful view of him framed by Roxy’s legs, just to demolish any hope

you may have had that Roxy was going to be treated as seriously as the

other exes.This

becomes even clearer when Ramona tells Scott not only that her

relationship with Roxy was a phase, but that “it meant nothing. I didn’t

think it would count! … I was just a little bicurious.” As if this

weren’t bad enough, the soundtrack for the reveal that Roxy is one of

the evil exes is punctuated with breathy feminine sighs.

Roxie Richter affects the story even before she is introduced. In the world of Scott Pilgrim,

male homosexuality has always existed, in the form of Wallace Wells,

his boyfriend, Mobile, the Other Scott, Kim’s roommate, Joseph, and, at

the last possible second, Stephen Stills. Queer female sexuality,

however, doesn’t warrant a mention until the fourth volume, when it is

suddenly EVERYWHERE. Kim and Knives have a drunken make-out session, and

Ramona starts to make comments about marrying Kim. Wallace tells Scott

to break out the “L” word, to which Scott responds, “Lesbian?” It seems

almost as if O’Malley thought he needed to remind his readers that women

can be interested in other women so we wouldn’t be shocked when an

actual queer woman showed up.Roxie

is introduced as an almost invisible force, which seems somehow

appropriate when she represents a group of people heretofore invisible

in the series’ universe. We learn that the canonical reason for this is

that she is a half-ninja and therefore has a sword, as well as the

ability to move with “almost ninja-like stealth and speed.” We also

learn that Roxie and Ramona were roommates at the University of Carolina

in the Sky, a floating school tethered to a mountain by a giant chain.

Unlike any ex before her, Roxie seems to have Ramona’s number, calling

her out on her habitual cheating. At the same time, Roxie is clearly the

ex Ramona knows best, evidenced by the familiarity of their highly

personal insults.There

is a strange and unpleasant subtext in the treatment and

characterization of Roxie. She is intensely insecure, interpreting

Ramona’s comment that she’s a lousy excuse for a ninja as a slight

against her half-ninja status: “Half ain’t good enough, huh?!” When

Knives’ father shows up to fight Scott, Roxie immediately assumes that

Gideon sent him to help her. She has an emotional outburst, shouting, “I

don’t need help! Why doesn’t anyone ever believe

in me?!” Even the expository text doesn’t respect her, identifying her

as the “4th evil ex-boyfriend.” Further supporting the idea that no one

takes her seriously is the fact that, after Scott avoids every

opportunity to fight her, one time even going so far as to hide in

Ramona’s subspace suitcase, he defeats her with a single blow.It

seems to be no coincidence that she is the ex that represents a

homosexual blip in Ramona’s largely heterosexual dating history. Her

relationship with Ramona was, for Ramona, apparently just a phase. Even

when Roxie promises to kill him, Scott doesn’t consider the possibility

that she might be one of the evil exes or, indeed, the reason why Ramona

no longer refers to them as her seven evil ex-boyfriends. Instead, he

assumes that Roxie is merely dating one of the exes. The realization of

her true identity is so momentous that it requires an entire page for

Scott’s brain to literally crack open. He points a finger, almost in

accusation, and then, when Ramona says that it was only a phase, he

replies, “You had a sexy phase?!” Every other ex at this level is a serious threat, and Roxie is part of a sexy phase.

Indeed,

the book even puts forward the idea that a woman cheating on a man with

another woman isn’t actually cheating. When Ramona tries to apologize

to Scott for Roxie staying at her place, she assures him that they

“didn’t even make out that much.” This is apparently not infidelity

enough to get in the way of an exchange of love confessions.To

add insult to injury, Roxie shows up in the volume where Scott finally

gets up the nerve to tell Ramona that he loves her, thereby earning a

sword representing the Power of Love. So the heterosexual man defeats

the queer woman who dated his girlfriend with the power of heterosexual

love. This may be the absolute worst statement made in the entirety of

the series.

It’s

especially obvious that Roxie and Ramona’s relationship is invalidated

due to Roxie’s gender, as she is actually quite clearly second only to

Gideon in the extent of her effect on Ramona. Ramona’s trademark

rollerblades seem to be a riff on Roxie’s rollerskates. Roxie claims on

two occasions to have taught Ramona everything she knows about subspace.

