In a series that unfolds like a video game, we would be remiss if we didn’t discuss the boss battles. By this, of course, we mean the evil exes.

Envy Adams

In Natalie V. “Envy” Adams, Bryan Lee O’Malley traces the rise of a superstar and the fall of a fairly decent human being. When we meet Natalie in a flashback, she is an anime fangirl who wears baggy hoodies and dislikes parties. Over the course of her relationship with Scott, she gives up her fannish obsessions, selling her prized possessions for clothing and accessories; changes her name; stops remembering relationship milestones; doesn’t bother hiding her probable cheating; and makes all the decisions for the band they started with Stephen Stills, even forcing Scott to switch instruments. Hers is a classic transformation for the sake of money, fame, and power.

Well, money, fame, power, and a guy. Envy appears to be yet another example of what can go wrong when a woman builds her life around a man. She is completely devoted to Todd, and this makes her blind to his flaws and his transparent lies. She believes that his gesture of love -- punching a hole in the moon -- demonstrates an equal devotion. She believes that gelato is vegan, because Todd says so. Even after she has discovered his infidelity, she believes on some level that Todd didn’t deserve to be defeated. Finally, in the scene in which she departs from Toronto, we catch a glimpse of Natalie, once again clad in a hoodie, taking this opportunity to remake herself without a male influence.

Except, of course, that she doesn’t. The next time we see her, she is preparing to debut her solo album under the watchful eye of Gideon Gordon Graves, Ramona’s seventh and most evil ex. She is intensely fetishized, as he mentions his tendency to dress her up like a Barbie in order to achieve sexual fulfillment. She has been reduced from a woman in control, determining the conditions for Todd and Scott’s battles, to a sparkling bauble for Gideon to play with.

It’s difficult to resist the symbolism that emerges in these last few moments with Envy. Gideon has dressed her in a butterfly outfit, as if to represent metamorphosis and flight. However, he literally removes her wings in order to get to the sword he concealed in her outfit, leaving her in a “sexier dress.” She is clearly reduced to a mere object. Bizarrely, though, by the end of the final battle, she is once again left on her own, and she retains some form of power; using her song, she releases the six potential girlfriends Gideon had locked away. It’s a strange moment, because it seems like Envy’s selfish need to perform nevertheless has positive consequences.

This is one of the problems with Envy: she is difficult to figure out. She has a shifting identity, being both Natalie and Envy to varying degrees throughout the series. The one thing that is clear about Envy is that our view of her is clouded by Scott’s perception. She has the power to literally make him fall to pieces. For the duration of her first phone call with Scott since their break-up, the visual style of the comic changes. Suddenly, the page assumes a fragmented appearance, with smaller panels in a 3x3 format depicting Scott’s memories of Envy interspersed with the scattered pieces of his body, separated by the gutters between panels. His self is actually torn apart.

So

it’s hard to consider his point of view to be objective when it comes

to Envy. In the sixth volume, Envy says as much: “You make me out to be

some kind of villainess. We were practically kids when we dated, Scott, and it’s not like you

were some paragon of virtue.” She claims that Scott broke her heart,

just as she broke his, and reminds him that he was the one who started

that final argument. Scott needed not to be the bad guy in their

relationship, so he made Envy suit the role.

So

it’s hard to consider his point of view to be objective when it comes

to Envy. In the sixth volume, Envy says as much: “You make me out to be

some kind of villainess. We were practically kids when we dated, Scott, and it’s not like you

were some paragon of virtue.” She claims that Scott broke her heart,

just as she broke his, and reminds him that he was the one who started

that final argument. Scott needed not to be the bad guy in their

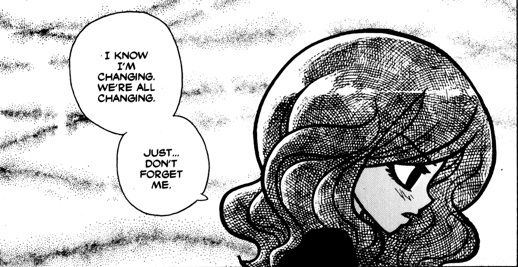

relationship, so he made Envy suit the role.The concept of perception is further complicated by a statement Envy makes at the end of this conversation: “I know I’m changing. We’re all changing. Just... don’t forget me. This is the only me he knows...” This is an issue that goes beyond the problematic aspects of Scott’s suffocating perception that we brought up in our discussion of Kim. Guilty of papering over real events with his more convenient memories, Scott is being entrusted with the preservation of Natalie V. Adams. He must keep an entire person alive.

