|

| Honor C. Appleton |

The subject of this first post is markedly different than the vast majority of the tales that have come to form the backbone of Western popular culture. Published in 1845, “The Snow Queen” by Hans Christian Andersen stands out from both the crowd of male-centric stories we tell today and the throng of cautionary tales starring girls and women that come to us from The Brothers Grimm. “The Snow Queen” is a story that revolves around and celebrates women, as evidenced by the fact that, of the seven sections, six are named in whole or in part after women. We are all familiar with tales in which the male hero saves the damsel in distress, and most of us are probably well-versed in the modern subversions of these stories, in which the dude in distress is saved by a heroine. What “The Snow Queen” offers us is a take on the latter before it was cool. (Consider yourself warned; that was not the last ice joke.)

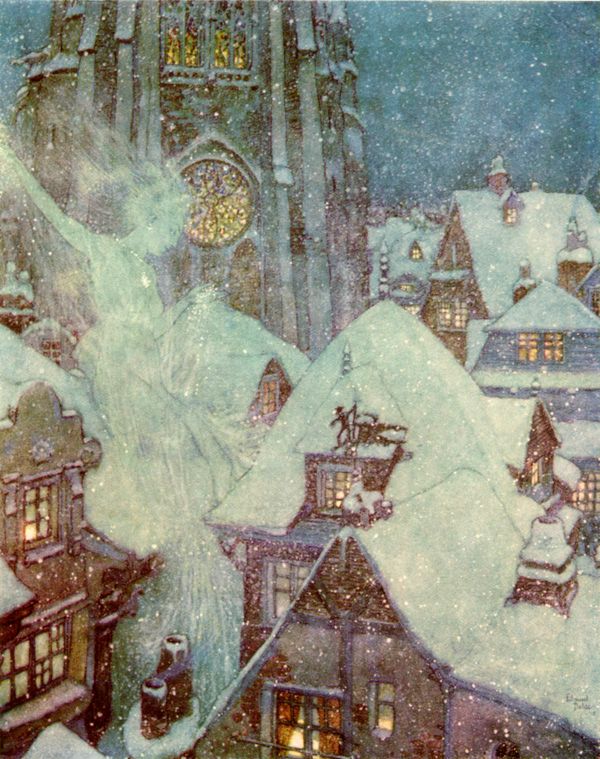

|

| Edmund Dulac |

This is further demonstrated in her treatment of Kay. In order to take Kay further into her realm, she kisses him twice; the first kiss stops him from feeling the cold, while the second makes him forget Gerda and the rest of his loved ones. She states, “Now you will have no more kisses... or else I should kiss you to death!” The only affection her lips can provide is frostbite, and the expression of what others might term warmth results in her victims freezing to death.

Before she becomes a hero, Gerda is a little girl whose best friend, Kay, is taken by the Snow Queen after he is corrupted by pieces of a magic mirror that lodge in his eye and heart. There’s a lot of thinly veiled Christian symbolism here -- the creature who made the mirror is clearly the Devil -- but it’s enough for our character-based analysis to say merely that Kay is abducted to the Snow Queen’s palace. Gerda is devoted to Kay, and when he disappears, she takes the initiative to question all the witnesses of his disappearance. When they cannot provide satisfactory answers, she comes to the conclusion that he must have died.

Because literally everyone is rooting for Gerda, both the sun and the swallows assure her that Kay is not dead, and she decides to test this theory. She throws her most prized possession, a pair of red shoes, into the river in exchange for Kay’s presumably drowned body. When the river rejects her offering, she assumes that she just has to throw them further, and boards a boat to enable her to make this throw. Although she initially panics as she floats away, she eventually decides to sit back and enjoy the scenery while the river hopefully takes her to her lost friend. That’s how Gerda approaches most obstacles in the story: by accepting them as a necessary step in her journey to save Kay.

|

| Errol le Cain |

After interrogating the flowers and gaining nothing but confirmation of Kay’s continued existence, Gerda sets off, barefoot, to continue her quest. She comes upon a Raven, who tells her about another fascinating female character: a princess who is so clever that “she has read all the newspapers in the whole world, and has forgotten them again.” This princess decides to get married, but explicitly states that her prince will be someone intelligent and articulate, a man “who knew how to give an answer when he was spoken to--not one who looked only as if he were a great personage, for that is so tiresome.” She ends up choosing a suitor who had no intention of marrying her, but merely entered the castle in order to hear the princess’ wisdom. She chooses a husband who admires her brain, someone who, unlike the actual suitors, did not seek to win her but merely to hear her and enjoy her intellect.

