(Note: For this analysis, I will be referring to the 2003 Special Edition of Alien3, written hereafter as Alien 3, because it’s clearly not intended to be Alien Cubed. Then again, it was 1992...)

(Trigger warning: discussion of attempted rape)

Hollywood loves franchises. This summer alone, there is a prequel to Monsters, Inc., a re-imagining of the Superman mythos, and the sixth installment in the Fast and the Furious series. Some series -- such as Richard Linklater’s trilogy of Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and the recently released Before Midnight -- may go almost a decade without a new film, but most modern franchises operate with very short turnaround times. The Lord of the Rings trilogy was released in annual installments, and Harry Potter never went more than two years without making an appearance at the theatre. Even the Dark Knight trilogy only took seven years.

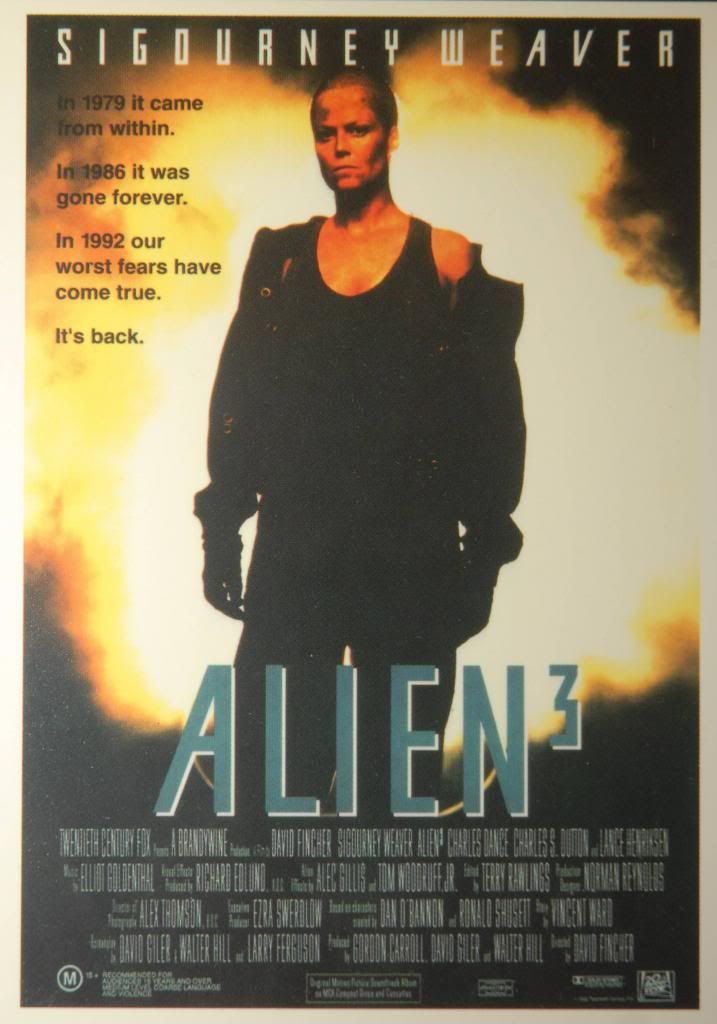

So a franchise like the Alien

series -- written and directed by different creators for each film,

transforming from a horror into an action flick into an existential

thriller into a parody of itself -- seems a bit strange to the modern

viewer. There are only two things that tie the four together and, in

turn, become increasingly tied together: Xenomorphs and Ripley.

