(Disclaimer: If you’re a hardcore Sherlock fan who sees no problem with Irene Adler’s portrayal in the show, this may not be the post for you. Here, there be dragons. Also, NSFW content.)

Imagine, if you will, a modern adaptation of “A Scandal in Bohemia” as an exploration of the spread of digital information set against the backdrop of a status-obsessed high school. Sherlock Holmes is the weird kid, an adolescent Encyclopedia Brown with a drug problem who has recently gained notoriety for acting as a consultant for the local police. John Watson is his straight-laced best friend, recently injured in an Army Cadet exercise. Irene Adler is the former choir star who regularly misses class to visit exotic climes. Last year, she had a fling with a popular student known in the drama department as the King of Bohemia, who has told his new girlfriend’s strict parents that he is saving himself for marriage. When Irene threatens to email incriminating pictures to the king’s potential future in-laws, the king knows it’s time to bring in the big guns, in the form of Sherlock Holmes.

Will Holmes prevail? Will we want him to? No, because this Irene is a woman wronged, whose trust and home are violated, whose quest for revenge ends when she decides to be the bigger person, and whose actions prove her more than equal to the greatest detective in literature. You know, like in the original.

Our point with this exercise is this: it’s not that hard to make a modernized adaptation faithful to the spirit of the original work. Looking at “A Scandal in Belgravia,” however, you’d think it was impossible.

(Full disclosure: Although Ashley has seen every episode of Sherlock, I’ve only watched this one. She’s out of the country right now, so I’ll limit my comments to observations about this specific episode.)

So, to quote the King of Bohemia, the facts are briefly these: Sherlock and Watson are caught in a stand-off with Moriarty when Moriarty gets a phone call that convinces him to let them go. We learn that the mysterious caller was a woman, and we soon find out that this is the woman when Sherlock is hired to find sexually explicit pictures taken by the dominatrix, Irene Adler, of herself and a young, female member of the British royal family. Hijinks (that we will detail a little further on) ensue and Irene keeps the photos from Sherlock’s grasp. So, technically, the “Scandal in Bohemia” section is finished about half an hour in. After this, the episode essentially becomes a piece of particularly misogynistic fanfiction.

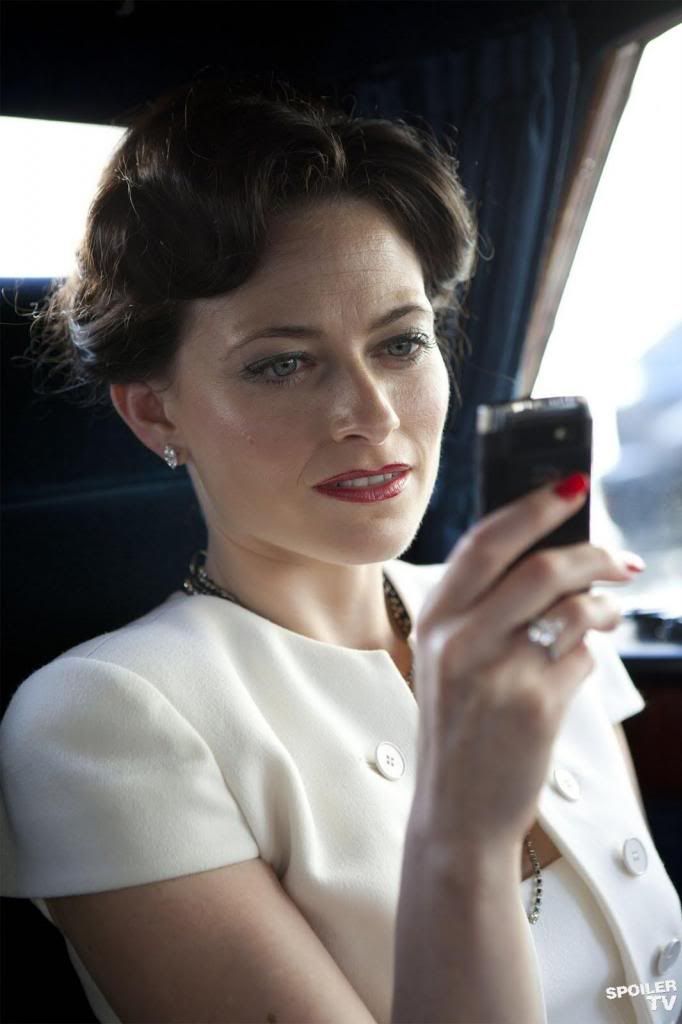

Let’s start again because, as Sherlock Holmes states, “it is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.” Irene Adler is introduced as a hand with carefully manicured, long, crimson nails clutching a cell phone. When she walks further into the shot, she is wearing black lingerie. Her head is never revealed, showing her to be an anonymous body. She enters a doorway through which we can see the legs of a woman shackled to a bed. Accompanied by the crack of a whip, she says to the woman on the bed, “Well now, have you been wicked, Your Highness?” The shackled woman replies, “Yes, Miss Adler.” And that’s how we meet Sherlock Holmes’ intellectual rival: as a body.

