Canada is known for many things: breathtaking natural beauty, an over-dependence on maple syrup, and a population whose famous humility makes way for brief bouts of patriotism only once every four years, when we cheer for the gifted athletes we usually ignore and the professional hockey players we watch almost constantly. We are not, as a rule, celebrated as the home of fantastic feminist television shows.

However, with the international success of the homegrown drama Bomb Girls, that’s beginning to change. Set during the Second World War, Bomb Girls chronicles the trials and tribulations of life on the home front for the women of Victory Munitions, a bomb factory in Toronto. At work, at home, and at play, these women simultaneously struggle with the sexist standards of their time and bask in the new freedom allowed them while the men fight overseas.

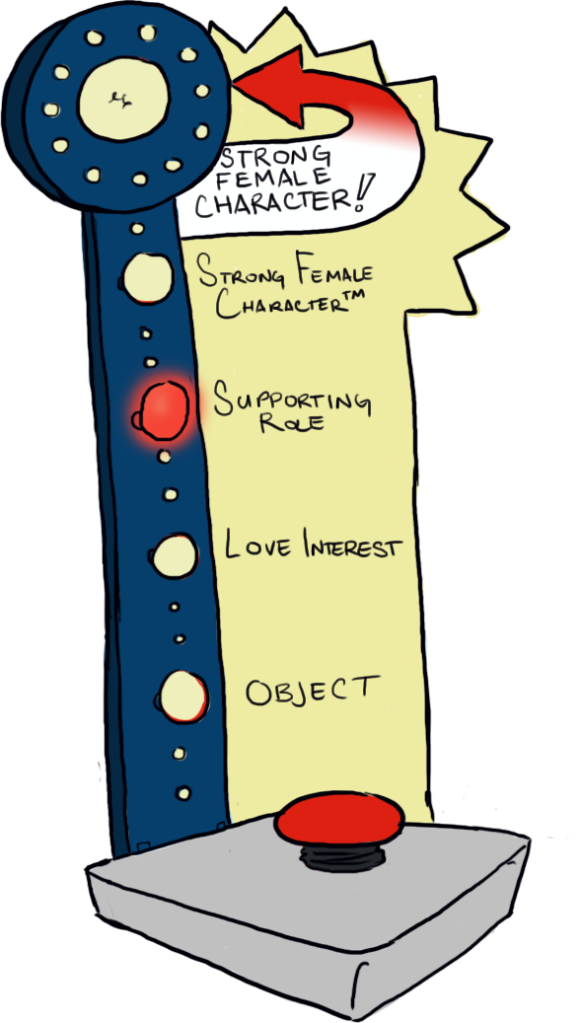

I mentioned in Monday’s post that this show passes the Bechdel test twice in the first three minutes of the first episode, but what is even more notable is that it holds to this pattern for the remainder of the first season. Bomb Girls is precisely the kind of show that would exist in a post-Bechdel test cultural climate, in which women in the media are shown to be thinking, feeling people with important relationships with other women, all of whom have full lives that don’t revolve around men.

(Note: We will only be covering the first season in our analysis. We have, however, timed these posts to coincide with the release of Season Two in Canada, so once you’ve bought and marathoned the first season on DVD, there will be bright, shiny, new episodes waiting for you.)

Lorna Corbett

We begin with Lorna Corbett, the blue shift matron at Vic Mu, who is just about the only person in management who seems to understand how to run the place. It is her job to ensure order in her shift and to inspect her workers for materials that may spark in the very literal powder keg in which they work. Her boss, Harold Akins, reduces her job to a simple task, exclaiming, “For God’s sakes, all you have to worry about is dressing the girls for their shifts.” But Lorna actually does much more. She asks that the factory implement a comprehensive sexual harassment policy and goes on to write it herself. When a bad bomb injures three male workers during testing, she takes the women’s suggestions for improvement to Akins. She tells him to publish them in a report and take the credit for increasing safety and productivity; in exchange, she asks only that her scapegoated worker be rehired.

In these two instances, and in many others, she demonstrates that she is committed to protecting her girls. The best example occurs near the end of the first episode, when Lorna appeals to a doctor to give a grievously injured woman worker the same treatment that he would give the higher priority soldiers. She gives an impassioned speech: “You can’t let her leave here deformed; it will destroy her future. … Vera is a soldier. Vera risked her life every day to help win this war. Do not turn your back on her. If you want to see our boys with bullets in their guns and bombs in their planes, you will show her the same respect. … Now go in there, and book the operating room, and you do the surgeries, no matter how expensive or lengthy. You do your best for that girl.” Lorna refuses to let women’s role in the war be dismissed and their work devalued; instead, she argues that they are instrumental in the men’s success and should therefore be treated with equal care.

Lorna knows very well what it means to contribute to the war effort. She is the mother of three grown children, two of whom are fighting across the pond while she and her daughter do their part at home. She is also the wife of a World War I veteran, whose experiences during the Great War left him crippled, both physically and emotionally. The show takes this opportunity not only to flesh out the well-worn character of the dissatisfied middle-aged woman, but to explore the effects of PTSD on the affected person’s family.

As her husband’s character becomes increasingly complex, we discover what Lorna has had to live with for twenty-five years. Bob has a drinking problem and a tendency to be brutally honest in a way that comes across as callous. He refuses to have sex with her and chooses to complain about the extravagance of buying a whole pot roast rather than praise Lorna for making it. He’s not all bad, however. His observations, cynical as they may be, are often correct, and his decision to revisit the trauma of his wartime experience in order to write convincing letters for Edith’s children is admirable. When it comes to their marriage, however, things have gotten so bad that Lorna becomes suspicious when he displays any positive emotion.

