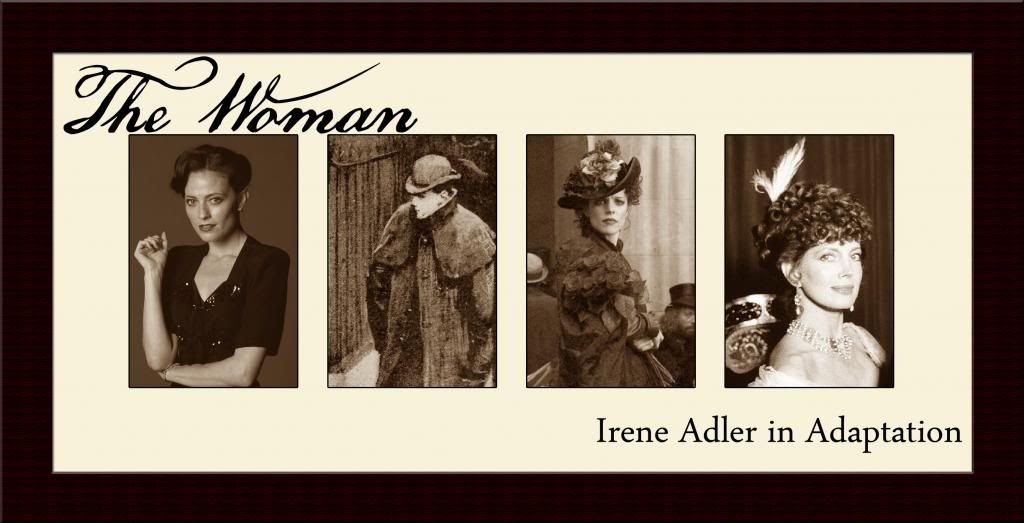

The blurb on the back of copies of Guy Ritchie’s 2009 adaptation, Sherlock Holmes, calls the film “a bold reimagining that makes the famed sleuth a daring man of action as well as a peerless man of intellect.” On the same cover we see images of Irene Adler, a woman who proved herself to be, at the very least, Holmes’ intellectual peer. The film sees no problem with this, and therein lies our problem with it.

The

Irene Adler that appears opposite Robert Downey Jr.’s Sherlock Holmes

is not the one that graces the pages of Conan Doyle’s story. Whereas the

original Irene was an opera singer and adventuress, this one is a

“world-class thief.” She doesn’t get mixed up in scandal because she

happened to date the wrong royal, but because she makes a habit of

robbing royals blind. In fact, in addition to the crimes she commits

against the governments and monarchs of India, Bulgaria, and Spain, she

was involved in a scandalous affair that ended a royal engagement.

That’s right: Ritchie’s Irene apparently carried out her threat against

the King of Bohemia. This last point seems to suggest that the film is

less an adaptation than a continuation set in an alternate universe.

The

Irene Adler that appears opposite Robert Downey Jr.’s Sherlock Holmes

is not the one that graces the pages of Conan Doyle’s story. Whereas the

original Irene was an opera singer and adventuress, this one is a

“world-class thief.” She doesn’t get mixed up in scandal because she

happened to date the wrong royal, but because she makes a habit of

robbing royals blind. In fact, in addition to the crimes she commits

against the governments and monarchs of India, Bulgaria, and Spain, she

was involved in a scandalous affair that ended a royal engagement.

That’s right: Ritchie’s Irene apparently carried out her threat against

the King of Bohemia. This last point seems to suggest that the film is

less an adaptation than a continuation set in an alternate universe.Still, such a version would require that Irene remain fundamentally herself. We don’t think that that’s the case here. As we see it, the difference lies in the fact that the textual Irene possesses the photograph, while the filmic Irene embodies it. The original has some power over her own representation, while the adaptation is merely the picture as Holmes sees it. What makes this even more problematic is that this Holmes sees not through a magnifying glass, but through a camera. She is no longer the woman, but a femme fatale.

In this film, Irene Adler is identified with objects on several occasions. She is introduced through a monogrammed handkerchief that she leaves to get Holmes’ attention during a boxing match. Only after he recognizes it does he look for the woman who left it. When she arrives at Holmes’ apartment to offer him a case, her effect on him is demonstrated through the hiding and revealing of her portrait. Not long after she arrives, he leaps to lay the picture face down, trying to keep her from realizing that he has had it on display as a treasured memento. On her way out, she flips it back up, letting him know that she sees right through him. The most troubling identification occurs when Irene is hung up like a pig carcass: a fairly literal piece of meat.