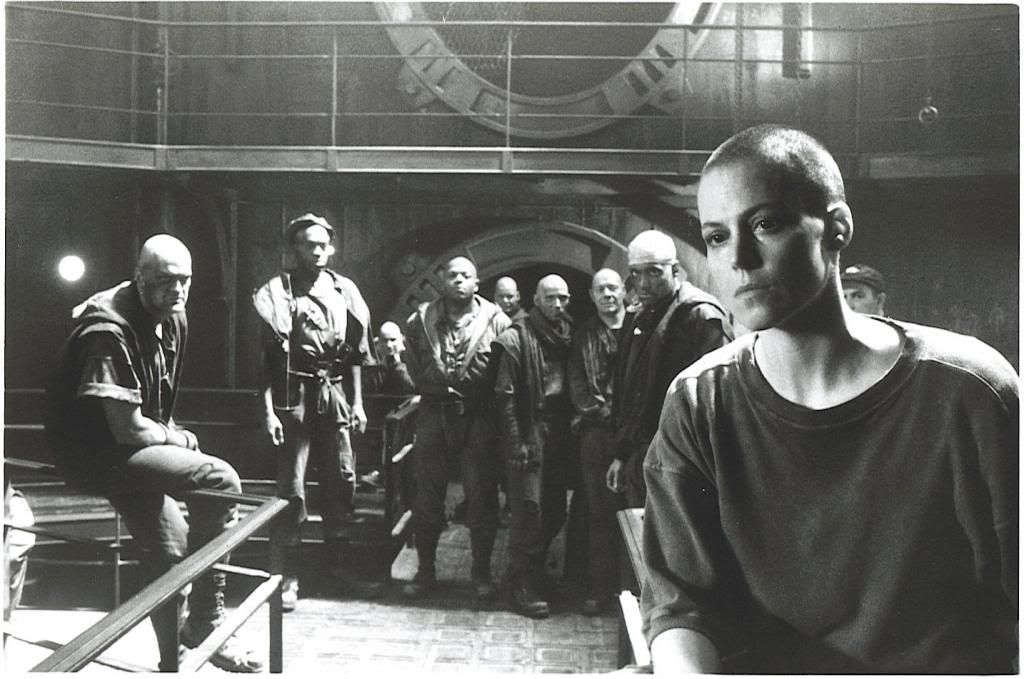

Alien 3

begins with the crash landing of the Sulaco on the prison planet,

Fiorina “Fury” 161, caused by a fire that may have been produced by

alien activity. Once again, Ripley is the sole survivor, making all of

her efforts to save Hicks and Newt completely meaningless; it’s a cheery

place to start a film. Things only get worse when Ripley learns that

the prisoners are a bunch of double Y chromosome men who were put away

for a number of violent crimes, including rape, murder, and child

molestation. Having found God (and lost women) in exile, they view

Ripley as a kind of temptation. Kept in an infirmary “for her own

protection,” Ripley grieves her lost companions as the alien threat once

again closes in.

As

always, before she can defeat the aliens, Ripley must first confront a

human enemy. In this film, that enemy is almost everyone, including our

old favourites, the Company and the male-dominated chain of command. The

latter is represented primarily by the prison superintendent, who

orders Ripley’s imprisonment in the infirmary. He is incredibly

condescending, saying things like “That’s a good girl” and “Get that

foolish woman back to the infirmary.” Luckily, the narrative’s

intolerance for the underestimation of Ripley kicks in, and he is

dragged away by an alien immediately after uttering the second line.

Unlike the earlier films, where Ripley is stymied again and again by men

in power, Alien 3 very quickly weakens and eliminates male authority.

At

the same time, however, it strengthens the men themselves; the film’s

emphasis on the men’s double Y chromosome appears to exist primarily to

emphasize their maleness. Whereas Ripley once fought figurative battles

against the male heroic archetype, the sexual objectification of women,

and the male-dominated power structure of the capitalist machine, here

she fights the men themselves. For these men, who haven’t seen a woman

in years, she initially represents both the apple and the serpent, both

the forbidden fruit and the voice that urges them to consume it. This is

not because Ripley encourages their attention in any way, but merely

because she exists in close proximity to them. When the superintendent

orders her to remain in the infirmary, he explains that he doesn’t wants

a woman walking around, “giving them ideas.” Before a crime has even

been committed, the prison’s inhabitants are in full victim-blaming

mode.

It

should come as no surprise, then, that Ripley is sexually assaulted and

almost raped. While she gathers up the remnants of Bishop, she is

ambushed by a group of inmates who bend her over a railing, cut her

clothing, and prepare to enact an almost ritualized rape. Before they

are able to follow through, however, another inmate, Dillon, attacks

them. He continues to beat on them, claiming that he needs to

“re-educate some of the brothers.” While he does that, Ripley punches

one of them in the face.