She seems to be the only person Ramona didn’t just play with for a few

days or weeks before she got tired of them, as demonstrated by their

familiarity with each other and Ramona’s decisions to have lunch with

Roxie and visit her gallery opening.What

complicates the portrayal of Roxie in the comic is, as always, the fact

that we are still by the fourth volume quite firmly entrenched in

Scott’s point of view. His heteronormative viewpoint may be affecting

the storytelling itself. This seems unlikely, however, because most of

the instances where Scott’s perspective has a profound effect are

interrogated in some way. This is played pretty straight. (Pun

intended.)What

is also played pretty straight is the film’s rendition of the Scott vs.

Roxie battle. We’ve talked in every post in this series about the

injustices done to the female characters in their translation from page

to screen. In a lot of ways, it may have been more apt to call this

series “Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World Vs. the Girls.” Still, no female character’s arc becomes more thoroughly offensive than Roxie’s.Roxie,

or Roxy, as she’s apparently called in the film, is introduced almost

exactly as she is in the comic. Her defeat, however, could not be more

different. This is partially because in the original, it’s not actually

her battle, but rather one that takes place between Ramona and Envy. The

battle begins when an invisible Roxy punches Scott in the back of the

head and knocks him to the ground. As he sits up, we’re given a

delightful view of him framed by Roxy’s legs, just to demolish any hope

you may have had that Roxy was going to be treated as seriously as the

other exes.This

becomes even clearer when Ramona tells Scott not only that her

relationship with Roxy was a phase, but that “it meant nothing. I didn’t

think it would count! … I was just a little bicurious.” As if this

weren’t bad enough, the soundtrack for the reveal that Roxy is one of

the evil exes is punctuated with breathy feminine sighs.

When

Roxy then tries to attack Scott, Ramona intervenes; in this version,

she doesn’t fight Roxy because Scott is hiding behind the rules of

chivalry and his own terror, but because she just... does? It’s not

explained. Roxy also suddenly fights with a whip-sword-belt-thing

because, I don’t know, it’s sexier than a sword or something. (The

change is likely a matter of increasing visual interest and avoiding

repetition in a film where the final battle involves swords, but

still...) When Roxy reveals that Scott will have to defeat her by his

own hand, he protests, saying that he can’t hit a girl. Instead of

denying Scott the moral high ground he thinks he deserves for taking

this position, as Ramona and Roxie both do in the book, Ramona just

tells him that he has no choice... and then proceeds to control his

limbs as he enters into fisticuffs with Roxy. Then

something happens that makes us a little bi-furious. As Roxy lifts her

leg in the air to deliver the final blow, Ramona tells Scott that Roxy’s

weakness is an erogenous zone at the back of her knee. This will be

familiar to readers of the comic as Envy’s weakness, discovered by Scott

during a serious two-year relationship, and used to take her down in a

non-lethal manner. In the movie, however, it is a weakness discovered

during just-for-fun make-out sessions, used by a straight man to orgasm a

queer woman to death. Roxy’s last words: “You’ll never be able to do

this to her,” followed by a blissful moan. Our reaction: not suitable

for print.What

really irks us about this scene is that it is so intentional. Roxy

suffers a perfectly adequate, if still dubious, defeat in the comic, so

the appropriation of Envy’s fight and weakness represents a deliberate

change. A character that is already treated as a joke is humiliated in

an incredibly offensive way, and we’re supposed to find it funny. We

are, perhaps, even supposed to think it better than the original. We’re

actually not sure what could have been worse.Verdict: Love Interest (Comic) and NO NO NO OH GOD WHY (Film)

