“My mommy always said there were no monsters -- no real ones -- but there are.” When Newt speaks those words in Aliens, she is a young girl who has been confronted with horrors the likes of which euphemisms can’t describe. When Ripley speaks the same words in Alien: Resurrection, it is as an alien-human hybrid, forced to confront the monstrosity in both her creators and herself. In the latter case, I’m inclined to believe that Ripley is also talking about the film itself.

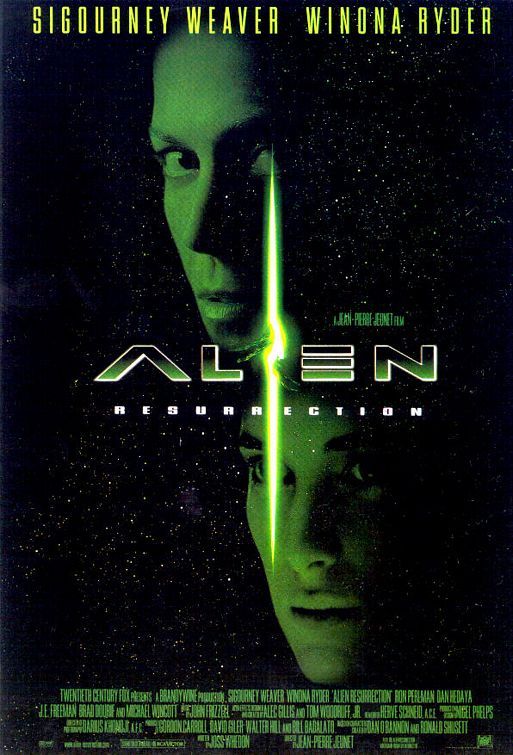

If Alien: Resurrection took corporeal form, it would be the kind of creature you wouldn’t want to find lurking in your bed or hiding in your closet. Just ask its screenwriter, Joss Whedon; it’s been hovering over him for years. Back in 2005, eight years after the film’s release, Whedon claimed that the script became a monstrosity only after it left his hands:

“It wasn’t a question of doing everything differently, though they changed the ending, it was mostly a matter of doing everything wrong. They said the lines... mostly... but they said them all wrong. And they cast it wrong. And they designed it wrong. And they scored it wrong. They did everything wrong that they could possibly do. ...It wasn’t so much that they’d changed the script; it’s that they just executed it in such a ghastly fashion as to render it almost unwatchable.”

As recently as April of this year, Whedon is still answering for the film that, if it were a person, would be old enough to get a driver’s license:

“When you are making a movie you are making something that is going to last forever, especially now with the internet. So there is always going to be a shitty Alien movie out there. A shitty Alien movie with my name on it.”

Alien: Resurrection displays Frankenstein’s monster levels of doggedness in pursuing its creator.

And so it should, because it is a mess. The film begins with Ripley speaking those loaded words as we see her body floating in a tube, growing from child to adult. It turns out that she is on the USM Auriga, a medical research vessel where a group of ethically challenged scientists have been attempting to clone Ellen Ripley, in order to replicate the alien queen she died to destroy. They find success on their eighth attempt, and they decide to let Ripley 8 live, conducting a series of tests which show not only that she is a fully-functioning adult, but that she has retained some of the original Ripley’s memories. This turns out to be helpful when the aliens predictably turn against the scientists who sought to tame them, and the time comes for Ripley to take out the aliens for good (for the third time).