What

troubles us -- and what we’re pretty sure is supposed to trouble us --

about this line is the way it frames and genders memory. Scott’s story

involves him having to look beyond his own straight, white, male

narrative in order to acknowledge the truth of other viewpoints. What

are the implications, then, of Envy entrusting him with her self before

he has seen the error of his ways? Indeed, what are the implications of

allowing a woman’s identity to be maintained or determined by a man? In

addition, it’s problematic not only that Scott is made responsible for

Natalie, but that Gideon is seemingly creating Envy. Scott is therefore

protecting her past self from Gideon’s controlling influence. Unlike

Ramona, who finds a way to save herself using an army of Ramonas, Envy

is defined by men.

What

troubles us -- and what we’re pretty sure is supposed to trouble us --

about this line is the way it frames and genders memory. Scott’s story

involves him having to look beyond his own straight, white, male

narrative in order to acknowledge the truth of other viewpoints. What

are the implications, then, of Envy entrusting him with her self before

he has seen the error of his ways? Indeed, what are the implications of

allowing a woman’s identity to be maintained or determined by a man? In

addition, it’s problematic not only that Scott is made responsible for

Natalie, but that Gideon is seemingly creating Envy. Scott is therefore

protecting her past self from Gideon’s controlling influence. Unlike

Ramona, who finds a way to save herself using an army of Ramonas, Envy

is defined by men.It almost seems disingenuous to mention the film version here, because she’s nothing more than a caricature. She doesn’t even get to fight. She does, however, get to rock a Metric song.

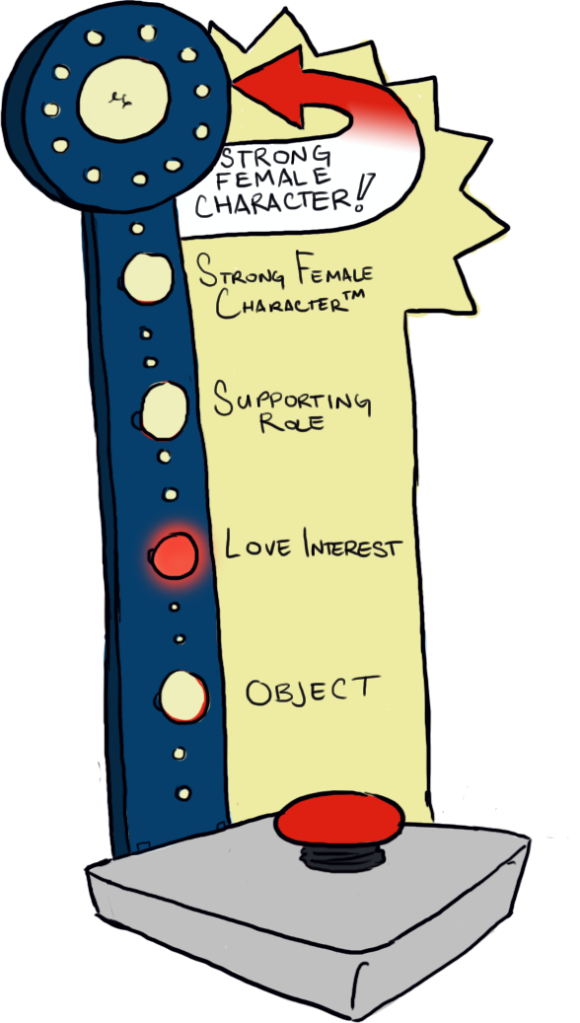

Verdict: Love Interest

Roxie Richter

Roxie Richter affects the story even before she is introduced. In the world of Scott Pilgrim,

male homosexuality has always existed, in the form of Wallace Wells,

his boyfriend, Mobile, the Other Scott, Kim’s roommate, Joseph, and, at

the last possible second, Stephen Stills. Queer female sexuality,

however, doesn’t warrant a mention until the fourth volume, when it is

suddenly EVERYWHERE. Kim and Knives have a drunken make-out session, and

Ramona starts to make comments about marrying Kim. Wallace tells Scott

to break out the “L” word, to which Scott responds, “Lesbian?” It seems

almost as if O’Malley thought he needed to remind his readers that women

can be interested in other women so we wouldn’t be shocked when an

actual queer woman showed up.

