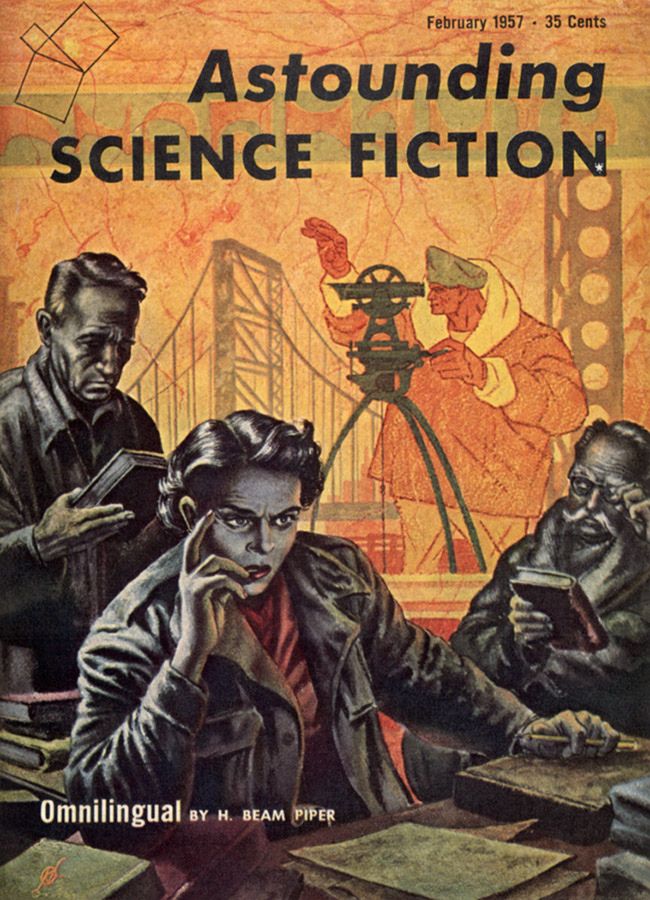

H. Beam Piper’s short story, Omnilingual, first appeared in the February 1957 issue of Astounding Science Fiction.

It focuses on Dr. Martha Dane, an archaeologist on a mission to Mars to

study the remnants of Martian civilization fifty thousand years after

its demise. A linguistic specialist, Martha makes it her goal to read

Martian, defying skeptical colleagues, the probability of the loss of

her reputation, and the fact that this could very well prove to be an

impossible task.

Martha

is, first and foremost, a consummate professional. She is

ultra-competent, creating almost single-handedly an entire system of

Martian pronunciation based on sounds that both humans and Martians

could make. She appreciates the work done by her helpers and doesn’t

allow herself to take the bait left by one of the other archaeologists, who is

trying to undermine her efforts. The senior archaeologist on the mission

hand-picked her, and he tells her that her standing is better than his

was at her age. This is no small compliment, considering his reputation

as a much lauded academic at the top of his field.

So

it’s a big deal when she decides to risk her own reputation on a

potentially career-ending wild goose chase. The main antagonist, Tony

Lattimer, constantly reminds her of that fact. He invites her along on

an exploratory mission, if she “can tear herself away from this

catalogue of systematized incomprehensibilities she’s making long enough

to do some real work.” He belittles the value of her efforts, trying to

bring the attention of the on-site reporters to physical artifacts of

the kind that attract his focus. Eventually, it turns out that his derision

came not from his confidence that Martha would fail, but his fear that

she would succeed and steal the limelight from him.

| |

| Kelly Freas |

The

two are pitted in opposition due to their conflicting goals: Tony wants

fame and recognition, while Martha seeks knowledge for knowledge’s

sake. One of their colleagues sums it up: “Tony wants to be a big shot.

When you want to be a big shot, you can’t bear the possibility of

anybody else being a bigger big shot, and whoever makes a start on

reading this language will be the biggest big shot archaeology ever

saw.” Martha, somewhat naively, asserts in the narration that she

doesn’t want to be a big shot; she just “wanted to be able to read the

Martian language, and find things out about the Martians.” She has no

interest in preserving or building her reputation; instead, she sets out

to take chances, make mistakes, and get messy. (Valerie Frizzle would

be proud.) Her work, while clearly more important than Tony’s -- even

his discovery of the desiccated bodies of a group of Martians -- doesn’t

have the same kind of viewer friendliness or immediate payoff; the

result is fewer workers assigned to her quest for knowledge and more

attached to his search for ratings.