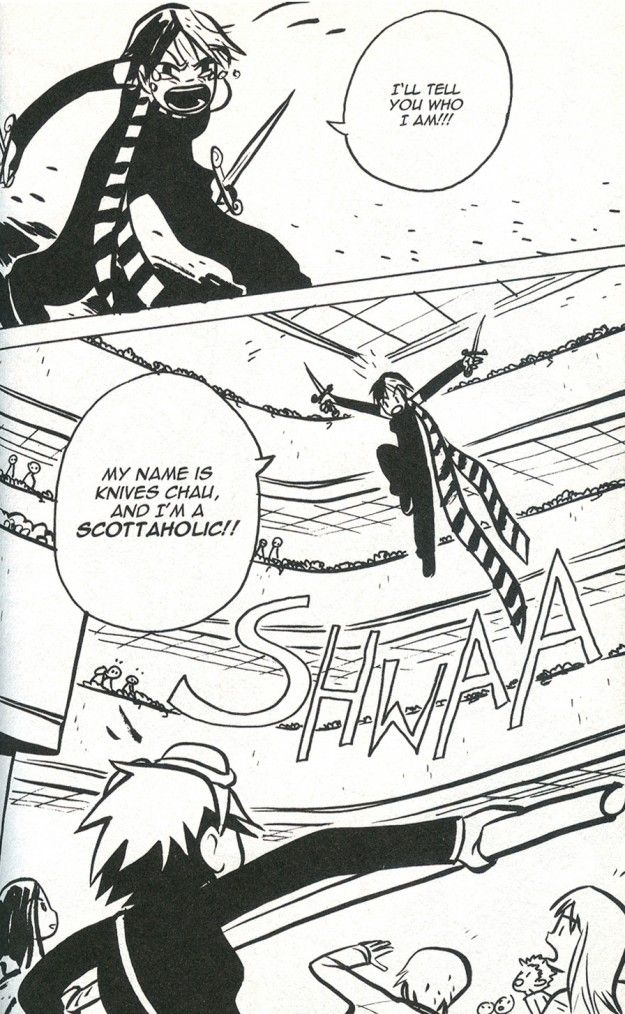

KNIVES CHAU17 YEARS OLDSTATUS: TOTALLY CRAZY

“Scott

Pilgrim is dating a high schooler!” So begins the tale of Scott

Pilgrim, introducing at the same moment its titular character and his

seventeen-year-old counterpart, Knives Chau.Knives

enters the story as a stereotypical Asian teenager, complete with

overbearing parents and advanced textbooks. She initially treats Scott

as another friend, regaling him with stories of high school drama. Their

relationship is almost preternaturally innocent, and it is only after

she hears Sex Bob-omb play for the first time that her obsession with

Scott truly takes hold. Hearing those poorly played chords pitches her

face first onto the Yellow Brick Road to adulthood; though her world as

we see it remains a land of black and white, she has clearly had her

first glimpse of Technicolor.For

Kim, music is a constant, structuring her life; for Knives, it is a

gateway to emotions and situations she has never before had a chance to

experience. When Scott starts dating Ramona, Knives bemoans her relative

lack of life experience: “She’s had time, you know?? She’s got a head

start! What am I supposed to do?? How do I fight that? I didn’t even

know there was

good music until like two months ago!!” Knives frames what she seems to

think of as a kind of life seniority in terms of music knowledge, as if

everyone had an equally melodic moment of maturation. Her

discovery of music also coincides with the beginning of her search for a

model of femininity to emulate. After that first rehearsal, she cuts

her hair and starts to dress like Kim. Once Scott has dumped her for

Ramona, she gets highlights, mimicking Ramona’s dye job as if that will

restore her to Scott’s favour. Although she doesn’t imitate any

particular aspect of Envy’s style, she does become obsessed with her,

not only explicitly calling her her role model, but also freaking out

over the idea that she’s kissed the lips that have kissed Envy. She even

tells Scott that he’ll “always be [her] Clash at Demonhead,”

compounding in one sentence her love of Scott, her obsession with Envy,

and her devotion to music.This

is not to say that Knives’ attitude toward other women is at all

positive or healthy. For the majority of the series, she views Ramona as

the harlot who stole her man while refusing to see Scott for the cad he

demonstrably is. She is constantly using gender-based insults like

“slut” and often stoops to calling other women “ugly” or “fat,”

regardless of evidence for either claim. Accordingly,

most of Knives’ characterization revolves around her being herself a

kind of two-dimensionally awful woman. She is the Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

who becomes a stalker and picks fights with her ex’s current love

interest, asserting throughout that she’s a “Scottaholic.” She dates

Young Neil because he looks like Scott. She even has a shrine. In a

narrative that revolves around Scott, she becomes proof of the damage a

Scott-centred existence can do.

