(Note: For this analysis, I will be referring to the 2003 Director’s Cut of Alien.)

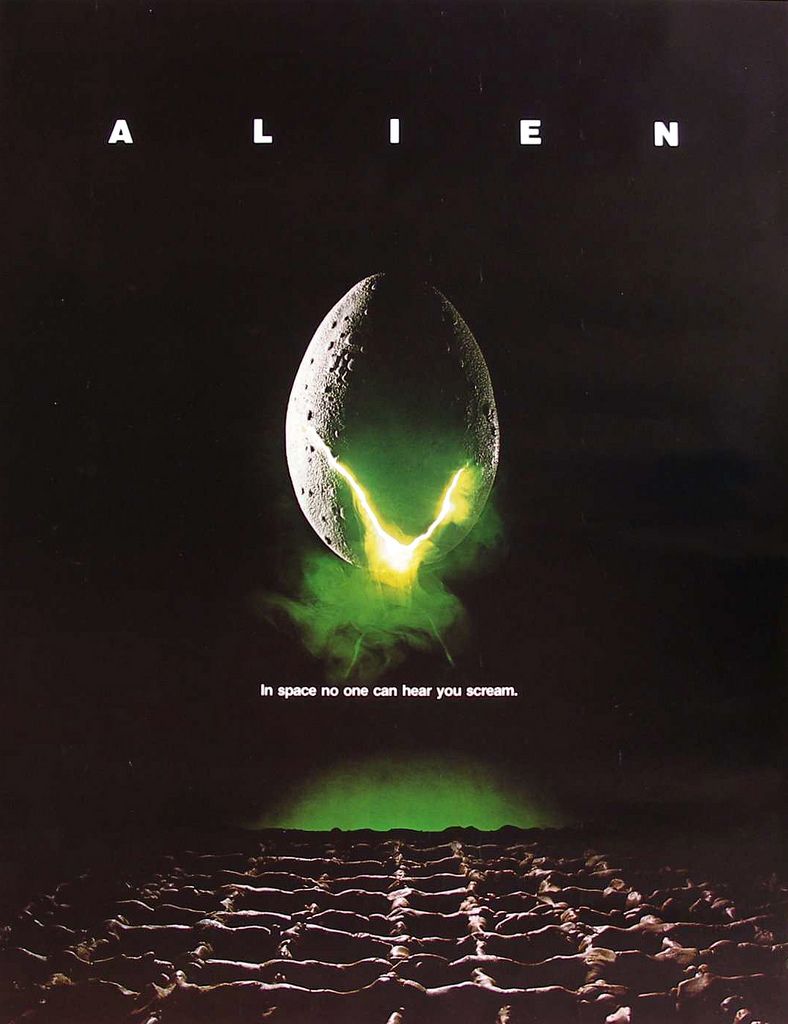

In

the past nine months, we’ve talked about a lot of characters. There are

some we’ve devoted whole posts to, while others were forced to share

space with one, two, or, in the case of the Disney mothers analysis, a

dozen or so other people. But there are some characters too big, too

important, and too iconic to be contained in one post. For that reason,

we’re introducing the Heavy Hitters, month-long discussions of the most

influential female characters in pop culture.

We begin with Lt. Ellen Ripley, who, in her debut in Alien,

is the third officer of the commercial towing vehicle Nostromo, the

sole survivor of said spaceship, and an all-around badass. For those who

have never seen the film, here’s a quick summary. The crew of the

Nostromo wakes up from cryogenic sleep only to find that the ship has

been re-routed far from its usual territory. Already a little thrown off

their game, the crew faces further strangeness when they receive a

transmission from a small planetoid that they assume to be an SOS. They

descend to the planetoid, where the scouting party discovers a ship full

of eggs; one hatches, and the creature inside attaches itself to the

face of the executive officer. Ignoring the company’s quarantine rules,

they bring the alien parasite onboard, where it bides its time before

emerging as a human-sized nightmare and killing everyone but Ripley, who

shoots it into space.

The

first significant point to discuss in terms of Ripley’s portrayal is

the fact that she was not originally intended to be a woman. In the

original script by Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett, they specify that,

while the sole survivor, then called Martin Roby, was written as a man,

“the crew is unisex and all parts are interchangeable for men or women.”

Still, it’s a pretty safe bet that they weren’t planning to be part of

the genesis of one of the first female action heroes.

The

concept of ostensibly gender-neutral casting is something of a thorny

issue. Is a strong female character really a strong female character if

she was originally intended to be a man? Is there more to writing women

than merely taking a male character and having him be played by a woman

(the so-called “man with tits” writing method)? Can male writers write

female characters as complex people without initially envisioning them

as men? Is there such a thing as a major “unisex” role? Should there be?