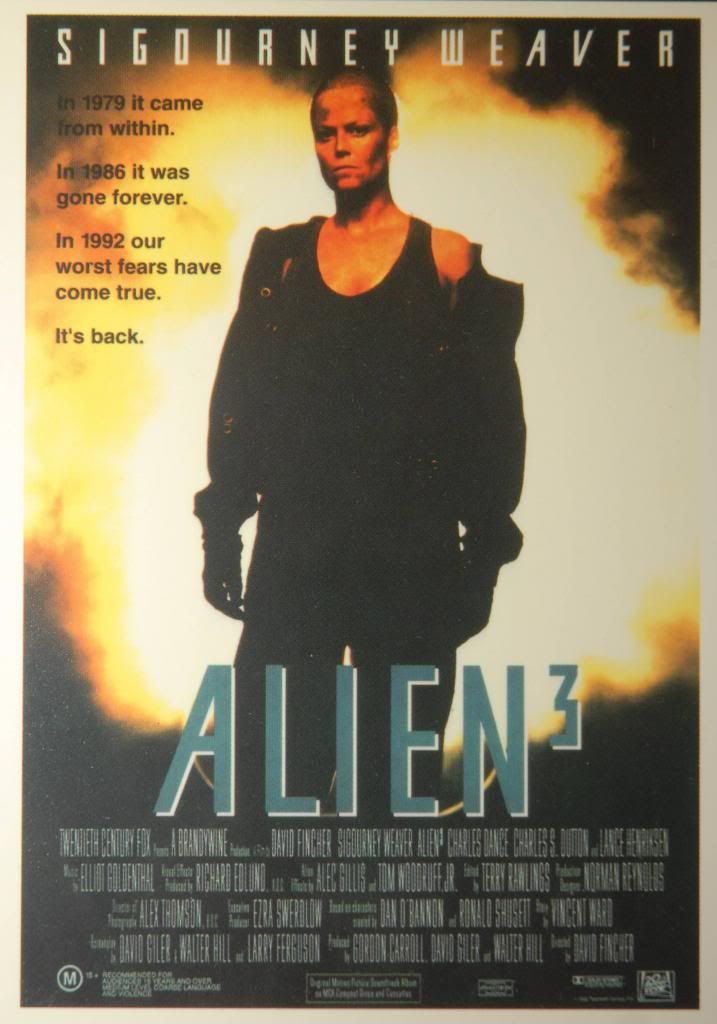

The first thing to get out of the way in this analysis is the fact that Ripley 8 is not Ellen Ripley, and I will admit that I consider this one of the great flaws of the film. The original Ripley survived almost entirely thanks to her wits, so it is difficult to see her become one in a long line of Whedon’s dark-haired, damaged, ass-kicking superwomen in a box (or tank, as is the case here). Ripley established herself as a hero without the benefit of powers, but the creative team behind this film clearly thought that that wasn’t cool enough. Instead of allowing her to remain a shining example of unaltered humanity, they beefed up her power set. The new and ostensibly improved Ripley has super strength, acid blood, a lightning quick healing factor, and a “highly evolved instinct,” all of which she acquired as a result of the cloning process combining her DNA with that of the alien queen.

Now, I love superheroes as much as -- and probably more than -- the next person, but many of my favourite heroes are the Badass Normals. There is something incredibly appealing about a person who struggles to save the world without the security of invulnerability or superspeed, about a fragile human who risks their life to save people like them, not because great power demands great responsibility, but because the right thing to do is the right thing to do. This is the appeal of Ellen Ripley, a woman who was third in command on a mining ship, but nevertheless stood up to the military, the uncaring capitalist machine, a group of dangerous criminals, and an alien threat that could eradicate human life. Giving her superpowers makes it seem like she needs superpowers, and anyone who’s seen the first two films knows that isn’t true.