Although Gerda sneaks into the princess’ castle -- her bare feet violate their strict “no shirt, no shoes, no royal assistance” policy -- the princess nevertheless allows her to stay the night and sends her on her way. Garbed in fine clothing and travelling in a carriage of pure gold, however, Gerda quickly gets robbed. The transition from the princess’ castle to the robbers’ woods marks the apparent shift from civilization to barbarism, from Disney-style aspirations to Grimm, violent reality.

Luckily, Gerda is ambushed by a group including one of the more interesting characters in fairy tales, the little robber girl. She is described, on various occasions, as wild, unmanageable, spoiled, and headstrong, and it probably comes as no surprise that she’s also pretty awesome. When the robber girl’s mother, a woman with “a long, scrubby beard, and bushy eyebrows that hung down over her eyes,” verbalizes her plan to eat Gerda, the robber girl bites her mother. The girl offers another plan: she will keep Gerda’s fine things, as well as Gerda herself. She also assures Gerda that she will not be killed, so long as she doesn’t anger the robber girl; in that case, the robber girl will kill her herself. The girl sleeps surrounded by dozens of animals, all kept and terrorized by her. Among them is a reindeer, whom she torments nightly with the long knife that she also sleeps with, because she lives in a world where “there is no knowing what may happen.”

Still, her harsh existence has in no way destroyed her ability to feel compassion. While she finds amusement in tormenting animals, it appears that the robber girl has been raised with the idea that violent actions can be used to express love and affection. She also possesses the ability to express these things in more traditional ways, as demonstrated when she comforts Gerda and when she sends her off to continue her journey, this time with the reindeer as both transportation and navigator.

|

| Milo Winter |

We return now to the rest of that journey. Before Gerda saves Kay, she receives help from two more women, one from Lapland and one from Finland. The Lapland woman offers sustenance, but can only refer Gerda to the Finland woman, to whom she writes a message on a dried fish. The Finland woman is an incredibly powerful figure, described by the reindeer thusly: "you can, I know, twist all the winds of the world together in a knot. If the seaman loosens one knot, then he has a good wind; if a second, then it blows pretty stiffly; if he undoes the third and fourth, then it rages so that the forests are upturned.” He requests that she give Gerda a potion to give her the strength of ten men, but she declines. This is not because she cannot brew such a potion, but because physical strength won’t help Gerda in the task ahead. She knows this because she, unlike everyone else in the story, appears to know exactly what has happened to Kay, down to the mirror shards embedded in his eye and heart. It is possible that she learns all of this from a parchment covered with strange figures. It’s almost as if she’s reading the story itself.

Even if she isn’t reading ahead, the Finland woman does have a kind of omniscience, as she figures out what has to happen next. She argues that she “can give [Gerda] no more power than what she has already. “Don't you see how great it is? Don't you see how men and animals are forced to serve her; how well she gets through the world barefooted? She must not hear of her power from us; that power lies in her heart, because she is a sweet and innocent child! If she cannot get to the Snow Queen by herself, and rid little Kay of the glass, we cannot help her.” Again, setting aside any symbolic implications for a narrative about good and evil, this is very cool. This is an incredibly powerful woman saying that she cannot empower a little girl any further, because the girl, in and of herself, has power enough on her own. She commands other living creatures, she receives intelligence from nature, and she does all of this without so much as a speck of foot protection. She’s something of an anti-Cinderella; instead of a set of ornamental shoes and a fairy godmother, she has her own feet and her own power.

Now, we must briefly address the symbolism. In order to infiltrate the Snow Queen’s castle, Gerda arms herself with the Lord’s Prayer. It summons a host of armoured angels to fight snowflakes and banish the cold from her limbs. The prayer also halts the winds that comprise the castle gate. Finally, it is a baptism of her “burning tears” that thaws Kay’s icy heart. Gerda’s power is, at the end, bolstered by the constancy of her faith and the innocence of youth.