Although

this conflict is not explicitly figured in terms of gender and power,

it’s hard to resist applying that lens. Tony makes himself the face of

the mission, recording voice-over for their broadcasts. He ensures that

he will be the one sent home to bring news of their accomplishments, as

seen from his perspective. He gets to shape the narrative as he sees

fit. Martha, meanwhile, does the heavy lifting with no thought of glory.

Even when she manages to start the translation process, she does so

with the help of a man’s knowledge, and she is only assured credit for

her work when two men step forward to defend her right to it. It’s a

subtle reminder of the story’s original postwar audience and the reality

of a social climate that persists to this day, in which women who make

monumental discoveries enjoy a smaller write-up in history or science

textbooks than their male counterparts.

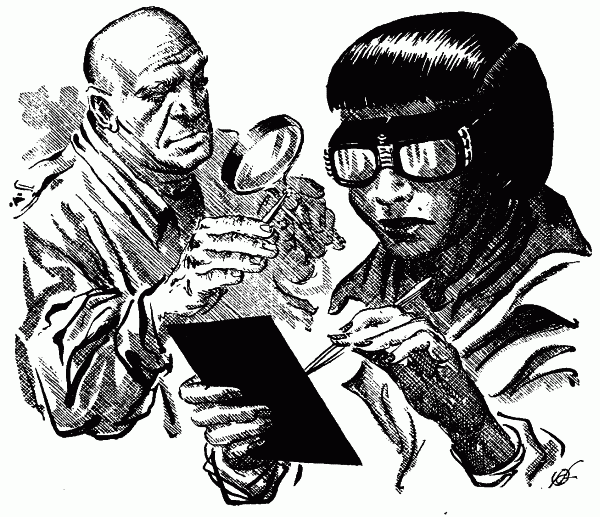

That

doesn’t mean that the story isn’t remarkably progressive. Not only is

Martha Dane an intellectual titan, she is an intellectual titan who

pulverizes the Bechdel test within five pages of existence. Her

co-worker, Sachiko Koremitsu, discusses her work with her and assists

her with it, often seeming to be the person most supportive of Martha’s

ambitions. Sachiko is, herself, a highly competent worker, restoring

books in such a way that “every movement was as graceful and precise as

though done to music after being rehearsed a hundred times.” One of the

other female characters, a professor of natural ecology at Penn State,

is the one who identifies their most important find as a university,

drawing from her own experience of working in one. Unlike, say, the most

recent Star Trek

film, the story features multiple women in different roles contributing

to a common goal. Also unlike that film, it allows them to speak to

each other about that goal.

|

| Kelly Freas |

Now,

before I make my ruling on this character, I want to acknowledge

something. Martha Dane is not the kind of character who inspires intense

fannish devotion, sending readers into paroxysms of delight at her

badass antics. In terms of science fiction heroes, she’s no Sarah Connor

or Ellen Ripley. In terms of archaeologists, she’s no Indiana Jones

(though she may have made Kingdom of the Crystal Skull more bearable). What she is is evidence that a protagonist can be a woman for no other reason than “just because”.

Could

this have been the story of a man who overcomes the opinions of his

colleagues to make the greatest discovery in archaeological history? Of

course. In fact, had that been the case, it would have been one of

several very similar narratives. Had it been written according to many

of our ostensibly modern sensibilities, it might have featured a

hackneyed plot focused on Martha’s guilt over choosing her career over a life

with a husband and children, giving us yet another reminder that women

can never “have it all.” Instead, it is the story of a woman who has no

children and no love interest, and the narrative never takes a moment to

mention either. Martha cares about her work, and the story cares about

her work, and, because of this, we care about her work. We don’t even

get the hinted-at distraction of a potentially haunted university and a

final third of the story spent learning Martian from ghostly

apparitions. What we have is the portrait of a woman, who is damn good

at her job, trying to get important stuff done despite the reservations

of her many critics, and succeeding... in space. She may not fight

robots or Nazis, but she is certainly an important character to know.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

No comments:

Post a Comment