These examples bring us to one of our major issues with this adaptation: the romantic relationship between Sherlock Holmes and Irene Adler. If you’ve been reading the blog upto this point, you may have noticed that a number of our posts isolate the moment when boy meets girl as the point when everything falls apart. This isn’t because we hate romantic plots or sub-plots (we don’t), but because female characters tend to get caught up in the male lead’s gravitational pull and spend the rest of the movie caught in his orbit. This leaves us with planets, not stars.

We

don’t really want to belabour the metaphor any further, so suffice it

to say that the same thing happens here. We learn that Sherlock and

Irene have intimate knowledge of each other; she knows his favourite

foods, he knows her criminal signature. He also knows which room they

frequented at the Grand, because obviously a man and a woman could never

have a platonic relationship based on mutual respect for their

intellect and cunning. This intimacy also leads to a very different take

on “the woman.”

This Holmes does not use the iconic title as a sign of respect;

instead, he uses her name most of the time and saves the title for those

situations when he’s angry or frustrated with her. On these occasions

it is never “the woman,” but “Woman!” -- almost as if Sherlock Holmes has temporarily been replaced by Glee’s Artie Abrams.

We

don’t really want to belabour the metaphor any further, so suffice it

to say that the same thing happens here. We learn that Sherlock and

Irene have intimate knowledge of each other; she knows his favourite

foods, he knows her criminal signature. He also knows which room they

frequented at the Grand, because obviously a man and a woman could never

have a platonic relationship based on mutual respect for their

intellect and cunning. This intimacy also leads to a very different take

on “the woman.”

This Holmes does not use the iconic title as a sign of respect;

instead, he uses her name most of the time and saves the title for those

situations when he’s angry or frustrated with her. On these occasions

it is never “the woman,” but “Woman!” -- almost as if Sherlock Holmes has temporarily been replaced by Glee’s Artie Abrams.After she leaves 221B Baker Street, Irene has a rendezvous with her employer, who informs her that her connection to Sherlock is the only reason why he hired her. She can manipulate the great detective, and her employer can control her because, as it turns out, her weakness is her love for Sherlock.

Our biggest problem with this version of Irene Adler is that she’s controlled by men. When Holmes meets her at the hotel, he tells her that she’s in over her head and informs her that he will be taking her to either the railway station or the police station, regardless of her thoughts on the matter. Given his paternalistic attitude, it’s not surprising that she decides to drug him. Of course, he does end up handcuffing her to a construction site. The villain of this film, Lord Blackwood, chains a bound and gagged Irene to a hook that draws her ever closer to a saw used to cut pigs in half. His disembodied voice tells Sherlock, “She followed you here, Holmes. You led your lamb to slaughter.” He dehumanizes and dismisses Irene, all while making Sherlock responsible for actions she herself chose to take. The shadowy figure, who turns out to be (to absolutely no one’s surprise) Professor Moriarty, manipulates her at every turn. Even when Irene tries to quit, he tells her that he will be the one to tell her when she can leave his employ. He takes her agency and, in the second movie, it is implied that he takes her life.

Still, there’s something about this Irene Adler that we appreciate: she is a perfect example of our name, the very definition of what we call the Strong Female Character™. When its audience calls for the portrayal of strong women onscreen, Hollywood tends to respond with a kind of character whose strength is superficial at best and nonexistent at worst. Viewers demand depictions of living, breathing people with all their accompanying strengths and flaws, and Hollywood provides very lifelike cardboard cutouts. Ritchie’s version of Irene Adler embodies this problem. She has tremendous sexual confidence but, as with many of these characters, this trait seems to exist merely to justify the existence of a scene that begins with her wearing a sheet and goes on to show her undressing. Her sexual confidence is less for her than for the presumed male viewer. Her apparently remarkable intelligence fluctuates wildly, as she easily tricks the great Sherlock Holmes in one scene only to waste bullets shooting at people in a room containing a chemical weapon in another. She wears masculine dress in a suitably feminine way. The real clincher, though, is the scene in which she is being threatened by two men in an alley. With the implicit threat of sexual assault looming, Irene fights the men off in a scuffle that ends with her knifepoint lodged against the throat of one of her assailants. Observing unseen, Sherlock says, “That’s the Irene I knew.”

We’re glad he recognizes her, because we certainly don’t.

Verdict: Strong Female Character™

No comments:

Post a Comment