I

want to see more girl monsters. Girl giants, girl dragons, hulks &

trolls. Scylla and hydra. Girl monsters who are huge and whole. Teeth

and plush fur and long muscled tails. Heads enough to see you anywhere.

Gleaming green or brown. But girl monsters are usually zombies or

vampires. Pale and thin, bleeding or dead. Not Lady Lazarus, not a

phoenix from the ash. I want to see how you get strong without being

broken first. Get strong and stay strong. Get big and bigger.

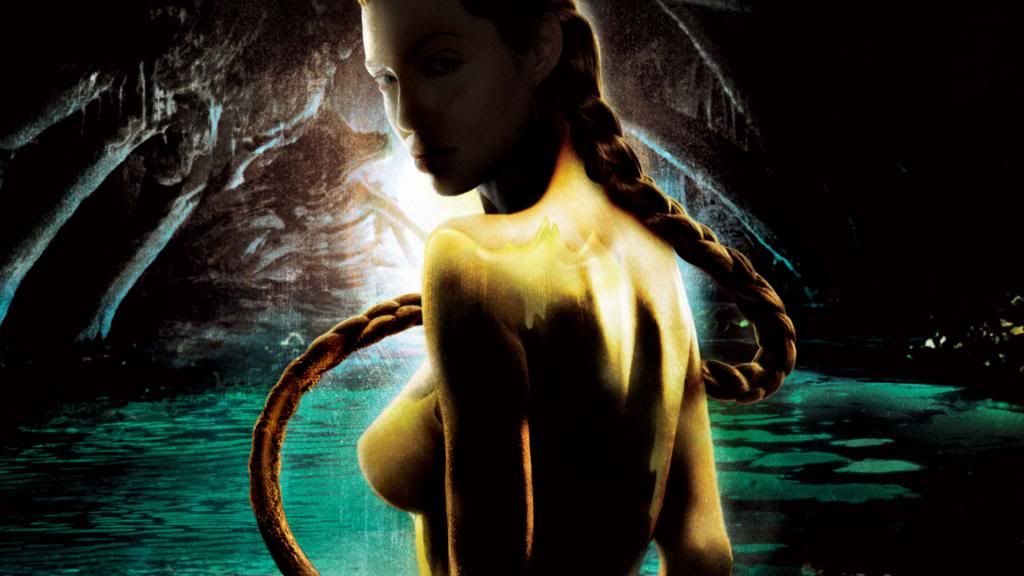

I once had a lengthy argument about just this issue. My male conversation partner argued in favour of our current standard of female villainy, suggesting that women must enact their evil through their seductive appeal. What makes these women terrifying is the control they exert over men using the innate power of their sexuality. The example he gave was Angelina Jolie as Grendel’s mother in Beowulf (2007). I suggested that such an approach was reductive nonsense.

I, like terror-incognita, am sick of seeing monstrous women as pretty, humanoid corpses or gorgeous succubi. Hollywood dictates that female monsters must be attractive, causing pleasure while wreaking destruction. We rarely get the opportunity to see truly monstrous women, because it seems that being sexy is more important than being terrifying. What I’d like to see is more female Grendels, mutilating and consuming dozens of people at a time before having their arms ripped off in a violent struggle. I’d also like to see these kinds of monsters embrace their rage without this rage being reduced to some supernatural example of that time-tested adage that “bitches be crazy.”

What really strikes me in terror-incognita’s observations, however, are those final lines: “I want to see how you get strong without being broken first. Get strong and stay strong. Get big and bigger.” We started this blog with a post that riffed on Joss Whedon’s responses to the question of why he writes strong female characters. Although we wanted to use the form of his speech, we also wanted to begin by acknowledging a writer whose work with female characters is contentious. In many cases, his writing is contentious for just this reason: many of Whedon’s women must be broken before they can become strong.

A basic Internet search should produce a number of critical analyses of this trope in Whedon’s work. I’m not interested in getting into the details of these issues in this post -- though rest assured, we will be doing a whole host of Whedonverse series -- but I will offer two examples. In Firefly and its accompanying materials, we learn that River Tam underwent extensive, traumatic experimentation in order to become the perfect assassin. In Dollhouse, Echo had her self removed in order to have it replaced by a whole host of plug and play personalities before she ultimately fashioned a complete self.

As another tumblr user, sorveharth, observes, “I think the main difference between a hero and a heroine in traditional narratives is that a hero’s strength is defined by how much he can win, while a heroine’s is defined by how much loss she can endure.” I don’t know about you, but I agree with sorveharth in saying that “that’s kinda fucked up.”

For further discussion of the problematic implications of women being broken in order to become strong, see also: Rape As Backstory and Sorry, But Rape Won’t Make Your Female Character More Interesting.