What

I’m trying to get at is the simple fact that a person’s gender

necessarily affects the way they experience the social world around

them, and this is particularly true of Ellen Ripley. Before she defeats

the alien Xenomorph, she has to confront the patriarchal power structure

that allowed it to get onto the ship in the first place. After the

Facehugger attaches itself to the executive officer, Kane, the scouting

team returns to the ship, desperate to move their colleague into the

infirmary. Ripley, left in charge during the absence of both Captain

Dallas and his second-in-command, refuses them entry on the grounds that

they could infect the rest of the crew. Dallas, who should know the

quarantine procedure, disagrees with her assertion that they would do

the same thing in her position. He is fine with the possibility of

saving one person, even if it means jeopardizing the group.

Ripley’s

struggle with Dallas takes on some heavy metatextual meaning over the

course of the film (at least the part he lives to see). Although the

film initially refuses to reveal its protagonist, focusing in turn on

every crew member as part of the group, the most likely candidate that

emerges is Dallas. He’s a white man in a position of authority; he’s

Hollywood’s second favourite heroic type, after the white, male underdog

who rises to a position of power. He is, however, not much of a hero.

He proves himself an ineffectual leader when he chooses to risk the

entire crew in order to save one person, and when he blindly follows the

Company’s orders and cedes responsibility over the alien to the science

officer, Ash. In both cases, Ripley defies him.

Their

conflict reaches its climax when Dallas outlines a plan to kill the

alien that involves one person flushing it out of the air ducts. Ripley

volunteers, but Dallas takes the job for himself, as if he was somehow

misinformed and thought that he was starring in a typical Hollywood

action flick where he was the lead. At this point, there still remains

the slightest possibility that he could be right, at least until he

fails to use his flamethrower and gets taken by the alien. His capture

and probable death leaves Ripley in charge, of both the Nostromo and the

narrative. With the typical male action hero not only weakened, but

removed from the story entirely (save for a brief scene in which Dallas,

entombed in an alien nest, begs Ripley to end his life, acknowledging

both her agency and his lack of it), Ripley is free to take her rightful

place as the film’s protagonist.

Because

Dallas is ultimately so ineffectual, the real battle between Ripley and

the patriarchy is the one she fights against Ash. Dallas argues against

the quarantine, but Ash is the one who opens the airlock. From this

point on, he becomes Ripley’s primary antagonist. When she confronts him

about the violation of quarantine procedure, she does so by reminding

him that she was the senior officer and that, as a science officer, he

should know to enforce certain rules. She reminds him that she did her

job, even as he failed to do his. After Dallas is captured, she

confronts Ash from her newly inherited position of power, telling him

that he can continue to do nothing. She observes that she now has access

to Mother -- the MU-TH-UR 6000 computer mainframe that operates the

Nostromo -- and states, “I’ll get my own answers, thank you.”

Unfortunately,

the answers are not what she had hoped they would be. The Company wants

the Nostromo to bring the alien back to Earth, and they have deemed the

crew expendable. Ash already knew about this, and, when Ripley attacks

him in rage and desperation, we find out that the reason why he was okay

with human loss is because he isn’t human himself. Suddenly, instead of

woman vs. man, it’s woman vs. robot and woman vs. Company, and his

strength quickly overcomes hers.

This

is arguably Ripley’s darkest moment. In addition to the psychological

blow of learning that she and her crew have been sacrificed by their

employer, she suffers a physical beating at Ash’s hands. Then, to cap it

off, he performs a sort of attempted rape by rolling up a pornographic

magazine and forcing it into Ripley’s mouth. In an article entitled “The Rise of Ripley: Gender and ‘Alien,’ Part 1,” Jordan Poast describes the

symbolism of this event:

This assault bears a dual offense to Ripley’s feminist thrust. Firstly, as an act of male dominance against an independent woman, Ash’s attack is akin to an oral sexual violation because he tries to oppress her by forcing her to swallow (or submit to) the images of female subservience. Secondly, the act silences Ripley, depriving her of the authority that she typically asserts through her voice.

What

also strikes me about this scene is its potential critical function.

The audience sees a complex woman, the character who serves as our point

of identification, quite literally having the sexual objectification of

women shoved down her throat by a machine that acts as the tool of a

corporation. Intentional or not, it reads as a powerful condemnation of

the standard Hollywood practice of portraying women as objects of male

sexual fantasy and, by positioning the audience firmly in Ripley’s

perspective, it shows these images to cause harm to those who consume

them.

Once

Ash is defeated, it’s time for the remaining crew to turn their

attention back to the problem of the alien. Ripley decides to blow up

the Nostromo, while she and her two remaining crew members escape in the

shuttle. As one might expect, the alien kills both of them while

they’re gathering supplies, and Ripley is left alone. She manages to

make it to the shuttle just in time to watch the destruction of the

Nostromo, an explosion that should serve as proof that she successfully

saved Earth from the alien threat. She says as much when she observes,

“I got you, you son of a bitch.”

