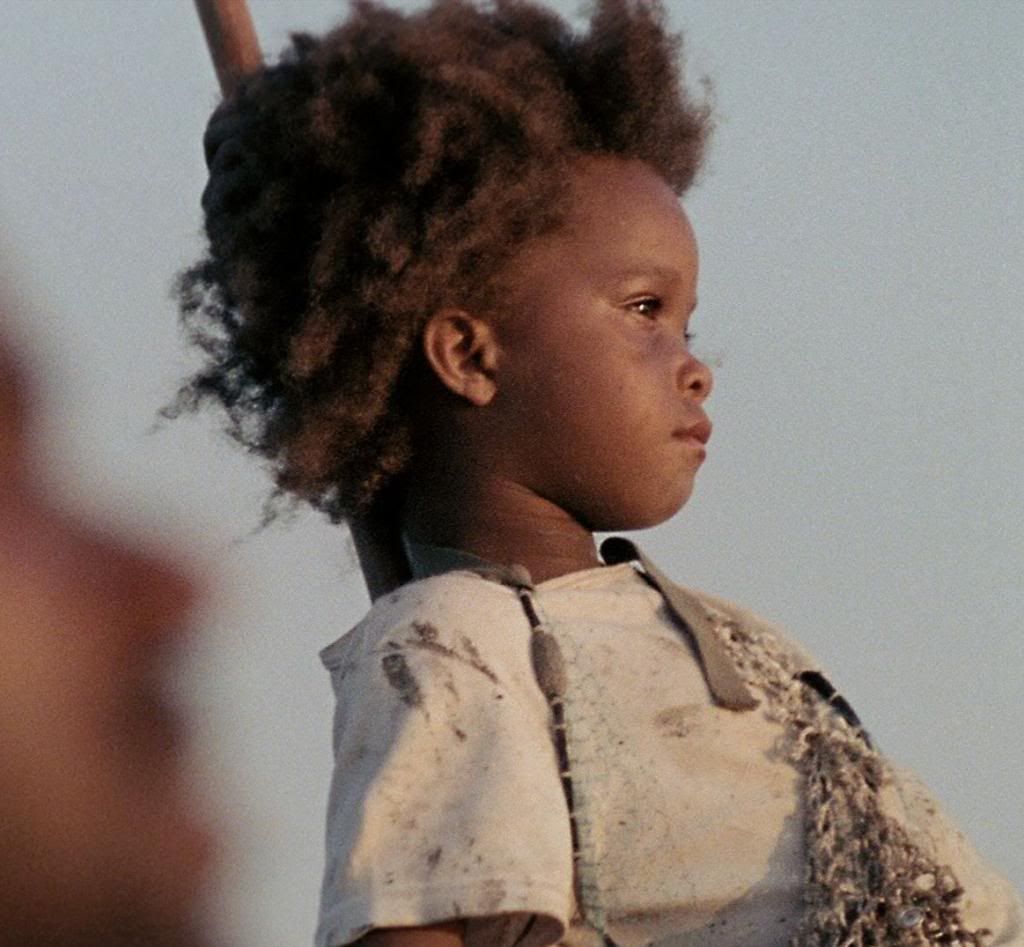

“When it all goes quiet behind my eyes, I see everything that made me, flying around in invisible pieces. When I look too hard, it goes away. And when it all goes quiet, I see they’re right here. I see that I’m a little piece of a big, big universe, and that makes things right. When I die, the scientists of the future? They’re gonna find it all. They’re gonna know: Once there was a Hushpuppy, and she lived with her daddy in the Bathtub.”Beasts of the Southern Wild begins at the end of the world. The people of the Bathtub, segregated from society by an extensive levee, have adopted a lifestyle that emphasizes survival above all else. The Bathtub is an atypical riff on the pop cultural image of a post-apocalyptic landscape, a community where children eat their fill of whole chickens before tossing the carcass to the animals, fathers build boats out of truck beds, and everyone waits for a flood that will destroy their very way of life. It’s a portrait of a community that has learned to become self-reliant, facing the ultimate test of their ability to survive.

It is also the portrait of Hushpuppy, a very young girl who exemplifies the group’s irrepressible spirit. There are some things that we should establish about Hushpuppy right off the bat. Although she does live with her father, she technically lives in a separate building. As a six-year-old living in her own house, Hushpuppy must often fend for herself, and this includes preparing meals. In one memorable scene, faced with the need to heat her food, she turns on the gas, dons a football helmet, and lights the element with a flamethrower. Task complete, she returns her tools to the freezer.

What I’m establishing, of course, is that Hushpuppy is a badass. This isn’t what sets her apart from other characters, however; many films are filled to bursting with characters intent on showing us just how awesome they are. What makes Hushpuppy stand out is the fact that her awesomeness is so effortless and practical. She needs a fire, so she makes one. Later in the film, she needs to swim across a vast expanse of water, so she does. Her badassery is just a matter of fact.