She

is also, in many ways, a reflection of Scott. His dating her represents

a regression, as he turns to the easy world of teenage dating to avoid

the realities of adulthood. Over the course of the series, he must grow

up and learn to take responsibility for his own actions, learning that

life isn’t a video game, even if he appears to be living in one. Knives

undergoes a more straightforward, if less thoroughly explored,

coming-of-age story. She is introduced as a shy, naive child who begins a

musically triggered metaphorical puberty. By the third volume, she is

beginning to understand the double-edged sword that is adulthood: “I

mean, I’m not totally happy, but there’s no way I’d go back to my old

oblivious self! I like it here. I like all the... confusion and

heart-break. … I feel like I’ve learned some stuff along the way. I know

things now.” Eventually, by the final book, Knives’ development has

surpassed Scott’s. She is eighteen, an adult in the eyes of the law and a

soon-to-be graduate of high school, and she has left the stalled Scott

behind. This becomes obvious when she rejects Scott’s offer of casual

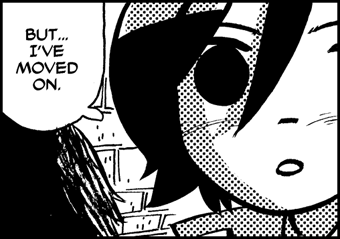

sex, telling him that they should try to be grown-ups.Her

maturity is finally demonstrated by her decision to let Scott go. He

retains the importance of being her first boyfriend as well as the

person who helped open her eyes to the world beyond her Catholic school,

but that’s all. As she asserts, “I’m happy being alone right now,

Scott. I’m trying to learn to like me. Alone.” Best ending for a character that seemed to be nothing more than a caricature of a crazy ex? We think so.

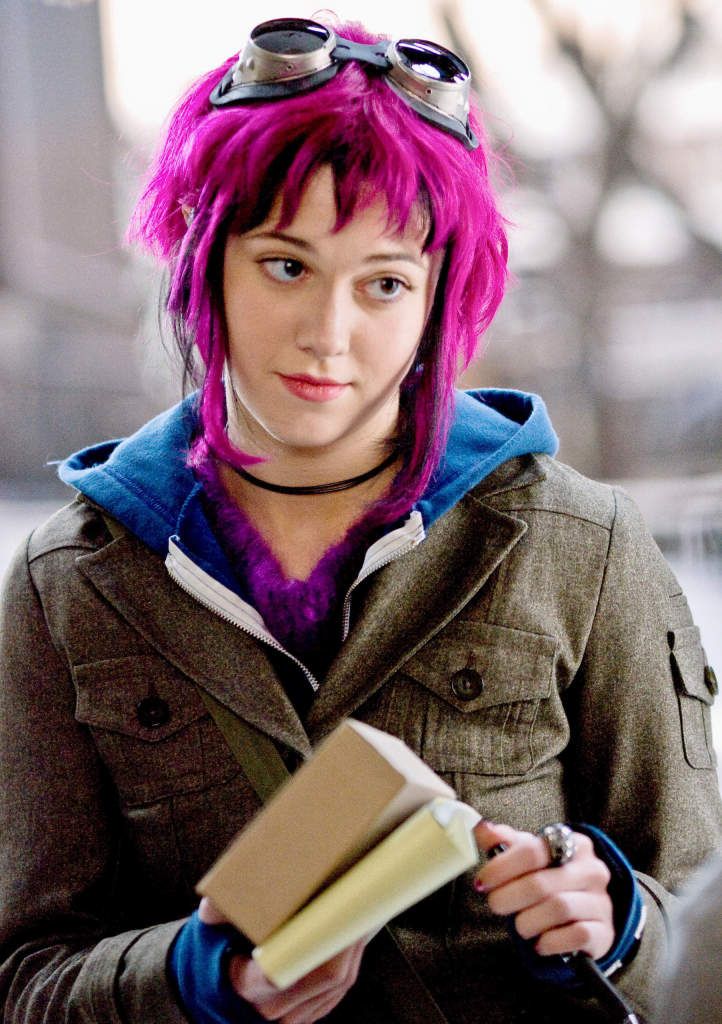

The

film’s version of Knives doesn’t fare much better than Ramona or Kim.

While she does get to replace Ramona in the final battle against Gideon,

she was only there because she wanted to fight Ramona and punish her

for stealing Scott. Whereas the comic leaves us with an image of Knives

as an independent person striking out on her own, the film ends with

Knives telling Scott to go get the girl, assuring him with a wry “I’m

too cool for you anyway.” It’s an important and disappointing

difference. Comic!Knives completes her character arc by growing up, and

leaving Scott behind is merely part of the process. Movie!Knives

completes her own arc by letting Scott go, making the romantic

relationship the whole point of her story. As you may imagine, we don’t

like this ending very much at all.Verdict: Supporting Role (Comic) and Love Interest (Film)

In the marketing for the film, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World,

Kim Pine is described as “the sarcastic one.” The movie’s two-hour

runtime demanded an all-encompassing simplification of the story from

which few characters escaped unscathed. The greatest casualty aside from

Ramona, Kim retains -- but is also ultimately reduced to -- her quick,

acerbic wit. The Kim of the film is not the Kim of the comic, but rather

the self that Comic!Kim wishes the world to see.At

first glance, Kim is a simple character: she hates everything. In fact,

she is almost relentlessly pessimistic. She never misses a chance to

talk about how much Sex Bob-omb sucks. She leaps at every opportunity to

criticize Scott. She despises everyone, including her friends.