Except

she didn’t. Here’s where things get really interesting. Ripley strips

down, in what must be a conscious moment of sexualization on the part of

the filmmakers, considering the fact that Ripley has spent the rest of

the film wearing multiple layers, including coveralls. At the same time,

her decision to get undressed makes narrative sense; she’s preparing

for hypersleep, and she’s shedding the uniform of the company that

signed her death warrant. It is also at this most vulnerable moment that

she spots the alien hiding on the shuttle.

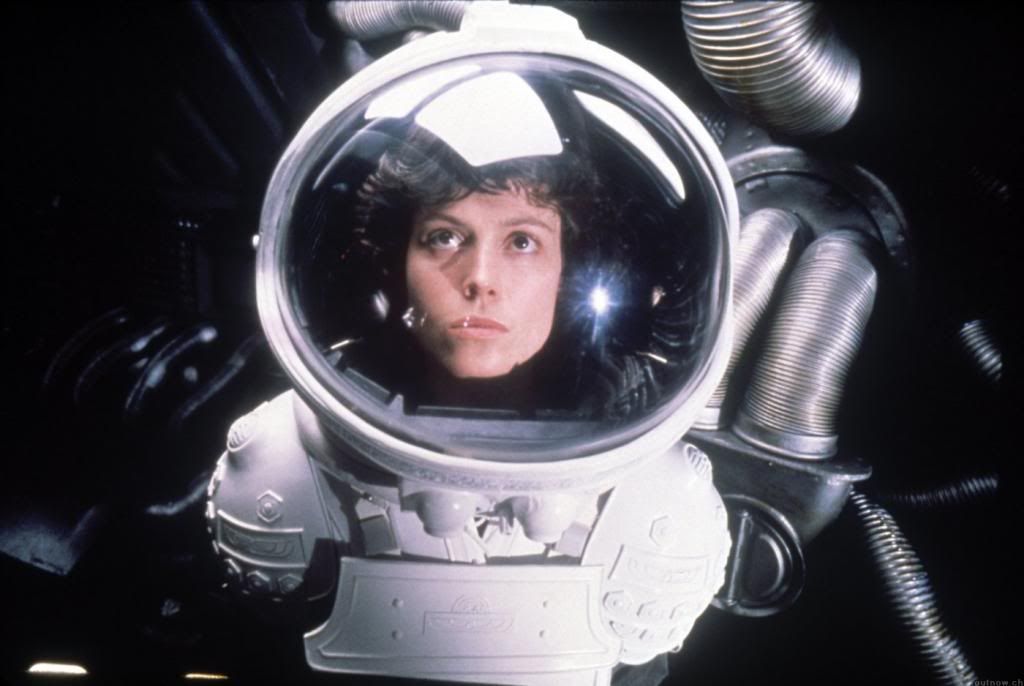

In

the final scene, we see Ripley become a tactician. While she has

already displayed courage, intelligence, and determination, this is

where we see the resourcefulness and planning that come to define her

character in the second film. She quickly and quietly dons a space suit

that resembles a suit of armour, transforming herself from the damsel in

distress into a knight. She fills the cabin with gasses to flush the

alien out of its hiding place, blasts it out of the airlock and, when it

holds on to the hull, shoots it with a harpoon gun. When it still

refuses to die, she fires up the engines and blasts it with heat, then

watches as it floats off into the vacuum of space. Finally, she settles

into her hypersleep pod, ready to return to the civilization she has

saved.

Before

taking her well-deserved rest, she makes a final report, concluding it

with “This is Ripley, last survivor of the Nostromo, signing off.”

There’s a lot of meaning embedded in this statement. Applying a

“survival of the fittest” reading to the film, which is clearly

supported by the film itself, we can argue that Alien

is asserting the superiority of its heroine over the rest of the crew

of the Nostromo. They died because they lacked her caution, her courage,

and her adaptability.

The

real accomplishment, however, is out-living the alien. We know from

Ash’s analysis that the aliens are almost perfect organisms, able to

withstand harsh conditions. We see, in the way that the alien so easily

hunts its human prey, that it is an efficient killer. Ash describes it

as “a survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of

morality,” but, while he attributes its survival to the lack of these

traits, the film suggests that Ripley’s survival is made possible by her

possession of them. Her initial refusal to let the alien onto the ship

was motivated by concern for the rest of the crew. She argues with

Dallas because he blindly obeys the Company’s orders instead of doing

what is right. Even when the ship is about to explode, she spends

precious minutes saving Jones the cat and ending Dallas’ suffering. She

destroys the alien not just to save herself, but because she knows she

needs to keep it from reaching Earth. She survives -- and is worthy of

survival -- because she is interested in more than mere

self-preservation.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

No comments:

Post a Comment