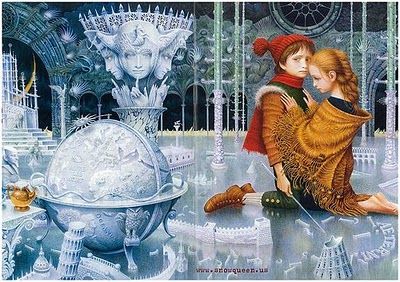

|

| Vadyslav Yerko |

Although this story is more than 165 years old, it seems bizarrely progressive in today’s media environment. While we’d like to commend Hans Christian Andersen for writing a tale that can still be considered forward-thinking today, we’d also like to take this opportunity to discuss why this progressiveness is, in itself, problematic. It all boils down to one question (which I, as is my wont, will stretch into two): If a 165-year-old story is still progressive, what does that say about the regressive nature of our contemporary storytelling? If it’s still progressive to write about a girl saving a boy, have we made any progress in dismantling the expectation that boys should save girls? Something can only be subversive if it is operating against an established norm; it can only be progressive if we are actually making progress.

This is one of the reasons we will be reviewing Disney’s Frozen. As a modern adaptation of “The Snow Queen,” the film could be expected to keep these same subversive qualities intact. From the information currently available, however, it appears as if Frozen will merely perpetuate the status quo. As far as we can tell, this film isn’t about the girl saving a boy, but about the girl falling for the boy; it’s not about women helping women, but about a new set of male sidekicks helping a woman in her quarrel with her sister. As we said in our preview, we hope that the film will prove us wrong. We would like nothing more than for Frozen to prove itself truly progressive, to ditch the same old freezer burnt tropes and use this opportunity to improve on a classic. Unfortunately, having seen no mention of the little robber girl or many of the other women in the story, we’re not holding out much hope.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

I love your blog! I just stumbled on this in doing some research on THE SNOW QUEEN, as it's my favorite fairy tale, and I'm so absolutely crushed over what Disney is doing to it. This was an awesome essay!

ReplyDeleteThanks! I love writing the blog, so I'm glad you enjoy reading it.

DeleteI actually read "The Snow Queen" for the first time to discuss it here, and now I adore it. While I'm looking forward to eviscerating the Disney version, should it prove to be as problematic as the promo material suggests, I would prefer a proper adaptation that left me with little to say. It's a story that deserves the Disney treatment, but at the same time, it's too good for the Disney treatment, you know?

Im doing the snow queen for my play this year��

DeleteWow! I feel so grateful that I came across this page just after reading The Snow Queen. I initially read it just for the story but this gave me so much more insight and understanding as to what else lies beneath the simple storyline. I could never have thought by myself how the presence of even the most minor characters could make all of it so much more powerful and meaningful.

ReplyDeleteThis is the first of your articles that I've read, and I look forward to browsing for more, haha! Wonderful post!!

I just stumbled across this post whilst doing research for my Snow Queen illustration project and now I have to read the rest of your posts!

ReplyDeleteThank you for opening my eyes to the various underlying themes to this story! :)

http://selinaquachfmp.blogspot.co.uk/

I actually read the Snow Queen after seeing (and loving) Frozen because so many of my friends were telling me how much it ruined the story. In a sense they’re right: Frozen has a reindeer, a queen who can make snow, and a frozen heart, and there the similarities end. I understand how frustrating it can be when a movie completely destroys the original story, but let’s just remember that Disney doesn’t claim to be doing the original story justice at all. Frozen is inspired by rather than based on the Snow Queen, and there’s a further similarity that needs to be recognized. Anderson was careful to tell us that the love between Kai and Gerda was like that between a brother and sister, and what does Disney give us in Frozen? None of my friends can quite agree on exactly who saves whom in Frozen, but everyone agrees that the movie isn’t about Anna and Hans or even Anna and Kristoff; it’s about Anna and Elsa, who save each other through sisterly love. So even if Disney completely through all the other strong female characters out the window and decided to make fun of itself by having a Disney Princess say, “You can’t marry a man you just met”, is Anderson’s theme really lost at all?

ReplyDeleteBoth the clever princess and the robber girl are pretty strong females as well. The princess in this story is my favourite fairytale character, for I identify with her:

ReplyDelete"another fascinating female character: a princess who is so clever that “she has read all the newspapers in the whole world, and has forgotten them again.” This princess decides to get married, but explicitly states that her prince will be someone intelligent and articulate, a man “who knew how to give an answer when he was spoken to--not one who looked only as if he were a great personage, for that is so tiresome.” She ends up choosing a suitor who had no intention of marrying her, but merely entered the castle in order to hear the princess’ wisdom. She chooses a husband who admires her brain, someone who, unlike the actual suitors, did not seek to win her but merely to hear her and enjoy her intellect."