This becomes a recurring problem. Before she meets with Sherlock, there is a scene juxtaposing their separate preparations. Both consider their chosen outfits to be a kind of armour, but while Sherlock remains fully clothed as he puts together his clergyman costume, Irene is again shown in loose, barely there robes and revealing gowns. While she gets ready, the camera lovingly captures (in fragmenting close-up) the sensual movements of her girlfriend/personal assistant/person whose role I’m pretty sure is never really explained applying her eyeshadow and lipstick. Her assistant, Kate, asks what she will be wearing, and Irene answers, “My battle dress.” Which, it turns out, is nothing at all. She throws off Sherlock’s game by arriving naked, relying solely on her body to blast through his defenses. As if all this weren’t enough, the code to Irene’s safe turns out to be her measurements. Because she describes the phone hidden in the safe as her life, her body is literally the key to her life.

Like many of the other people who have commented on this episode, we have no problem with the fact that she’s a sex worker. What we do take issue with is the way in which sex and sexual control form almost the entirety of her character. When she talks about using her connections with specialists or influential people, the connection was invariably forged on the job; when she says she knows someone, the implication is always that it’s in the Biblical sense. She even reframes intellect in these terms, stating that “brainy is the new sexy.” And the thing is, she is brainy, but every time she or Sherlock accomplish some impressive intellectual task, she immediately links it to sex. The best example occurs late in the episode, when Sherlock cracks the code to discover the flight information of a doomed airplane; to show her appreciation for his skill, Irene states, “I would have you right here, on this desk, until you begged for mercy twice.”

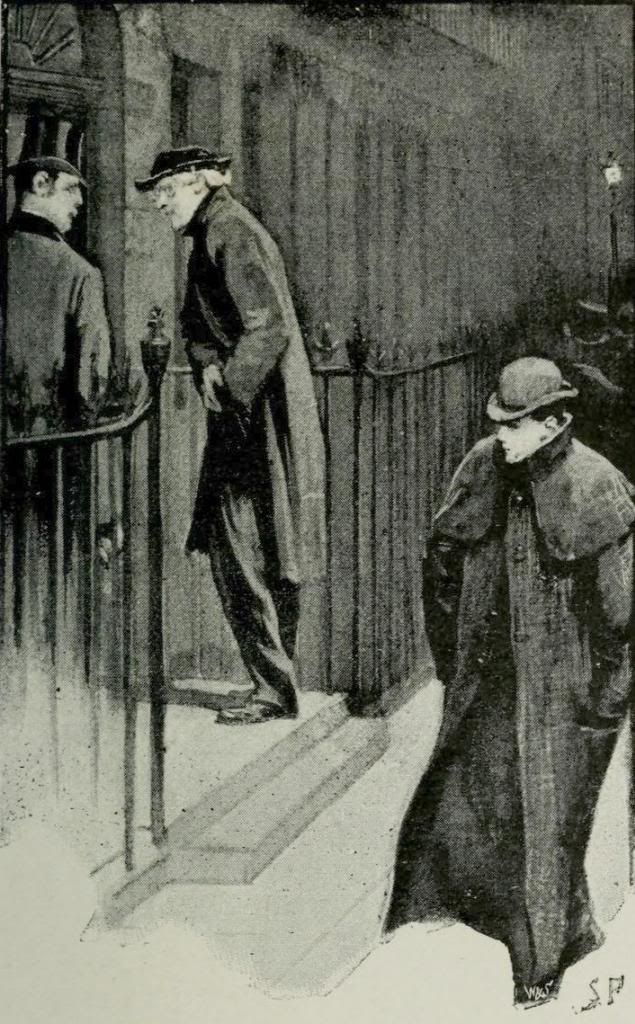

There is another problem with this conceptualization of Irene Adler’s power. In the original story, most of the punch of Sherlock’s defeat comes from the fact that she beats him at his own game. He is known for using his powers of deduction; she deduces either that the kerfuffle outside her house was staged or that Holmes was in disguise (or both). He meets her in disguise, so she wears one to follow him and confirm his identity. In Sherlock, however, Irene is constantly manipulating his apparent discomfort and inexperience with sex. It is the difference between besting a master in their area of expertise and striking an easily exploitable weakness. One’s just more impressive than the other.