Except,

of course, that she doesn’t. She loves music, evidenced by the

flashback in which she pauses in the middle of a back seat session with

Scott to get him to listen to the song on the radio. Although she acts

like Sex Bob-omb’s rehearsals and gigs are the worst part of her day,

she later confesses that they give her life structure and, at the end of

the series, we see that she has joined Scott’s new group, Shatterband.

Keeping time behind a drum set seems to give her some kind of control,

real or imagined, over what is revealed to be a pretty dismal existence.In

a conversation with her boss, Hollie, Kim tells her that she hates her.

“You hate everyone, Kim,” Hollie observes, prompting Kim to reply,

“You’re one of everyone.” Although this exchange is clearly intended to

be funny, there is more than a little truth to the statement, and more

than a little justification for Kim’s misanthropy. Most of the people in

her life really do suck. While Scott is too busy fighting exes to

direct our attention to her, Kim suffers a number of personal blows. She

deals with the roommates from Hell (whose antics are briefly chronicled

in a separate one-shot entitled, as ironically as humanly possible,

“The Wonderful World of Kim Pine”), before moving in with Hollie. Hollie

promptly sleeps with Kim’s boyfriend, thereby turning her home --

already the site of the recording that has disrupted the steady rhythm

of her life -- into a hostile territory. It’s not difficult to see how

Kim could claim to hate everyone.“Everyone,”

however, has some notable exceptions, among them one Ramona Flowers.

Ramona and Kim forge a friendship based on their mutual disdain for

idiocy as well as a genuine appreciation for each other. They banter

easily, but Kim knows when to give Ramona her space. The best example

occurs when Kim notices Ramona’s head glowing and decides to gather

photographic evidence in order to confront her about it. When Ramona

gets defensive, Kim backs off, saying, “If you can’t tell me, you can’t

tell me. I won’t be offended.” She tries to make Ramona see that there

is a problem, but doesn’t force her to deal with it. In a series with

numerous girl vs. girl verbal and physical smackdowns, such a friendship

is refreshing. Kim’s ability to handle Ramona also clarifies the nature

of her misanthropy: she dislikes people not because she doesn’t

understand them, but because she so clearly does, which may be the

reason why she always expects them to let her down.And

let her down they do, perhaps no one more than Scott. In the fifth

volume, while in the process of kidnapping her, the Katayanagi twins

observe that she has “been there all along,” standing beside Scott.

While she does insult him, she also encourages him; for every few digs

along the lines of “Scott, if your life had a face, I would punch it. I

would punch your life in the face,” there’s a “Come ON, Scott! You can

do this, you know. You’re not as clueless an idiot as you seem!”

Unfortunately, Scott does not offer the same support in return.

The

altercation with the Katayanagis is a defining moment for Kim, as she

is confronted with the reality of her one-sided relationship with Scott.

Still, even when she cannot convince Scott to save her for her own

sake, she helps him to defeat the twins by pretending that her

inspirational words are Ramona’s. In a way, by manipulating Scott, she

saves herself. As Kim departs at the end of the book, Scott apologizes

for everything. When Kim dismisses it, telling him it’s not his fault,

he shouts, “Sorry about me!” This is the apology that Kim can accept. Kim’s importance to Scott Pilgrim as a character is reflective of her importance to Scott Pilgrim

as a series. If Scott is the lens through which the story is told, and

Ramona is its focal point, Kim Pine is the person standing next to you,

pointing to the lens and saying, “Trust nothing it shows you.”

Throughout the series, Kim serves as a kind of bullshit detector, as she

uses her substantial powers of observation to interrogate Scott’s

version of events. She questions his decision to date a high schooler,

his validity as a hero, and, ultimately, the reliability of his

narration. Multiple characters point out the holes in Scott’s

recollections, but Kim is the person who breaks him out of his cycle of

forgetting and forces him to restore the memory of his mistakes. Her own

story literally replaces the one we already read, panels from earlier

volumes juxtaposed with new versions in a displacement of fiction by

fact. Kim is the person responsible for dismantling Scott’s subjective

narrative.

