To celebrate our first six months at the end of February, we will be doing a month of reader appreciation.

We’ll

be kicking things off with some reader-generated content. As the first

Friday of March is also the first day of the Emerald City Comicon (which

I will be attending), we’ve decided to dedicate the entire weekend to

your picks for your favourite female, female-identifying, or genderqueer

comic book characters. Just send us an email with a paragraph or two about your favourite four-colour female and we’ll prepare a three-day comic celebration.

For

the other four Fridays in March, we’ll be writing posts based on your

requests. If you have a character you’d like to see us cover, just leave

a comment on this post. Remember, if your request isn’t written this

time ‘round, it’s probably because we already have something planned for

them.

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

Monday, 4 February 2013

Miscellaneous Mondays: The Boy Who Lived Forever (Because Girls Made It Possible)

“Fan

fiction is what literature might look like if it were reinvented from

scratch after a nuclear apocalypse by a band of brilliant pop-culture

junkies trapped in a sealed bunker. They don’t do it for money. That’s

not what it’s about. The writers write it and put it up online just for

the satisfaction. They’re fans, but they’re not silent, couchbound

consumers of media. The culture talks to them, and they talk back to the

culture in its own language.”

So argues Lev Grossman in his TIME Magazine article, “The Boy Who Lived Forever.” The piece represents an effort to lift the curtain and reveal the largely unseen world of fan creation to a mainstream audience. Grossman introduces the concepts of slash, mpreg, and alternate universes to people who have never wept bitter tears because their favourite WIP was abandoned or bemoaned the state of television because their OTP will never become canon. It is an article intended to illuminate this usually invisible realm, not in the guise of an exposé, but as a loving tribute to the symbiotic nature of narrative creation.

While the intended audience is clearly those not in the know, there’s a lot that those of us well versed in fandom can take from this article. First and foremost, it is a positive article about fanworks, with an introduction that implies that the efforts of fan creators are just as valid as the works on which they are based. It traces the history of storytelling and demonstrates both that the worship of originality is a relatively recent development and that great art has always been derivative. Grossman also recognizes that, far from being inherently inferior to the original works, fanfiction can improve upon its predecessors.

What we’re most interested in, however, is a point he makes about halfway through the article. Having established that most fan creators are women, he goes on to discuss what may very well be fanfiction’s most important function: “Diversity: the fan-fiction scene is hyperdiverse. You’ll find every race, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, age and sexual orientation represented there, both as writers and as characters. For people who don’t recognize themselves in the media they watch, it’s a way of taking those media into their own hands and correcting the picture.” It is a way in which we can appropriate the narratives that the mainstream media deems suitable to tell, and show them that our stories are equally worthy.

Many of us are familiar with the argument that, if we aren’t happy with the way things are, we should write our own stories. Unfortunately, for a whole host of economic and social reasons, it’s almost impossible for our stories to compete with the corporation-backed media. Faced with such a situation, it should come as no surprise that we have decided to repurpose these narratives to suit us. Grossman argues that fan creators “talk back to the culture in its own language;” isn’t this the best way to ensure that we’re understood?

So argues Lev Grossman in his TIME Magazine article, “The Boy Who Lived Forever.” The piece represents an effort to lift the curtain and reveal the largely unseen world of fan creation to a mainstream audience. Grossman introduces the concepts of slash, mpreg, and alternate universes to people who have never wept bitter tears because their favourite WIP was abandoned or bemoaned the state of television because their OTP will never become canon. It is an article intended to illuminate this usually invisible realm, not in the guise of an exposé, but as a loving tribute to the symbiotic nature of narrative creation.

While the intended audience is clearly those not in the know, there’s a lot that those of us well versed in fandom can take from this article. First and foremost, it is a positive article about fanworks, with an introduction that implies that the efforts of fan creators are just as valid as the works on which they are based. It traces the history of storytelling and demonstrates both that the worship of originality is a relatively recent development and that great art has always been derivative. Grossman also recognizes that, far from being inherently inferior to the original works, fanfiction can improve upon its predecessors.