Impressive!

What's wrong with Gerda acting out of romantic love? Does it really make a difference? Does that somehow cast a shadow over the deeds she accomplishes? I'm not saying I buy that their love is romantic, but why should it matter?

ReplyDeleteThe motif of the woman saving her prince is present in many stories. In most the girl causes a curse to become permanent and as a result must search the world for her lost prince. Now a few things that i think you did not speak enough of is that most characters have a selfish possessive love and Gerda teaches them how true love is.

ReplyDeleteNightcrawler, good point! I hadn't thought of it, but you are correct: Gerda roaming the world in search of cursed Kai does share similarities with the ancient Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche. I seem to also vaguely recall a couple Grimm or other fairy tales that shared the theme. While Cupid and Psyche represent heart and mind, H. C. Andersen flips the sexes for Kai (male, emotionless mind) and Gerda (female, loving heart). It does seem that he intentionally retold/heavily borrowed from the Cupid and Psyche myth, as did the French _Beauty and the Beast_.

DeleteYet Gerda is different in that she is innocent. Psyche was required to wear through three pairs of iron sandals before being allowed to reunite with her husband Cupid, to atone for her Pandora-like, Eve-like sin of doing the forbidden out of curiosity. Yes, you are right, the robber girl and the spring witch desire Gerda in a selfish, possessive way, but Gerda is willing to sacrifice and struggle to help Kai with a selfless love.

Most fairy and folk tales I inhaled as a child featured male heroes, sidekicks, villains, testers, challengers, and so on, with a princess offered merely as a symbolic reward for completing a quest. The male quests usually weren't about love, only winning the princess as a trophy. Nevertheless, I was moved by the many that emphasized generous, selfless sharing, and helping of characters along the way, which was rewarded with later help completing the quest. The moral clearly echoed The Golden Rule and the parable of The Good Samaritan. ////Bunny kisses for all!

However, Nightcrawler, I can't remember the other tales well enough, but in "Cupid and Psyche", Psyche doesn't "save" Cupid in the version I read. He's fine; she's just not allowed to be with him until she atones for viewing him while he slept, which he(?) forbade as a test of fidelity/obedience, I think, like the tree of knowledge's fruit in Eden. Cupid slept in his beautiful human form rather than his monstrous daytime disguise (emulated by _Beauty and the Beast_). I think the other tales are similar.

DeleteI can't remember any tales wherein a heroine saves her man, besides "The Snow Queen," in which Gerda saves Kai via platonic love, and Mme. Beaumont's _Beauty and the Beast_, in which Belle saves first her father, through filial self-sacrifice, then the Beast, through love and forgiveness. Other than those two, the closest example I can think of is Andersen's "The Wild Swans"; Elisa saves her (younger, I think?) *brothers* through self-sacrifice and loyalty.

Well, the Little Mermaid saves the drowning prince when he's unconscious, so there's no threat of him seeming "weak" for needing female help. And the princess of "The Sea Maiden" (and a similar tale) tempts the mermaid into surfacing with her kidnapped hero, but she is immediately taken in his place, and he must do the intricate, main rescue of her. These rescues are brief, minor episodes in their tales.

Many heroines save *themselves* through cleverness, perseverance through hardship, etc.: for example, the heroines of "Rumplestiltskin," "Allerleirauh/Thousandfurs," "The Peasant's Wise Daughter," and "Cap O'Rushes."

Can anyone here, including you, Nightcrawler, name any specific folk/fairy tales with the "motif of the woman saving her prince"? I hope they do exist; I'm eager to read them, or to be reminded of them, if I did read some long ago. I would especially love to see a heroine rescue a man using intelligence, cleverness, bravery, badassery, strength/fortitude, or another so-called "masculine" trait. ////Bunny kisses for all!

P.S. Is there a way to edit comments? I would like to change "...retold/heavily borrowed from..." to "...partly retold/borrowed from..." in my above comment, and add the parenthetical phrase here: "the robber girl (at first) and the spring witch..."