There’s

a lot to say about this scene. First, there is the matter of the

rescue. Dillon introduces himself to Ripley as “a murderer and rapist of

women,” but we’re supposed to sympathize with him because he’s

reformed, and because he pummels attempted rapists. Regardless of what

you believe about the rehabilitation of sex offenders and murderers, it

says a lot about a film when it expects us to side with such a

character. It is especially disturbing because the narrative clearly

places Dillon in the deuteragonist role; he is nearly as intelligent and

heroic as Ripley. It is Dillon who gives the stirring speeches to rouse

the men to the fight against the Xenomorph. It is Dillon who refuses to

kill Ripley when she asks, instead telling her that he will kill her

after the alien dies, because he knows that leaving even one alien alive

would have disastrous consequences. He sacrifices himself so that she

can complete this very task. He dies to protect the human race, so a

little rape and murder can be forgiven, right? It’s troubling.

Also

troubling is that fact that Dillon is the one who gets revenge on

Ripley’s would-be rapists, while she gets only a single punch to make an

attempt to re-claim her agency, and she doesn’t even get to punch the

man who was going to rape her first. Later, the same man that she

punched, Morse, helps her to evade Weyland-Yutani’s clutches, so, again,

all appears to be forgiven.

I’m

not saying that the film condones the men’s overtly sexist behaviour.

In one scene, two inmates discuss their plans to approach her, which

includes such gems as “I’d be happy to kiss her ass; I’d be happy to

kiss it any way she wants,” “Treat ‘em mean, keep ‘em keen,” and “Treat a

queen like a whore and a whore like a queen.” Because they are carrying

around a dead, insect-covered animal, we can be fairly certain that we

are meant to interpret their words as disgusting and vile. Still, when

the film only condemns men as overtly misogynistic as this, and expects

us to support characters like Dillon and, to a lesser extent, Morse, it

becomes problematic.

It

also prompts us to ask an important question: Why is it necessary to

include an attempted rape scene in a film about a heroic female

character? Having defeated a whole colony of aliens, is Ripley too

strong, too invulnerable? Does Ripley have to be “brought down a peg”?

Is the loss of her two friends and her adopted daughter not sufficiently

awful, so she needs to have her own body violated? Or is the attempted

rape merely a device to get us to accept a male rapist and murderer as

Ripley’s co-hero, simply because he saved her?

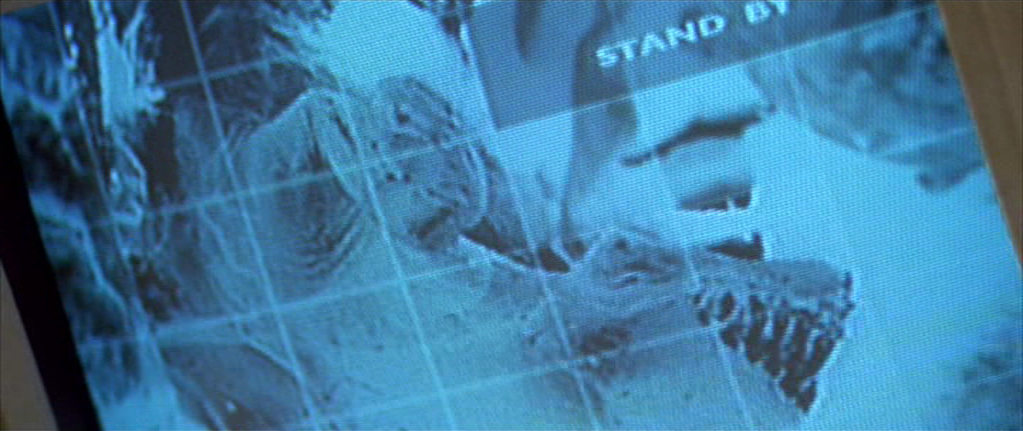

The

only justification I can see for this scene’s inclusion lies in the

contrast between the unsuccessful rape and the successful implantation

of the alien queen. Over the course of the film, we see Ripley becoming

increasingly ill; she feels sick to her stomach, becomes fatigued

easily, and finds that her hands shake uncontrollably. When she

undergoes a scan to diagnose the problem, she learns that there is an

alien queen growing within her. She describes the situation in terms

that link the alien implantation with unwanted pregnancy resulting from

sexual assault: “I was violated, and now I get to be the Mother of the Year.”