Comparing these two methods, I find it interesting that the original story complicates Irene’s deduction by portraying her as unwilling to believe that an old clergyman could be working against her. Essentially, she almost doesn’t win because she wants to think the best of people and assumes that an old man who was injured trying to help her is a decent human being, not an agent of her enemy. The Sherlock Irene, by contrast, messes with people’s lives by faking her own death and threatens to incite scandal just for the hell of it.

Here’s the deal: I love female characters with dubious moral codes. Give me all the ladies with checkered pasts and compelling, human weaknesses. What I don’t like is the fact that modern (almost always male) writers cannot conceive of a powerful, intellectual woman like Irene Adler being genuinely decent. The scandal in the original story would have been the result of the king doing Irene some cruel wrong, which may or may not be the wrong of carrying on a long-term, sexual and romantic relationship and then pulling the plug because Irene was not of his social status, a fact that he knew going into the relationship. Any payback she exacted could easily be justified as karma.

In addition, the context of the original story has people constantly violating her privacy and invading her home in order to steal her personal belongings. It’s not wrong to be a bit annoyed by that. Still, she doesn’t ruin the king’s life and even makes a point of being the better person. She’s a thoroughly decent human being. In modern adaptations, however, she’s made into a manipulative love interest and antagonist because obviously a powerful woman has to be evil. Or, at the very least, morally inferior to Sherlock Holmes.

What proves that this adaptation misses the point of the original story is not the fact that its Irene is morally inferior to Holmes, but that she is intellectually inferior to him. While most of the episode is offensive, it is in the climax that it proves itself offensively wrong.

First, Irene loses. The whole point of the character in the original depends on her victory, but this Irene does not triumph. She’s not even an independent agent, working instead with Moriarty. Even with the assistance of a man, she cannot beat Sherlock, who bests her in the nick of time and then gloats about it, literally making her beg for protection. Instead of Sherlock learning a lesson in humility, Irene is humiliated.

Beyond the obvious problems with this ending in terms of Irene’s depiction, it has disastrous consequences for Sherlock’s character. Sherlock has to lose to Irene, if for no other reason than that it builds his character. It makes him human and shows him to be fallible. It makes the times when he wins matter more, because we now know that he can lose. It takes him down a peg and makes him acknowledge the value of others. It forces him to reassess his assumptions, ultimately helping him to eliminate his blind spots and become a better detective.

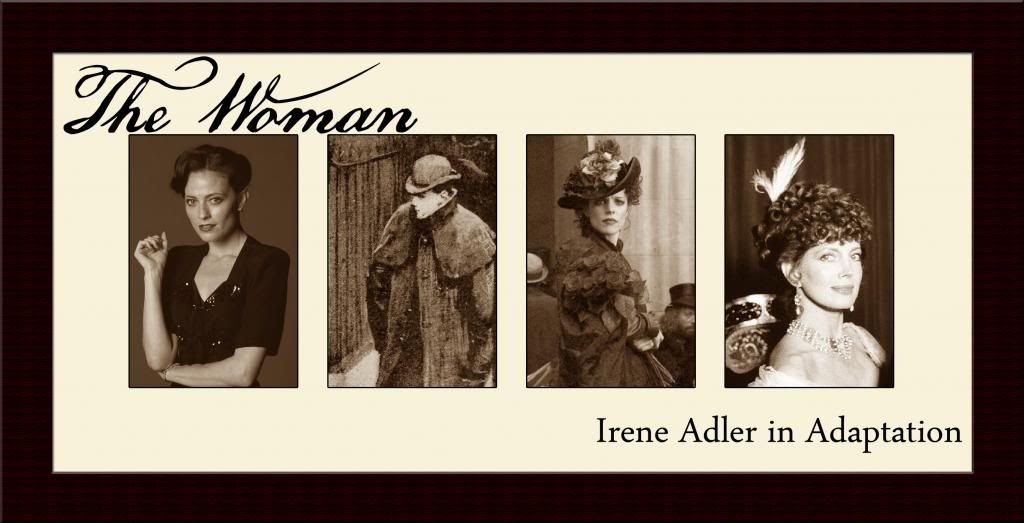

This brings us to this adaptation’s treatment of “the woman.” The title is not originally bestowed by Sherlock on Irene as a mark of respect; instead, it’s Irene’s self-constructed business persona. Sherlock’s brother, Mycroft, suggests that Sherlock’s use of the title could be either a sign of loathing or a salute. The fact that the first is even an option shows that this adaptation went off the rails.