What we’re most interested in, however, is a point he makes about halfway through the article. Having established that most fan creators are women, he goes on to discuss what may very well be fanfiction’s most important function: “Diversity: the fan-fiction scene is hyperdiverse. You’ll find every race, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, age and sexual orientation represented there, both as writers and as characters. For people who don’t recognize themselves in the media they watch, it’s a way of taking those media into their own hands and correcting the picture.” It is a way in which we can appropriate the narratives that the mainstream media deems suitable to tell, and show them that our stories are equally worthy.

Many of us are familiar with the argument that, if we aren’t happy with the way things are, we should write our own stories. Unfortunately, for a whole host of economic and social reasons, it’s almost impossible for our stories to compete with the corporation-backed media. Faced with such a situation, it should come as no surprise that we have decided to repurpose these narratives to suit us. Grossman argues that fan creators “talk back to the culture in its own language;” isn’t this the best way to ensure that we’re understood?

Friday, 1 February 2013

The Snow Queen

|

| Honor C. Appleton |

The subject of this first post is markedly different than the vast majority of the tales that have come to form the backbone of Western popular culture. Published in 1845, “The Snow Queen” by Hans Christian Andersen stands out from both the crowd of male-centric stories we tell today and the throng of cautionary tales starring girls and women that come to us from The Brothers Grimm. “The Snow Queen” is a story that revolves around and celebrates women, as evidenced by the fact that, of the seven sections, six are named in whole or in part after women. We are all familiar with tales in which the male hero saves the damsel in distress, and most of us are probably well-versed in the modern subversions of these stories, in which the dude in distress is saved by a heroine. What “The Snow Queen” offers us is a take on the latter before it was cool. (Consider yourself warned; that was not the last ice joke.)

|

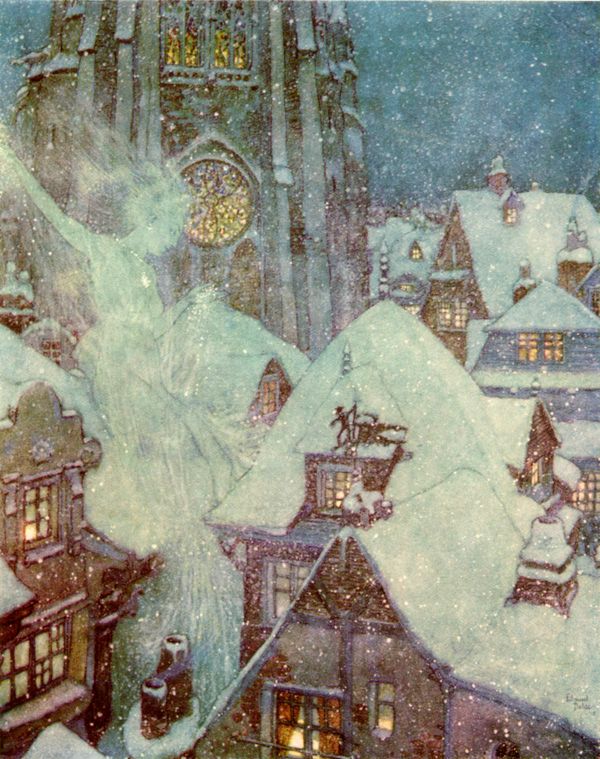

| Edmund Dulac |

This is further demonstrated in her treatment of Kay. In order to take Kay further into her realm, she kisses him twice; the first kiss stops him from feeling the cold, while the second makes him forget Gerda and the rest of his loved ones. She states, “Now you will have no more kisses... or else I should kiss you to death!” The only affection her lips can provide is frostbite, and the expression of what others might term warmth results in her victims freezing to death.

Before she becomes a hero, Gerda is a little girl whose best friend, Kay, is taken by the Snow Queen after he is corrupted by pieces of a magic mirror that lodge in his eye and heart. There’s a lot of thinly veiled Christian symbolism here -- the creature who made the mirror is clearly the Devil -- but it’s enough for our character-based analysis to say merely that Kay is abducted to the Snow Queen’s palace. Gerda is devoted to Kay, and when he disappears, she takes the initiative to question all the witnesses of his disappearance. When they cannot provide satisfactory answers, she comes to the conclusion that he must have died.