From Lorna’s perspective, the problem is that Bob has never made any effort to move on from his traumatic experience, choosing instead to view the world “through the lens of a few terrible months [he] had twenty-five years ago.” He seems to prefer to wallow in his pain rather than acknowledge the things they have accomplished since the war. While he remained isolated in his pain, she tried to convince him to let her in, explaining that “[she] asked, [she] hinted, [she] tried, and then finally, [she] gave up.” She has been trying to re-forge a connection for decades, and it’s understandable that she would resent him when he finally makes an attempt to do the same.

Her relationship with Bob also explains why she is so determined to help Vera. Faced with the prospect of seeing another person in her life lose themselves to depression, she fights back. She has to make Vera what Bob never allowed himself to become: a person who lives after not dying.

Unfortunately, most of Lorna’s good advice is reserved for other people. Just as she makes it her job to protect her girls, she also considers it her duty to protect her country. In the first episode, she begins a campaign to get a materials controller, Marco Moretti, ousted from Vic Mu based solely on his Italian heritage and Italy’s connections to Hitler. She accuses him of being an enemy spy and then spends most of the first three episodes trying to prove her suspicions. She believes that people who have done nothing wrong have nothing to hide, and any investigation will necessarily find them innocent. Implicit in this notion is the idea that if you are found guilty of something, you must have done it. Eventually, she reports him to higher military authorities, which leads to rumours of his being taken to an internment camp. It is only when she shares an awkward family dinner with Marco and his mother that she begins to relinquish her fear and comes to appreciate their cultural differences, as well as the flaws in her worldview.

While Lorna claims that her actions are driven by the circumstances of global conflict, she proves that, in this case, the political is personal. Smoking out an enemy spy allows her to feel like she’s helping to protect her sons; the same rationale motivates her to make the bombs that will kill other mothers’ sons. When she sees Marco with his mother in his home, she can no longer pretend not to see him as a person. Unfortunately, this realization coincides with the discovery of their mutual attraction. It seems that Lorna’s misuse of her power as a native Canadian to banish an Italian threat was also an attempt to banish the temptation that threatens her family and marriage; she had to neutralize what she viewed as a threat to both her home country and her home. This is further complicated by the fact that Lorna ends up having sex with Marco and becoming pregnant with his child, willingly letting him into her life.

This all brings us to the issue of sacrifice. When asked to deliver a speech on Armistice Day, Lorna chooses as her focus the topic of individual sacrifice on behalf of the greater good. While she explicitly links this concept to the efforts of soldiers in both wars, she also acknowledges the sacrifices that she and her fellow workers make to support them. Implicitly, she also talks about herself. Early in the speech, she delivers a line that she wrote in an earlier scene; the repetition suggests that it is intended to draw our focus. As she says, “We are all asked to make sacrifices, and while not every sacrifice is rewarded, it is our duty to do so.” It seems as if Lorna is speaking about her marriage, twenty-five years of living with a distant partner in order to raise three children, two of whom she has offered to her country. By the end of the speech, however, she seems to be looking to the future: “Sometimes, you know when a thing is right. What’s a few small sacrifices on our part when we stand to win back the happiness and freedom we deserve?” She sees herself as deserving of love and affection. She sees herself as deserving of a life that takes into account her needs.

This all changes when she learns of the pregnancy in the next episode. After the positive test comes back, she breaks down in front of Marco, saying that she’s a horrible person who deserves this punishment for all of the awful things she’s done. She laments, “I thought it was finally my turn; I’d get my life. And now it’s over.” She has come to the conclusion that she’s not the hero, doggedly pursuing the enemy; rather, she is the villain, paying for her crimes.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

Edith McCallum

Edith is the least developed and, arguably, the weakest character among the six that we’ll be discussing. At the factory, she is Lorna’s right-hand woman, the bridge between her and her girls. In the show, she is the first victim of the war.

Edith is at work when she learns that her husband’s plane has been shot down, and her grief is suddenly made very public. While the show makes clear that the news could have come to anyone, even going so far as to make it seem as if one of Lorna’s sons had died, it is ultimately Edith who collapses with grief. The rest of the season chronicles her attempt to cope with the loss.

Although she gets less screen time than other characters, Edith’s story is a fairly compelling one. She continues to work after receiving the news, taking comfort in her friends and in the activity. Despite the fact that she barely sleeps, she knows that she must support her family and diligently does her job until she is the unfortunate victim of scapegoating after a disastrous testing day. When Lorna tries to justify her firing by implying that she could have done better on the test, Edith defends herself: “Aside from not sleeping a wink since my husband was blown to bits, or worrying how I’m gonna raise two kids, or how I still can’t tell them Daddy’s never coming home... Aside from all that, I can’t imagine what took my head out of the game.” In addition to her grief, she now has to deal with a reputation for incompetence that will prevent her from finding further employment.

Once she gets her job back, she still has to deal with the mess that is her personal life. The rest of her storyline revolves around her refusal to tell her children that their father is dead. Although both Lorna and Bob take issue with her decision, Edith is persistent, trying to protect her children from the kind of pain that she is experiencing. She causes herself more pain, however, in pretending that everything is fine. Helping and hindering her in this pursuit is Bob, who pens letters for the kids in the guise of Edith’s husband before eventually revealing the truth. In a refreshing change, the show doesn’t actively support Bob’s decision to end the charade, but instead has him acknowledge that it was her right to tell them; he apologizes for taking away her agency.

Verdict: Supporting role

Very nice! I really enjoyed your blog throughout all the time I have spent on it.Your post is a great inspiration to those of us who are fortunate enough to not be living life alone because of death or divorce - a reminder to be the best we can be for each other.I am really aknowleged by the content provided by you on this blog.

ReplyDeleteTo know more visit here :- Divorced Selling Home