[Part 1] Megan Croutch, an odd thought just occurred to me. Why, I wondered, does H. C. Andersen have so many female protagonists ("The Little Mermaid," "The Little Match Girl," Gerda, Elisa of "The Wild Swans," Thumbelina, "The Bog King's Daughter,"…)? Is it really because he's so progressive? His tales, like those of C. S. Lewis, promote Christian ideals.

ReplyDeleteCould it be that Andersen, rather than being nonsexist, actually believed that females were *inherently better* at lovingkindness, humility, self-sacrifice? During the suffragist era, some people made the argument that women should be able to vote, not to achieve justice, but *because* they would have a gentling influence, due to their supposed genetic tendencies toward compassion and selflessness and away from violence and conflict.

Andersen does have deeply loving (in the agape sense) and self-sacrificing male characters like [cross out: "The Happy Prince" and his volunteer swallow emissary, and] "The Steadfast Tin Soldier" (romantic, not agape love, though), so I'm unsure about this new hypothesis of mine. I'll need to look at Andersen's oeuvre. [Oops, I conflated Oscar Wilde's _The Happy Prince and Other Tales_ with Andersen's work. But the statue's lead heart and the sparrow are thrown in the trash at the end, just like the soldier's heart and ballerina's spangle. Somebody is copying somebody; perhaps both are copying earlier tales.]

It seems very much of his sexist times that Thumbelina's only apparent purpose is to be married off, and she's supposed to be happy with the first little man she sees. And I found it disturbing that in "The Traveling Companion," the enchanted, "evil" princess needs to be beaten and dunked into submission by a man. I did just read "The Wyvern King," though, in which the princess flays the enchanted prince to save him, so now I don't think that detail is sexist or misogynistic. It's important to have a large sample to draw accurate conclusions about patterns! [cont. in Part 2]

[Part 2] In that vein, looking at one data point, “The Snow Queen,” and saying that we have not progressed because this story still seems progressive, is called cherry-picking data (datum, in this case!). We do have much further to go for true equal representation, but if you look at the *overall* picture, surely there are many more strong female protagonists in stories now. Women are shown to be capable of problem-solving like men and fighting like men (we still need to grow away from the violence-is-the-inevitable-and-only-solution brainwashing of our warmongering society, but that's another issue). Female characters are often intelligent, competent career women, leaders, or technology experts.

ReplyDeleteMany stories focus on the bond between two women, such as _Thelma and Louise_, _Baby Mama_, _Fried Green Tomatoes_, and _Frozen_. True, to make it more palatable to our patriarchal culture, and to not risk veering too far from their tried-and-true formula, Disney did throw in the romances for Anna (turning the robber girl with the reindeer into Kristoff!). :b Still, _Frozen_ is, after all, primarily about women helping women, despite your prediction.

Yet, I believe I have yet to see a woman character rescue a man in distress, even though female surgeons, paramedics, firefighters, and police officers do it in real life regularly. Men are still shamed for being “needy,” “weak,” and “less than,” like we second-class female citizens, when in need of help. So far, the media has progressed to often showing women contributing to the fight as part of a superhero team, or taking turns saving a man, then having him rescue her back, and so on (I remember _Once Upon a Time_ doing this with Snow White and Prince Charming).

Another area where growth is needed is character sex proportion. There are tons of movies and shows populated entirely or mainly by males, but few that are primarily female, or even half-and-half. I just realized that, even in Disney animated movies with a female protagonist, nearly all the animal and human sidekicks and supporting characters are male.

At least with _Mulan_, _Brave_, and _Frozen_, getting a man isn't the heroine's focus. I'm eagerly awaiting an American mainstream movie in which the heroine rescues a man, period, with no need for him to save her back to make it “equal.” _Frozen_ could have been that movie, but Disney felt America wasn't ready, and they were probably right. The latest _The Little Princess_ was lovely, but boys were turned off by the title, even though many probably would have liked it if they had given it a chance. ////Bunny kisses for all!

P.S. As I was reading summaries of Andersen's tales to begin testing my hypothesis, I discovered that the trolls in _Frozen_ come from another tale, “The Hill of the Elves”! I wonder if bits of other Andersen tales made it into the movie as well? I'm sure the Disney researchers were thorough.

P.P.S. And apparently the horror movie _The Puppeteer_ is inspired by an Andersen short story of the same name! I've only read the main tales, but, judging by the summaries, it looks like I haven't missed out on anything.