Still,

such sincere excellence deserves to be deconstructed, and I think it’s

only right that we allow Hushpuppy’s own words to be our guide. To that

end, we begin by discussing “everything that made her” and, more

specifically, the influence of her parents.

Still,

such sincere excellence deserves to be deconstructed, and I think it’s

only right that we allow Hushpuppy’s own words to be our guide. To that

end, we begin by discussing “everything that made her” and, more

specifically, the influence of her parents.For the majority of the film, Hushpuppy’s mother is a conspicuous absence. Hushpuppy tells us that her mother “swam away,” and that she keeps everything her mother left behind in her house. She makes herself into a caretaker of her mother’s memory, hanging her basketball jersey on the wall beneath a drawing of her smiling face. When Hushpuppy burns her house down, her mother’s jersey is the only thing she saves. When the floods come, she keeps it safe in her grasp. Clinging to her jersey represents Hushpuppy’s only acknowledgement of her own need for comfort in the face of her father’s short temper and difficult moods. Faced with her father’s impending death, she seeks out her mother; in the flesh, the woman can only offer temporary comfort, as Hushpuppy seems to realize that hiding in her mother’s arms won’t solve anything.

In this tale, Mama is the chief magical presence and it may be because of this that she can’t stay. She is so beautiful that the stove lights itself in her presence and so fearless that she takes on alligators in her underwear, armed with a shotgun. Hushpuppy’s encounter with the woman who might be her mother echoes the meeting between an ancient Greek hero and his divine father, allowing her to acknowledge her roots and decide, at the same time, that Mount Olympus is not the place for her. The fact that the club where her mother works is called “Elysian Fields” only strengthens this mythological connection. It also suggests an alternative reading: that Hushpuppy crosses the River Styx and visits her mother in the Underworld, only to return to her father when it is his time to cross over. In place of a pomegranate, she offers fried alligator; instead of Charon’s ferry, he travels in his own truck bed boat.

The end of the world narrative that consumes Hushpuppy’s imagination has its roots not only in the global warming-induced flooding of her home, but in her father’s illness. Hushpuppy’s father, Wink, is the most important figure in her life; when she discusses the realities of existence, it is almost always in the context of what her daddy says. Because he has played an integral part in establishing her conceptualization of reality, she comes to believe that his death will be her own end. She only accepts that she can live beyond her father when he assures her of the fact.

This doesn’t mean that Hushpuppy is in any way passive or weak; it’s just a reminder that she is a six-year-old kid, and at that age “everything that made you” is still working on it. It also doesn’t mean that she never defies her father or rejects his version of events. Indeed, many of her defining moments occur in scenes where she does just that.

After Wink leaves Hushpuppy alone for a matter of days to go to the hospital, she burns down her house to get his attention. He chases her down and demands that she approach him to receive her punishment. When she refuses, he hits her and tells her that looking after her is killing him. Her response? A verbal lashing -- “I hope you die. And after you die, I’ll go to your grave and eat birthday cake all by myself” -- and a punch delivered right to her father’s heart. He falls to the ground, and his pained convulsions are interspliced with shots of melting ice caps, linking Hushpuppy’s violent actions to the coming apocalypse. This link is solidified -- at least in Hushpuppy’s mind -- when she finds the population of the Bathtub in full evacuation mode following the announcement that the storm is coming. She observes in her voice-over, “Mama, I think I broke something.”

So begins Hushpuppy’s quest to save the universe. Convinced that the universe is comprised of carefully arranged pieces and that “if one piece busts, even the smallest piece, the entire universe will get busted,” she seeks some way to undo the damage for which she feels responsible. To this end, she blows a hole in the levee and releases the flood waters, pulling the plug from the Bathtub. At the same time, she learns that there are some things that cannot be remedied, and her father’s illness is one of them. We’ve spoken before about narratives like Brave, in which the protagonist makes a mistake and must then correct it. What makes Beasts of the Southern Wild particularly fascinating is that it appears to be just this kind of film; in this mythical environment, the daughter of a magical woman should be able to fix her mistakes. However, that is not the case. Instead, Hushpuppy must learn to accept that there are things she can’t change, even as she is also discovering the extent of her ability to affect the world around her.

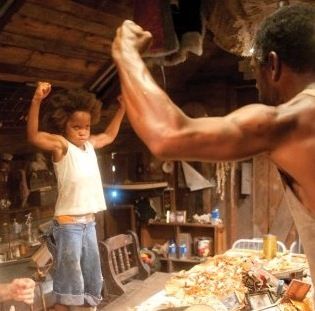

While learning when to accept your powerlessness may be a fascinating -- and often ignored -- lesson, what is more compelling is Hushpuppy’s journey to self-reliance. Faced with his own mortality, Wink makes it his job to teach Hushpuppy how to survive without him. He shows her how to fend for herself in practical ways, at one point teaching her how to catch fish with her bare hands. More importantly, though, he instills in her a tremendous sense of self-worth and faith in her own abilities. He refers to her throughout the film by the nickname “Boss Lady,” verbally placing her in a position of power. When he sees someone else teaching her how to pry apart a crab with a knife, he turns the task into a test of her survival ability. He tells her to “beast” it, to tear it apart and break the dorsal shell with her bare hands. What’s more, he turns it into a rite of passage, recruiting the rest of the remaining Bathtub inhabitants to chant along with him. When Hushpuppy manages to break the shell, taking to the table to flex her muscles and give a primal scream, she has earned her moment of glory.