Because literally everyone is rooting for Gerda, both the sun and the swallows assure her that Kay is not dead, and she decides to test this theory. She throws her most prized possession, a pair of red shoes, into the river in exchange for Kay’s presumably drowned body. When the river rejects her offering, she assumes that she just has to throw them further, and boards a boat to enable her to make this throw. Although she initially panics as she floats away, she eventually decides to sit back and enjoy the scenery while the river hopefully takes her to her lost friend. That’s how Gerda approaches most obstacles in the story: by accepting them as a necessary step in her journey to save Kay.

|

| Errol le Cain |

After interrogating the flowers and gaining nothing but confirmation of Kay’s continued existence, Gerda sets off, barefoot, to continue her quest. She comes upon a Raven, who tells her about another fascinating female character: a princess who is so clever that “she has read all the newspapers in the whole world, and has forgotten them again.” This princess decides to get married, but explicitly states that her prince will be someone intelligent and articulate, a man “who knew how to give an answer when he was spoken to--not one who looked only as if he were a great personage, for that is so tiresome.” She ends up choosing a suitor who had no intention of marrying her, but merely entered the castle in order to hear the princess’ wisdom. She chooses a husband who admires her brain, someone who, unlike the actual suitors, did not seek to win her but merely to hear her and enjoy her intellect.

Although Gerda sneaks into the princess’ castle -- her bare feet violate their strict “no shirt, no shoes, no royal assistance” policy -- the princess nevertheless allows her to stay the night and sends her on her way. Garbed in fine clothing and travelling in a carriage of pure gold, however, Gerda quickly gets robbed. The transition from the princess’ castle to the robbers’ woods marks the apparent shift from civilization to barbarism, from Disney-style aspirations to Grimm, violent reality.

Luckily, Gerda is ambushed by a group including one of the more interesting characters in fairy tales, the little robber girl. She is described, on various occasions, as wild, unmanageable, spoiled, and headstrong, and it probably comes as no surprise that she’s also pretty awesome. When the robber girl’s mother, a woman with “a long, scrubby beard, and bushy eyebrows that hung down over her eyes,” verbalizes her plan to eat Gerda, the robber girl bites her mother. The girl offers another plan: she will keep Gerda’s fine things, as well as Gerda herself. She also assures Gerda that she will not be killed, so long as she doesn’t anger the robber girl; in that case, the robber girl will kill her herself. The girl sleeps surrounded by dozens of animals, all kept and terrorized by her. Among them is a reindeer, whom she torments nightly with the long knife that she also sleeps with, because she lives in a world where “there is no knowing what may happen.”

Still, her harsh existence has in no way destroyed her ability to feel compassion. While she finds amusement in tormenting animals, it appears that the robber girl has been raised with the idea that violent actions can be used to express love and affection. She also possesses the ability to express these things in more traditional ways, as demonstrated when she comforts Gerda and when she sends her off to continue her journey, this time with the reindeer as both transportation and navigator.

|

| Milo Winter |

We return now to the rest of that journey. Before Gerda saves Kay, she receives help from two more women, one from Lapland and one from Finland. The Lapland woman offers sustenance, but can only refer Gerda to the Finland woman, to whom she writes a message on a dried fish. The Finland woman is an incredibly powerful figure, described by the reindeer thusly: "you can, I know, twist all the winds of the world together in a knot. If the seaman loosens one knot, then he has a good wind; if a second, then it blows pretty stiffly; if he undoes the third and fourth, then it rages so that the forests are upturned.” He requests that she give Gerda a potion to give her the strength of ten men, but she declines. This is not because she cannot brew such a potion, but because physical strength won’t help Gerda in the task ahead. She knows this because she, unlike everyone else in the story, appears to know exactly what has happened to Kay, down to the mirror shards embedded in his eye and heart. It is possible that she learns all of this from a parchment covered with strange figures. It’s almost as if she’s reading the story itself.