The

significance of this development, in terms of both Ripley’s character

and the series’ themes, cannot be overstated. We know from the first act

of Aliens

that Ripley’s worst fear is becoming an alien’s host. The nightmare we

witnessed showed the alien bursting from her chest while she lay in a

hospital bed, and that film’s theme of motherhood allows us

retrospectively to view the scene as an unnatural birth. More than

death, Ripley’s fear is giving life to a creature that will bring death.

For

a person who values her agency and her mission, this situation is

particularly difficult to face. Ripley has basically made it her life’s

work to eradicate the Xenomorphs, and now, against her will, she has

become the potential grandmother to a whole race of killer aliens.

Instead of destroying the aliens, she is helping to create them. What

makes this even worse is that she had no opportunity to fight back; she

was attacked in a moment of vulnerability and had her agency stripped

from her.

Ripley

concludes that the only way to regain her bodily autonomy is to destroy

her body. Initially, she asks Dillon to kill her, echoing a request she

made of Hicks in the previous film. He refuses, saying that he will

only end her life after she destroys the Xenomorph that has been hunting

his men. She is the only person left alive who can annihilate the

aliens, and she must complete the task she set herself before she can

end her suffering. What is interesting about this deal is that the

narrative does not allow it to come to fruition; Dillon sacrifices

himself before Ripley kills the alien. Ripley is left to decide whether

she will remain a vessel for the harbinger of humanity’s destruction or

finally relinquish her “sole survivor” status. The narrative forces her

to take her agency back, just in time for the final showdown.

In

the first two films, there are generally two possible outcomes: Ripley

will live and eliminate the alien threat, or Ripley will die and the

Xenomorphs will wipe out humankind. Either Ripley will win, or

Weyland-Yutani will have its prize. In this final confrontation, Ripley

comes face to face with a team sent by the Company, who claim that they

can retrieve the queen inside of her without causing her harm. They tell

her to “let [them] deal with the malignancy,” as if the creature were a

cancerous tumour. They promise her that they will destroy it, though

she and we know that that is unlikely. Suddenly, the script has shifted:

Ripley can live, so long as she allows the alien an opportunity to

survive, or she can eradicate the Xenomorphs, as long as she is willing

to sacrifice herself. She chooses the latter.

As

Ripley throws herself into the furnace, she assumes a crucifix pose,

becoming an explicitly Christ-like figure in her moment of

self-sacrifice. Yet, even as she assumes this heavenly aspect, she falls

into what appears to be the fires of Hell. It’s an image rife with

symbolism, and you could view it in a number of ways. Personally, I’ve

chosen to interpret the infernal furnace as the rather hellish Alien: Resurrection and

Ripley as the character herself, left to burn in the flames of

incompetent writing until she is an unrecognizable mass of tissue that

might once have been a hero. Of course, that’s just me.

If we ignore the fourth film and treat the Alien

series as a trilogy, it allows us to read Ripley’s heroism as part of a

long tradition, dating back to the Anglo-Saxons. That’s right; I’m

telling you that Ripley is Beowulf. It’s not a perfect fit, but there is

a fascinating parallel. In the first film, she takes on a single,

mysterious monster who preys on her crew and, in so doing, establishes

herself as a hero. In the next film, she destroys the monster’s mother, a

creature who was well within her rights to seek revenge for the deaths

of her offspring. In the third film, she faces a foe known by one of the

inmates as the “dragon.” Like Beowulf, who is an old man when he fights

the dragon, Ripley is weak, a shadow of what she once was. She can

vanquish her enemy, but, in the end, her life is also forfeit. Her death

leaves her people vulnerable to future attacks; dying a hero doesn’t

make you any less dead, and a dead champion can champion very little.

Verdict: Actual strong female character (even if the film’s treatment of women in general is dubious at best)

Awesome analysis! I think I agree on pretty much all accounts, especially the connection between the attempted and completed sexual assaults by the prisoners and the alien, respectively. I actually wrote an entire speech dedicated to feminism in science fiction last semester, and I focused a large portion of it on the role of motherhood in James Cameron's Aliens. The Alien series is such a valuable sci-fi examination of sex and gender.

ReplyDelete