This

is why her diminished presence in the film is such a crime. The

viewer’s perception is even more closely tied to Scott’s point of view,

which is worrying on a metatextual level. In the film, the dominant

narrative isn’t questioned, whereas, in the books, the convenient lies

Scott tells himself are replaced by the truth as witnessed by those he

wronged. The film eliminates so many of the book’s more compelling ideas

about the importance of perception in storytelling. For this reason, we

would have preferred it if the girl who has “been there all along” had

actually been there in her entirety.It’s

difficult to determine where Kim falls on our scale of character

strength. She is a past love interest, as well as a supporting character

in every sense of the word. She has her own life, but we are largely

denied access to it. The life we do see technically revolves around a

man, but she has clearly decided to make a change in that respect. We’re

inclined to say that she falls somewhere between the categories of

Strong Female Character ™ and Actual Strong Female Character, but we’re

certainly open to other interpretations.Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character ™

RAMONA FLOWERS

AMERICAN NINJA DELIVERY GIRL

AGE UNKNOWN

EVERYTHING UNKNOWN

FUN FACT: UNKNOWN

Ramona

Flowers is American. Ramona Flowers is the girl of Scott Pilgrim’s

dreams, literally. Ramona Flowers is a mystery, wrapped in an enigma,

wrapped in a conundrum, all surrounding a squishy, straightforward

centre: a Tootsie Roll Pop of characterization. And if Scott Pilgrim is

the lens through which the story is told, Ramona Flowers is its focal

point.

When

she first enters the story, rollerblading across an arid desert of

loneliness, Ramona seems like she will be no more than one more in a

long line of Manic Pixie Dream Girl characters. The MPDG is a term

coined in 2005 to describe a young, spirited woman who is so high on

life that she must drag the male protagonist along for the ride, turning

his boring life upside down and giving him the motivation he previously

lacked.

Like

many a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, Ramona is introduced as the solution to

the male protagonist’s dull, static existence. She is quirky,

intelligent, and ever-changing. Unlike the typical MPDG, however, Ramona

clearly has an existence outside the protagonist’s limited world. Her

mysterious allure is less the result of a personality tailored to the

needs of the hero than a simple matter of the hero not taking an

interest in learning about her. The MPDG trope is brutally taken to

account when Scott and Ramona have a discussion about what attracts each

of them to the other. Scott claims to like Ramona because she is

mysterious, and Ramona quite understandably thinks that that’s not

enough and that he should know more about her like, say, her age. When

he replies that it’s unknown, as if that’s a valid excuse, she responds

by saying that he could just ask. In this moment, Ramona introduces the

idea that she is not a mystery forever resisting a solution, but an

actual person with whom Scott could interact on a human level.

Because

the series is so thoroughly based in Scott’s subjective viewpoint, it

makes sense that the reader comes to know Ramona just as Scott does. In

the first volume, Ramona is introduced as a prize, and objects have no

need of a personality. In order to win her, Scott must defeat her seven

evil exes in a series of increasingly difficult boss battles. What is

particularly interesting is that Matthew Patel, the first evil ex,

emails Scott before Ramona has expressed any interest in him; he begins

the path toward winning Ramona even before she has consented to being

won.

One

of the great accomplishments of the series lies, then, in the paradigm

shift from viewing a woman as an object to be won to accepting her as a

whole person with agency and subjectivity; this is the development from

apparent Manic Pixie Dream Girl to Actual Strong Female Character.

Ramona is not perky, upbeat, or fun-loving; rather, she is sarcastic and

brutally honest, encouraging Scott to grow up and take responsibility

for himself instead of luring him out into the world through the sheer

force of her frenetic energy. Despite her use of subspace travel, she is

not some sort of otherworldly being. In fact, the text goes to great

lengths to point out similarities between Scott and Ramona, from their

propensity for cheating to their selfishness to their decision to take

wilderness sabbaticals following their break-up. Just as Scott turned to

video games to escape from his problems, Ramona, who had intended to

work through her own issues, “just ended up sleeping all day, dicking

around on the Internet and watching every episode of The X-Files.” In that moment, she may have become the most relatable character in the series.