Roxie Richter affects the story even before she is introduced. In the world of Scott Pilgrim,

male homosexuality has always existed, in the form of Wallace Wells,

his boyfriend, Mobile, the Other Scott, Kim’s roommate, Joseph, and, at

the last possible second, Stephen Stills. Queer female sexuality,

however, doesn’t warrant a mention until the fourth volume, when it is

suddenly EVERYWHERE. Kim and Knives have a drunken make-out session, and

Ramona starts to make comments about marrying Kim. Wallace tells Scott

to break out the “L” word, to which Scott responds, “Lesbian?” It seems

almost as if O’Malley thought he needed to remind his readers that women

can be interested in other women so we wouldn’t be shocked when an

actual queer woman showed up.Roxie is introduced as an almost invisible force, which seems somehow appropriate when she represents a group of people heretofore invisible in the series’ universe. We learn that the canonical reason for this is that she is a half-ninja and therefore has a sword, as well as the ability to move with “almost ninja-like stealth and speed.” We also learn that Roxie and Ramona were roommates at the University of Carolina in the Sky, a floating school tethered to a mountain by a giant chain. Unlike any ex before her, Roxie seems to have Ramona’s number, calling her out on her habitual cheating. At the same time, Roxie is clearly the ex Ramona knows best, evidenced by the familiarity of their highly personal insults.

There is a strange and unpleasant subtext in the treatment and characterization of Roxie. She is intensely insecure, interpreting Ramona’s comment that she’s a lousy excuse for a ninja as a slight against her half-ninja status: “Half ain’t good enough, huh?!” When Knives’ father shows up to fight Scott, Roxie immediately assumes that Gideon sent him to help her. She has an emotional outburst, shouting, “I don’t need help! Why doesn’t anyone ever believe in me?!” Even the expository text doesn’t respect her, identifying her as the “4th evil ex-boyfriend.” Further supporting the idea that no one takes her seriously is the fact that, after Scott avoids every opportunity to fight her, one time even going so far as to hide in Ramona’s subspace suitcase, he defeats her with a single blow.

It seems to be no coincidence that she is the ex that represents a homosexual blip in Ramona’s largely heterosexual dating history. Her relationship with Ramona was, for Ramona, apparently just a phase. Even when Roxie promises to kill him, Scott doesn’t consider the possibility that she might be one of the evil exes or, indeed, the reason why Ramona no longer refers to them as her seven evil ex-boyfriends. Instead, he assumes that Roxie is merely dating one of the exes. The realization of her true identity is so momentous that it requires an entire page for Scott’s brain to literally crack open. He points a finger, almost in accusation, and then, when Ramona says that it was only a phase, he replies, “You had a sexy phase?!” Every other ex at this level is a serious threat, and Roxie is part of a sexy phase.

Indeed, the book even puts forward the idea that a woman cheating on a man with another woman isn’t actually cheating. When Ramona tries to apologize to Scott for Roxie staying at her place, she assures him that they “didn’t even make out that much.” This is apparently not infidelity enough to get in the way of an exchange of love confessions.

To add insult to injury, Roxie shows up in the volume where Scott finally gets up the nerve to tell Ramona that he loves her, thereby earning a sword representing the Power of Love. So the heterosexual man defeats the queer woman who dated his girlfriend with the power of heterosexual love. This may be the absolute worst statement made in the entirety of the series.

It’s especially obvious that Roxie and Ramona’s relationship is invalidated due to Roxie’s gender, as she is actually quite clearly second only to Gideon in the extent of her effect on Ramona. Ramona’s trademark rollerblades seem to be a riff on Roxie’s rollerskates. Roxie claims on two occasions to have taught Ramona everything she knows about subspace. She seems to be the only person Ramona didn’t just play with for a few days or weeks before she got tired of them, as demonstrated by their familiarity with each other and Ramona’s decisions to have lunch with Roxie and visit her gallery opening.