Even if she isn’t reading ahead, the Finland woman does have a kind of omniscience, as she figures out what has to happen next. She argues that she “can give [Gerda] no more power than what she has already. “Don't you see how great it is? Don't you see how men and animals are forced to serve her; how well she gets through the world barefooted? She must not hear of her power from us; that power lies in her heart, because she is a sweet and innocent child! If she cannot get to the Snow Queen by herself, and rid little Kay of the glass, we cannot help her.” Again, setting aside any symbolic implications for a narrative about good and evil, this is very cool. This is an incredibly powerful woman saying that she cannot empower a little girl any further, because the girl, in and of herself, has power enough on her own. She commands other living creatures, she receives intelligence from nature, and she does all of this without so much as a speck of foot protection. She’s something of an anti-Cinderella; instead of a set of ornamental shoes and a fairy godmother, she has her own feet and her own power.

Now, we must briefly address the symbolism. In order to infiltrate the Snow Queen’s castle, Gerda arms herself with the Lord’s Prayer. It summons a host of armoured angels to fight snowflakes and banish the cold from her limbs. The prayer also halts the winds that comprise the castle gate. Finally, it is a baptism of her “burning tears” that thaws Kay’s icy heart. Gerda’s power is, at the end, bolstered by the constancy of her faith and the innocence of youth.

|

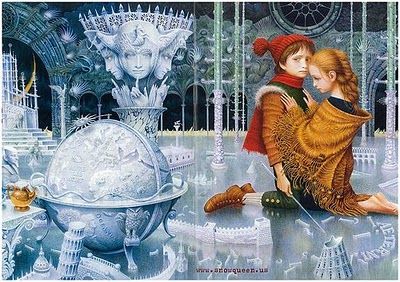

| Vadyslav Yerko |

Although this story is more than 165 years old, it seems bizarrely progressive in today’s media environment. While we’d like to commend Hans Christian Andersen for writing a tale that can still be considered forward-thinking today, we’d also like to take this opportunity to discuss why this progressiveness is, in itself, problematic. It all boils down to one question (which I, as is my wont, will stretch into two): If a 165-year-old story is still progressive, what does that say about the regressive nature of our contemporary storytelling? If it’s still progressive to write about a girl saving a boy, have we made any progress in dismantling the expectation that boys should save girls? Something can only be subversive if it is operating against an established norm; it can only be progressive if we are actually making progress.

This is one of the reasons we will be reviewing Disney’s Frozen. As a modern adaptation of “The Snow Queen,” the film could be expected to keep these same subversive qualities intact. From the information currently available, however, it appears as if Frozen will merely perpetuate the status quo. As far as we can tell, this film isn’t about the girl saving a boy, but about the girl falling for the boy; it’s not about women helping women, but about a new set of male sidekicks helping a woman in her quarrel with her sister. As we said in our preview, we hope that the film will prove us wrong. We would like nothing more than for Frozen to prove itself truly progressive, to ditch the same old freezer burnt tropes and use this opportunity to improve on a classic. Unfortunately, having seen no mention of the little robber girl or many of the other women in the story, we’re not holding out much hope.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

Monday, 28 January 2013

Miscellaneous Mondays: Female Monsters

This

week’s Miscellaneous Monday is brought to you by the brilliance of

Tumblr user terror-incognita, who summed up a tremendous problem in media (and one of my pet issues) in a single paragraph:

I once had a lengthy argument about just this issue. My male conversation partner argued in favour of our current standard of female villainy, suggesting that women must enact their evil through their seductive appeal. What makes these women terrifying is the control they exert over men using the innate power of their sexuality. The example he gave was Angelina Jolie as Grendel’s mother in Beowulf (2007). I suggested that such an approach was reductive nonsense.

I, like terror-incognita, am sick of seeing monstrous women as pretty, humanoid corpses or gorgeous succubi. Hollywood dictates that female monsters must be attractive, causing pleasure while wreaking destruction. We rarely get the opportunity to see truly monstrous women, because it seems that being sexy is more important than being terrifying. What I’d like to see is more female Grendels, mutilating and consuming dozens of people at a time before having their arms ripped off in a violent struggle. I’d also like to see these kinds of monsters embrace their rage without this rage being reduced to some supernatural example of that time-tested adage that “bitches be crazy.”