Although

she resembles Scott in certain ways, she exists outside of him. Like

Princess Kida, it seems like we meet Ramona part way through her own

story: a comic already in progress that just happens to crossover with

the one that we’re reading. She has an extensive backstory involving her

seven evil exes (and at least one non-evil one) delivered in

intriguing, if sometimes frustratingly brief, snippets. She also has her

own friendship with Kim, based on their mutual hatred of idiocy. By the

third volume, Ramona turns the quest narrative on its head by taking

her own shot at defeating an evil ex: Scott’s former girlfriend Envy

Adams. At this point, Scott temporarily becomes a prize. Ramona further

subverts the narrative by fighting Roxie, her fourth ex, in a sense

fighting the battle for her self (and shooting for her own hand).

In

the fifth volume, Ramona gains some autonomy from Scott’s point of

view, achieving a kind of temporary subjectivity. She has a series of

introspective moments, the most revealing of which occurs, conveniently,

as she tries on clothing while shopping. In the two-page scene, she is

clearly dissatisfied with herself; no outfit seems to work, so she tries

to adjust her hair, and finally takes refuge in her hood. Throughout

the scene, we see both her and her reflection but, while at first we

mainly see her, as the scene goes on, we see more and more of the

reflection and less and less of the person. The fact that Ramona

ultimately decides to hide her hair -- her most distinctive feature --

is telling. Bryan Lee O’Malley has stated on his blog that Ramona

changes her hair to try on different identities, depending on the

emotional state that she is in. Covering it, then, suggests that she

cannot face any version of herself.

This

finally changes in the final book. The sixth volume marks the moment

when Scott comes into his own as a person aware of other people;

accordingly, it also contains Ramona’s crowning moments of character

development. After a long absence, Ramona re-enters the story at the end

of all things... or, at least, the end of Scott. This entrance directly

echoes her first one, but this is definitely not the same Ramona. She

observes in a candid moment, “Yes, I’m selfish. I’ve dabbled in being a

bitch. But listen... I came back because... because I’m always the one

who leaves. I could never say goodbye. I don’t want to be that person

anymore. So... I’m sorry, Scott. I came back to say I’m really really

sorry.” She does come back for herself, but explicitly in order to make a

better version of herself.

In

a series that revolves around the battle for Ramona, the best moments

occur when she takes an active role in the fight. In this final

showdown, we learn that Ramona has made a habit of beating Gideon at his

own game. The bizarre glow that allowed her to disappear was originally

invented as a form of imprisonment; Gideon states that it “seals you

inside your head. Just you and your issues. And once you’re hit, that’s

it. No cure. It’s chronic. … But this brilliant self-hater, she found a

way to turn it to her advantage...” Ramona transforms these mental

shackles into a form of liberation, using the glow as a way to access

subspace.

When

she is imprisoned in the all too literal -- if technically figurative

-- shackles Gideon forces her to wear in her head, Ramona frees herself,

telling Gideon, “You know, you’re right. Part of me does still belong

to you. But the other parts of me... are finished

with you!” A league entirely comprised of versions of Ramona that we

have seen throughout the series appears to back her up as she banishes

Gideon from her head, forever answering the question, “You and what

army?” As if that weren’t enough, she then blocks the blow that would

kill Scott using her subspace suitcase, literally and figuratively

shedding her baggage. Finally, she gains the Power of Love, just as

Scott did in Volume 4, and teams up with him to take down Gideon with

simultaneous slices. Ramona is just as much a hero as Scott.

Unfortunately,

the same cannot be said of the film version. Changes must be made when

adapting six books into one movie, but it’s still unfortunate that

Ramona’s characterization loses so much in the translation. Movie Ramona

is a far more straightforward Manic Pixie Dream Girl. She goes back to

Gideon because she “can’t help [her]self around him.” He has a way of

getting into her head, and that way is a microchip, apparently. (Neither

its presence nor its shutdown is really explained.) She steals Envy’s

shining moment, kicks Gideon in the groin, takes a beating for her

troubles, and then spends the final battle looking on as Knives teams up

with Scott to beat Gideon. Knives encapsulates all the problems with

this version in one line: “You’ve been fighting for her all along.”

The

Ramona of the comic fights for herself. There’s a big difference

between being a sprite on a screen and the person playing the game, and

we’ll always side with the woman holding the controller.

Verdict: Actual Strong Female Character (comic) and Love Interest (film)