What complicates the portrayal of Roxie in the comic is, as always, the fact that we are still by the fourth volume quite firmly entrenched in Scott’s point of view. His heteronormative viewpoint may be affecting the storytelling itself. This seems unlikely, however, because most of the instances where Scott’s perspective has a profound effect are interrogated in some way. This is played pretty straight. (Pun intended.)

What is also played pretty straight is the film’s rendition of the Scott vs. Roxie battle. We’ve talked in every post in this series about the injustices done to the female characters in their translation from page to screen. In a lot of ways, it may have been more apt to call this series “Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World Vs. the Girls.” Still, no female character’s arc becomes more thoroughly offensive than Roxie’s.

Roxie, or Roxy, as she’s apparently called in the film, is introduced almost exactly as she is in the comic. Her defeat, however, could not be more different. This is partially because in the original, it’s not actually her battle, but rather one that takes place between Ramona and Envy. The battle begins when an invisible Roxy punches Scott in the back of the head and knocks him to the ground. As he sits up, we’re given a delightful view of him framed by Roxy’s legs, just to demolish any hope you may have had that Roxy was going to be treated as seriously as the other exes.

This becomes even clearer when Ramona tells Scott not only that her relationship with Roxy was a phase, but that “it meant nothing. I didn’t think it would count! … I was just a little bicurious.” As if this weren’t bad enough, the soundtrack for the reveal that Roxy is one of the evil exes is punctuated with breathy feminine sighs.

When Roxy then tries to attack Scott, Ramona intervenes; in this version, she doesn’t fight Roxy because Scott is hiding behind the rules of chivalry and his own terror, but because she just... does? It’s not explained. Roxy also suddenly fights with a whip-sword-belt-thing because, I don’t know, it’s sexier than a sword or something. (The change is likely a matter of increasing visual interest and avoiding repetition in a film where the final battle involves swords, but still...) When Roxy reveals that Scott will have to defeat her by his own hand, he protests, saying that he can’t hit a girl. Instead of denying Scott the moral high ground he thinks he deserves for taking this position, as Ramona and Roxie both do in the book, Ramona just tells him that he has no choice... and then proceeds to control his limbs as he enters into fisticuffs with Roxy.

Then something happens that makes us a little bi-furious. As Roxy lifts her leg in the air to deliver the final blow, Ramona tells Scott that Roxy’s weakness is an erogenous zone at the back of her knee. This will be familiar to readers of the comic as Envy’s weakness, discovered by Scott during a serious two-year relationship, and used to take her down in a non-lethal manner. In the movie, however, it is a weakness discovered during just-for-fun make-out sessions, used by a straight man to orgasm a queer woman to death. Roxy’s last words: “You’ll never be able to do this to her,” followed by a blissful moan. Our reaction: not suitable for print.

What really irks us about this scene is that it is so intentional. Roxy suffers a perfectly adequate, if still dubious, defeat in the comic, so the appropriation of Envy’s fight and weakness represents a deliberate change. A character that is already treated as a joke is humiliated in an incredibly offensive way, and we’re supposed to find it funny. We are, perhaps, even supposed to think it better than the original. We’re actually not sure what could have been worse.

Verdict: Love Interest (Comic) and NO NO NO OH GOD WHY (Film)

"he doesn’t fight Roxy because Scott is hiding behind the rules of chivalry and his own terror, but because she just... does?"

ReplyDeleteIt's because he doesn't want to hit a woman

And that fight also comes from somewhere else- look up the "Free Scott Pilgrim" comic where Scott goes against the Winifred Hailey clones. He can't hit a girl, so Ramona grabs him and makes him fight the clones.

Looks familiar?

--

In the film the bit about Roxy being angry when Ramona dismisses it as a phase *to Scott* reflects on Ramona negatively as a character; she trivialized what was supposed to be an important relationship

The reason why Envy was reduced in her role in the film - they didn't have the time (the film had five of six books and a tacked on ending in one), and I think I read somewhere that they wanted to wrap up the Envy stuff after the Todd Ingram fight

ReplyDelete