This typically masculine display fits into Wink’s larger project of making Hushpuppy into the king of the Bathtub. In a way, this highly public feat becomes Hushpuppy’s introduction to her subjects, a demonstration of her suitability to lead them. However, this is complicated by the fact that many of Hushpuppy’s accomplishments, by virtue of being part of this kingship narrative, are cast in terms of a triumph of masculinity. The most telling example of this occurs after Hushpuppy tries to confront her father about his illness and her own mortality. In order to force his way past a moment of emotional vulnerability, Wink challenges his daughter to an arm wrestling match. She wins, and responds to his question of who’s the man with “I’m the man! I’m the man!” Again, in a moment of triumph, she asserts her masculinity.

It’s a troubling aspect of the film, if only for the fact that it reminds us that a female character’s strength is often measured in terms of how well she adheres to traditional standards of masculinity. To my mind, what makes the film’s treatment of this issue slightly less problematic is the presence of two women who espouse a similar self-reliance. While Wink figures his survival lessons as, basically, passing on the lessons of manhood, both Miss Bathsheba and the Cook (who might be Hushpuppy’s mother) emphasize the necessity of being able to take care of yourself. However, Miss Bathsheba expands this definition of survival to include looking out for people who are weaker than you, building on Wink’s more selfish approach. The Cook, who serves as Hushpuppy’s third model of behaviour, brings these two ideas together by verbally instructing Hushpuppy to be responsible for her own life and, if she is the girl’s mother, physically protecting Wink from the alligator. In neither case is she seen as anything but feminine.

One of the themes of the film is finding your place in the world. While figuring out how to negotiate the dicey waters of socially constructed gender roles is part of that, the film focuses on a different aspect of relating to the universe. The first time we meet Hushpuppy, she holds a bird up to her ear and listens to its heartbeat. She then goes around to all the animals on her property doing the same thing, accompanied by her own voice-over: “All the time, everywhere, everything’s heart’s are beating and squirting and talking to each other the ways I can’t understand. Most of the time, they probably be saying, ‘I’m hungry,’ ‘I gotta poop,’ but sometimes they be talking in codes.” While she feels cut off from the meaning of these messages, she doesn’t stop trying to translate them. She even seems to have some success, discovering the source of her father’s illness in his heart.

Her most impressive act of translation, however, is the one she performs with the aurochs. When the aurochs are first introduced, it is as predators who would make the deliciously named Hushpuppy their lunch. Over the course of the story, however, she comes to identify with them, evidenced by the connection she forges between the aurochs and her family members through the linguistic link of their description as “animals.” In the climactic scene, as the other girls run to get away from the aurochs, Hushpuppy’s steps remain measured and determined. She turns to face them and they bow before her. She acknowledges their offered truce, stating, “You’re my friend, kind of.” It is an incredibly powerful image: a six-year-old girl standing, unflinching, before a prehistoric giant as they come to a mutual understanding of one another.

Benh Zeitlin, the director and co-writer of Beasts of the Southern Wild, sums up the scene quite nicely:

“What interested me is that you have these two animals on the verge of extinction that are designed by nature—one is supposed to eat the other, and the other one is supposed to kill its predator in order to stay alive. But both creatures are these wise, honorable animals that understand at the end of the film that the greatest sin you can commit is to kill an animal on the verge of extinction—to kill the last of a kind. So it’s not just about your own survival. It’s about allowing each other to go on.”Unlike a typical fairy tale narrative, in which the prince or knight slays the monster in order to prove his worth, the film allows both king and beast, prey and predator, to go on, finding its message in the continuance of life instead of its end.

This message finds its most potent expression in Hushpuppy’s self-narrativization, as she makes a point of ensuring her own immortality. She takes to painting images of her life on beds, floors, and cardboard boxes, echoing the early humans who drew aurochs on their cave walls. In this way, too, she resembles the creatures that emerged from the ice, though her survival will be less literal than theirs. By telling her own story, she seeks to make a place for herself, her father, and the people of the Bathtub in the historical record.

There is something truly epic about her assertion that people will know her name hundreds or thousands of years into the future. She is precisely the kind of person that history forgets: an impoverished Black girl living on the margins of society. Still, she speaks directly to us, expresses her experiences in art, and has faith that she will play an important role in the story of civilization. That’s plenty of reason to remember her.

Verdict: Actual strong female character

This is amazing and beautiful and I'm so glad you wrote it and I really need to see this film again. *flops about*

ReplyDeleteThis is amazing and super helpful for my film study at school, thank you :)

ReplyDeleteThis a great article

ReplyDelete