“To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. All emotions, and that one particularly, were abhorrent to his cold, precise, but admirably balanced mind. … And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.”

- John Watson (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) in “A Scandal in Bohemia”

This season, CBS premiered Elementary, a new crime procedural based on the oft-adapted Sherlock Holmes canon. In the show’s pilot, Joan Watson deduces that a woman was behind Sherlock’s relocation from London to New York. In its sixth episode, she learns that the woman in question is named Irene. For viewers with even a passing familiarity with Sherlock Holmes, Irene Adler’s inclusion in the show was a foregone conclusion the moment a woman entered the equation. Who could it be but the woman?

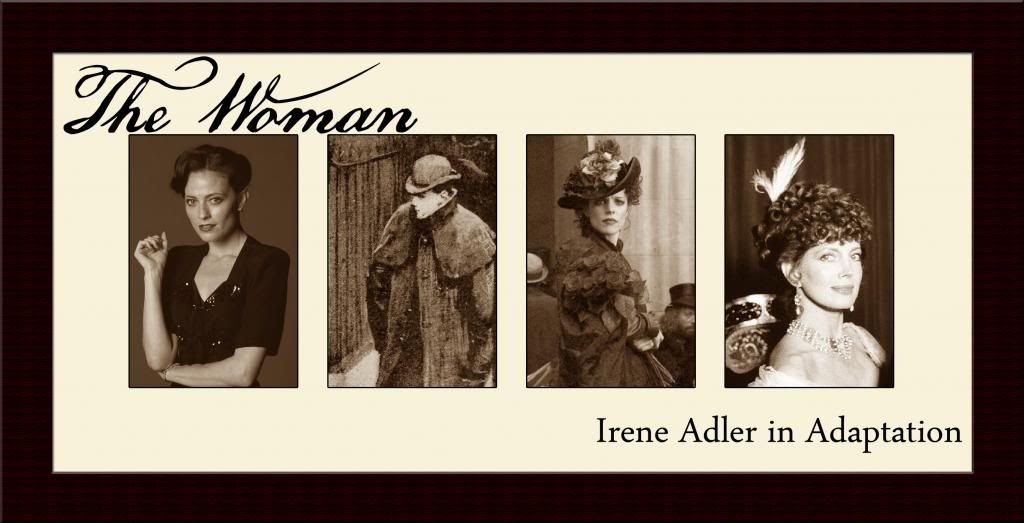

This week we start a three-part examination of Irene Adler, comparing her characterization in the original story with three different adaptations: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, produced by Granada Television, Sherlock Holmes, directed by Guy Ritchie, and Sherlock, produced by the BBC.

Original Story

In

the original story, Irene Adler finds herself at the centre of a

scandal which, if made public, could have repercussions on a global

scale. Or so says the King of Bohemia, a man dumb enough to allow

photographic evidence of an affair more than a hundred years before he

could blame it on Photoshop. Some time after the relationship has ended,

Irene threatens to send the incriminating picture to the family of his

virtuous fiancée on the day the engagement is publicly announced,

intending to humiliate the king and end his marriage before it can even

take place.