What really strikes me in terror-incognita’s observations, however, are those final lines: “I want to see how you get strong without being broken first. Get strong and stay strong. Get big and bigger.” We started this blog with a post that riffed on Joss Whedon’s responses to the question of why he writes strong female characters. Although we wanted to use the form of his speech, we also wanted to begin by acknowledging a writer whose work with female characters is contentious. In many cases, his writing is contentious for just this reason: many of Whedon’s women must be broken before they can become strong.

A basic Internet search should produce a number of critical analyses of this trope in Whedon’s work. I’m not interested in getting into the details of these issues in this post -- though rest assured, we will be doing a whole host of Whedonverse series -- but I will offer two examples. In Firefly and its accompanying materials, we learn that River Tam underwent extensive, traumatic experimentation in order to become the perfect assassin. In Dollhouse, Echo had her self removed in order to have it replaced by a whole host of plug and play personalities before she ultimately fashioned a complete self.

As another tumblr user, sorveharth, observes, “I think the main difference between a hero and a heroine in traditional narratives is that a hero’s strength is defined by how much he can win, while a heroine’s is defined by how much loss she can endure.” I don’t know about you, but I agree with sorveharth in saying that “that’s kinda fucked up.”

For further discussion of the problematic implications of women being broken in order to become strong, see also: Rape As Backstory and Sorry, But Rape Won’t Make Your Female Character More Interesting.

I

want to see more girl monsters. Girl giants, girl dragons, hulks &

trolls. Scylla and hydra. Girl monsters who are huge and whole. Teeth

and plush fur and long muscled tails. Heads enough to see you anywhere.

Gleaming green or brown. But girl monsters are usually zombies or

vampires. Pale and thin, bleeding or dead. Not Lady Lazarus, not a

phoenix from the ash. I want to see how you get strong without being

broken first. Get strong and stay strong. Get big and bigger.

I once had a lengthy argument about just this issue. My male conversation partner argued in favour of our current standard of female villainy, suggesting that women must enact their evil through their seductive appeal. What makes these women terrifying is the control they exert over men using the innate power of their sexuality. The example he gave was Angelina Jolie as Grendel’s mother in Beowulf (2007). I suggested that such an approach was reductive nonsense.

I, like terror-incognita, am sick of seeing monstrous women as pretty, humanoid corpses or gorgeous succubi. Hollywood dictates that female monsters must be attractive, causing pleasure while wreaking destruction. We rarely get the opportunity to see truly monstrous women, because it seems that being sexy is more important than being terrifying. What I’d like to see is more female Grendels, mutilating and consuming dozens of people at a time before having their arms ripped off in a violent struggle. I’d also like to see these kinds of monsters embrace their rage without this rage being reduced to some supernatural example of that time-tested adage that “bitches be crazy.”

What really strikes me in terror-incognita’s observations, however, are those final lines: “I want to see how you get strong without being broken first. Get strong and stay strong. Get big and bigger.” We started this blog with a post that riffed on Joss Whedon’s responses to the question of why he writes strong female characters. Although we wanted to use the form of his speech, we also wanted to begin by acknowledging a writer whose work with female characters is contentious. In many cases, his writing is contentious for just this reason: many of Whedon’s women must be broken before they can become strong.

A basic Internet search should produce a number of critical analyses of this trope in Whedon’s work. I’m not interested in getting into the details of these issues in this post -- though rest assured, we will be doing a whole host of Whedonverse series -- but I will offer two examples. In Firefly and its accompanying materials, we learn that River Tam underwent extensive, traumatic experimentation in order to become the perfect assassin. In Dollhouse, Echo had her self removed in order to have it replaced by a whole host of plug and play personalities before she ultimately fashioned a complete self.

As another tumblr user, sorveharth, observes, “I think the main difference between a hero and a heroine in traditional narratives is that a hero’s strength is defined by how much he can win, while a heroine’s is defined by how much loss she can endure.” I don’t know about you, but I agree with sorveharth in saying that “that’s kinda fucked up.”

For further discussion of the problematic implications of women being broken in order to become strong, see also: Rape As Backstory and Sorry, But Rape Won’t Make Your Female Character More Interesting.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)