Even the possibility that it is a sign of respect seems unlikely, as Sherlock spends much of the episode being extraordinarily condescending to her, with one brief respite when it becomes apparent that she has played him. In the climactic scene, however, his superiority is restored. He solves the code on her phone and then lectures her about the reason why she lost. As he observes, “this is your heart, and you should never let it rule your head.” Irene Adler is defeated by her love for Sherlock Holmes. She falls victim to her womanly feelings and finds herself beaten by Sherlock’s masculine intellect. It is too awful for words, except perhaps these: if your adaptation of a 120-year-old story has a more antiquated formulation of gender roles than the original, you need to take a long, hard look at your life.

Finally, because a sandwich just isn’t a sandwich without the tangy zip of Miracle Whip, an analysis of “A Scandal in Belgravia” isn’t complete without some mention of its awful treatment of Irene’s sexuality. Not only does Irene fall in love with Sherlock, she does so while seemingly identifying as gay. When she assumes that Watson and Holmes are in a relationship, Watson tells her that he isn’t gay, to which she responds, “Well, I am.” Upto this point, she appears to be portrayed as bisexual, having had relationships with both men and women. With this scene, however, there is a strangely deliberate attempt to turn this into the story of a lesbian who falls in love with a man.

One could make the argument that sexuality is fluid, and that love defies gender. Of course, on television, that’s only ever true of young, attractive women whose queerness is often fetishized before they invariably fall into a heterosexual romance. There is no attempt made here to explore the nuances of sexuality. There is only an incredibly dubious heterosexual romance between an ostensible lesbian and a man often read as asexual, which ends with the man saving the woman as if she were a damsel in distress. It’s the opposite of progressive.

And this is ultimately our problem with this adaptation: for a modern Sherlock Holmes, it seems positively primeval.

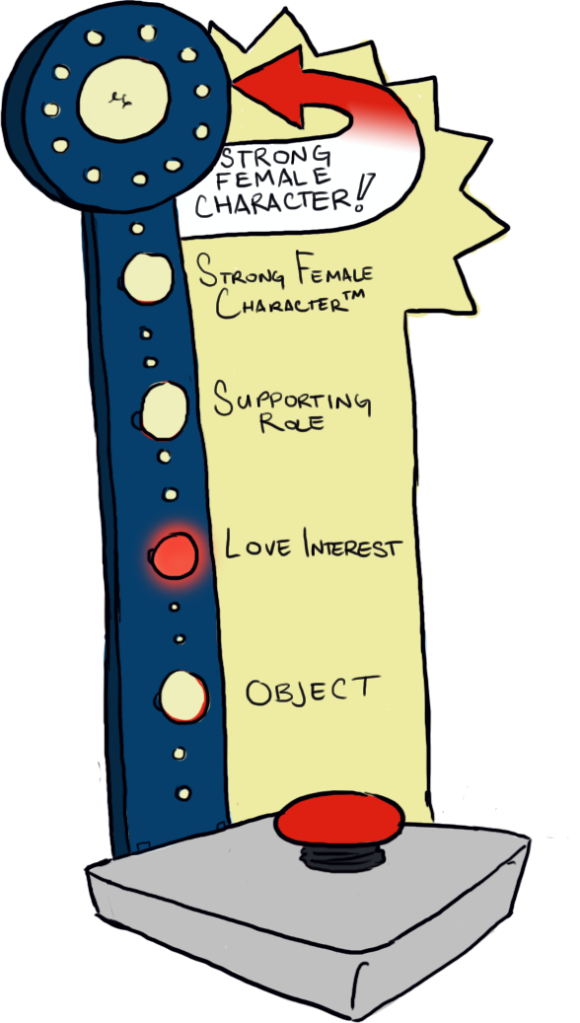

Verdict: Strong Female Character™

And remember, we strongly recommend that you check out our new Monday posts, helping you with gift ideas for your friends, your family, and yourself from now until Christmas.