In

the original story, Irene Adler finds herself at the centre of a

scandal which, if made public, could have repercussions on a global

scale. Or so says the King of Bohemia, a man dumb enough to allow

photographic evidence of an affair more than a hundred years before he

could blame it on Photoshop. Some time after the relationship has ended,

Irene threatens to send the incriminating picture to the family of his

virtuous fiancée on the day the engagement is publicly announced,

intending to humiliate the king and end his marriage before it can even

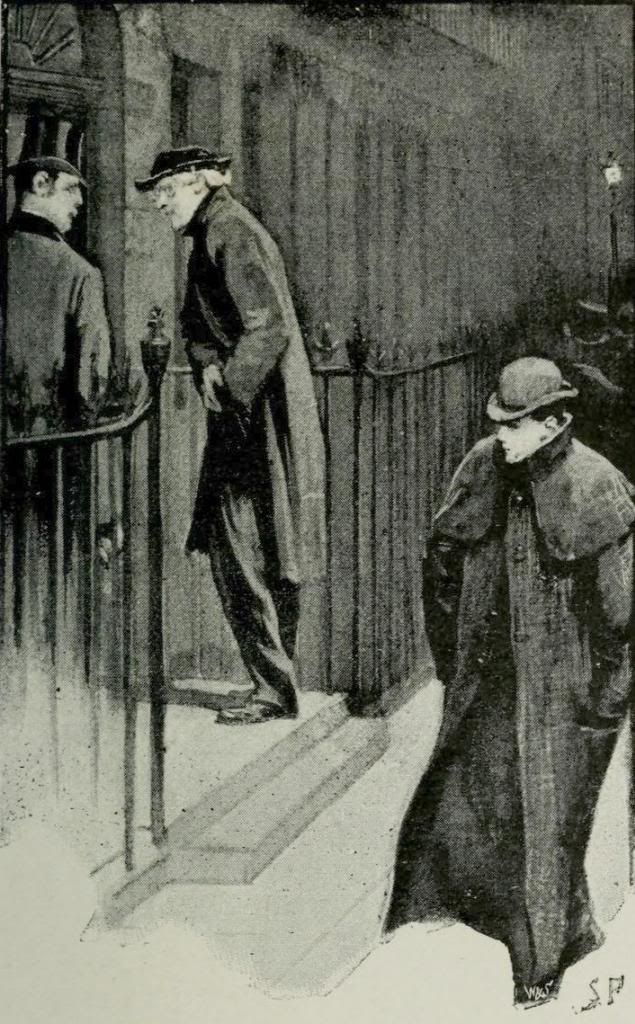

take place.This is where Sherlock Holmes enters the story; five attempts to find the photo have been unsuccessful, and he is the king’s last hope against a more than formidable opponent. As we learn, Irene is an adventuress and retired opera singer with “a soul of steel ... the face of the most beautiful of women, and the mind of the most resolute of men.” Her word is inviolate. She is beautiful, kind, and graceful, and the king suggests that she would have made an excellent queen. At the same time, she is apparently entirely convincing as a young man when she walks on the street, at those times when she wants to enjoy the freedom that being a woman denies her.

We know all of this primarily because the men in the story spend most of it talking about how awesome she is. This praise is completely deserved, as we learn when she beats the great Sherlock Holmes. Although she doesn’t initially see through his disguises, she does come to realize that he’s tricked her into revealing the location of the photograph. To confirm her suspicions, she follows him to his home, assuming a disguise herself and turning his own methods against him. She denies him the satisfaction of finding the original picture by taking flight, promising not to use it as anything but insurance against the king’s vengeance. Finally, she seems to disprove the king’s claim that she is motivated by jealousy, as she loves and is loved by “a better man than he.”

To us, this is one of the most intriguing aspects of Irene Adler; her life doesn’t revolve around a man. The king assumes that she is motivated by jealousy, but she actually seems more set on revenge for the wrongs he did her. She does marry Godfrey Norton, but that relationship seems to work according to her terms. Sherlock Holmes comes to know her as “the woman,” but she quite clearly does not think of him as “the man.” He is, instead, referred to as a formidable antagonist. Afterwards, she doesn’t appear to be as profoundly affected by the situation as Sherlock; she would be unlikely to keep his portrait.

As Watson suggests, the case details “how the best plans of Mr. Sherlock Holmes were beaten by a woman’s wit. He used to make merry over the cleverness of women, but I have not heard him do it of late. And when he speaks of Irene Adler, or when he refers to her photograph, it is always under the honourable title of the woman.”

While we’re always happy to see a story end with a misogynist seeing the error of his ways (see also: Grumpy’s character arc, the one positive development in Snow White), this moniker strikes us as an interesting problem. Sherlock Holmes’ newfound respect for women is focused on one particular individual, who apparently towers above the rest. In addition, this singular female has “the mind of the most resolute of men” and makes a habit of passing for a man. There’s an unpleasant implication in the fact that the woman who both exemplifies and overshadows womanhood seems to be able to do so because of her ostensibly masculine traits. To be the woman, you have to be man enough for the job.

Still, the fact remains that Irene Adler beats Sherlock Holmes at his own game and then basically rides off into the sunset to continue living her life. Regardless of her canonical label, we think of her as a strong female character.

Granada Holmes

To our minds, the best adaptation of this story is the one that aired as the first episode of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in 1984. Second place goes to the Wishbone version, demoted only because we’re not sure what lesson we’re supposed to learn from a woman outsmarting a dog.

This adaptation is almost disturbingly accurate, with much of the dialogue taken straight from the original text. There are, however, two notable changes. The first is that the episode has the King of Bohemia explicitly state that Irene’s vindictiveness stems from his refusal to marry her. The original story never gives the exact nature of the king’s betrayal, and “didn’t put a ring on it” is literally the least compelling explanation for this level of vengeance. We’re not saying it’s wrong, but we are saying it’s only one of any number of things one person in a relationship could do to hurt another.

The other alteration is the addition of a discussion between Irene Adler and Sherlock Holmes -- the latter in the guise of a clergyman -- about the nature of revenge. Holmes observes that “there are people in this world … to whom revenge is, in itself, a reward.” Irene responds that she can’t imagine such feelings. She can, however, imagine that some random guy turning up and implying that she should lay off the revenge seems a little fishy. This is a particularly interesting scene because it depicts the moment when Irene realizes that she’s been tricked, a moment that Watson’s narration prevents us from reading firsthand in the original. This is the moment when the tables turn. It is also the moment when Holmes encourages Irene to relinquish her need for revenge, giving him a weird, indirect role in his own defeat.

The last we see of Irene Adler, she is tossing the incriminating photo overboard and making out with her new husband. While Sherlock Holmes looks at her picture and pensively plays his violin, she moves on.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

No comments:

Post a Comment