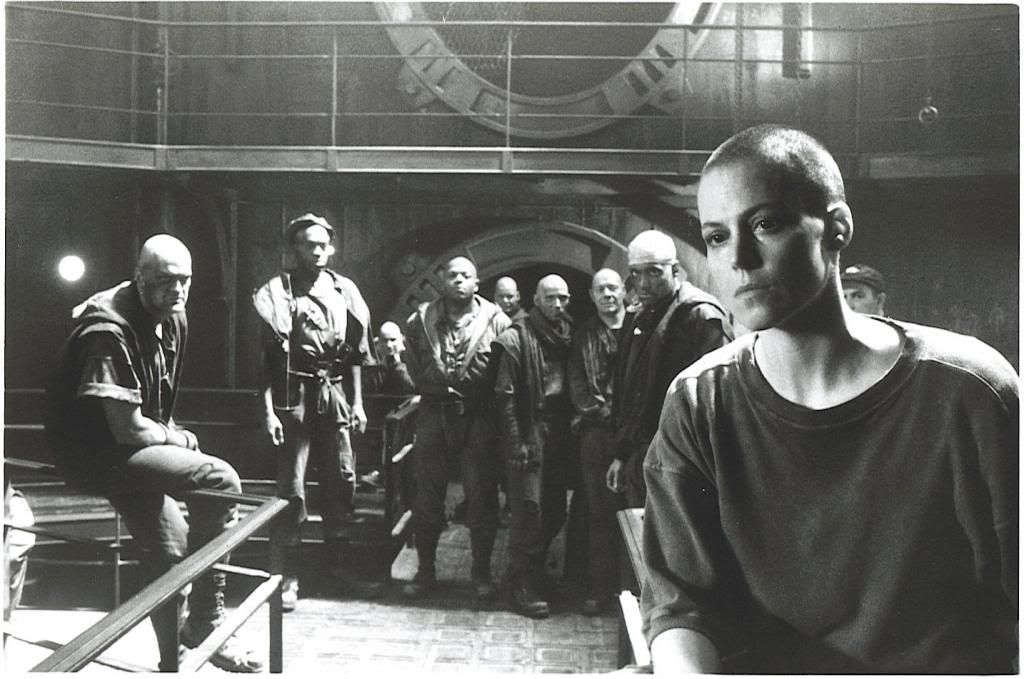

The objectification that forms an important part of the cloning plot further complicates the film’s treatment of new Ripley. We first see Ripley 8 as naked, slumbering specimen, surrounded by four scientists who are observing her. She is an object of scientific study, referred to by one of the major scientists as “it” as he coolly explains her memory loss -- likely incurred as a result of her traumatic situation as “connective difficulties caused by a biochemical imbalance causing emotional autism.” General Perez talks about “putting her down” and calls her a “meat by-product” of their quest to remake the queen. Even Annalee Call, who comes to respect Ripley, initially tells her, “You’re a thing, a construct. They grew you in a fucking lab!” Admittedly, this is a bit rich coming from Call, who is herself revealed to be an android designed by androids: a thing made by other things.

As the film progresses, the question of Ripley’s nature becomes less a matter of thing versus person than of alien versus human. A pivotal moment occurs when Ripley 8 is confronted with a room full of failed clones, all of which are horrific combinations of human and Xenomorph physiognomy. Ripley 8 is appalled by the collection, and responds to the seventh clone’s request for death by burning down everything in the room. Immediately afterwards, she threatens one of the scientists with her flamethrower, turning her anger on the representative of the people who created her. Call talks her down, denying her the opportunity to punish those responsible for the Ripleys’ suffering. After this scene, which ends with a particularly awful moment in which a man dismisses her actions as a waste of ammo caused by “a chick thing,” Ripley has ample reason to hate the humans.

Despite this, she retains some recollection of the original Ripley’s devotion to humanity, and she tries to understand it. In order to do this, she turns to another somewhat human person, Call, and asks her why she cares what happens to the humans. Call tells her that she is programmed to do so, and Ripley replies, “You’re programmed to be an asshole?” It’s a strange connection to make; how does caring about people make someone an asshole? Is this an attempt to show the difference between Ripley 8 and the original, who cared deeply about people as individuals and as a group? It may be, but it could also tell us that Ripley 8 is finding it difficult to cope with the failure that seemed to accompany her original’s every success. Ripley explains that she once understood how it felt not to be able to let humans destroy themselves: “I tried to save... people. It didn’t work out. There was this girl. She had bad dreams. I tried to help her. She died. Now I can’t even remember her name.” She tells Call about the effects of her original’s experiences: “When I sleep, I dream about them. It. Every night. All around me, in me. I used to be afraid to dream, but not anymore. … Because no matter how bad the dreams get, when I wake up it’s always worse.” Caring about people doesn’t necessarily make someone an asshole, but the miserable existence that Ripley 8 associates with caring about people might.

Unfortunately, her life doesn’t get much better following this discussion. Just when we learn that she is still trying to cope with the death of her adopted daughter, the alien queen she sort of gave birth to demands her attention. Ripley is called into the aliens’ nest, where the queen is giving birth, thanks to a human reproductive system she developed as a result of the hybridization that occurred during the cloning process. From her womb emerges the Newborn, a more fully realized alien-human hybrid, who immediately kills her and adopts Ripley as its new mother. It clearly feels betrayed when Ripley nevertheless causes it to be sucked out, piece by piece, into the vacuum of space.

I initially intended to analyze these final scenes as a continuation of the series’ treatment of motherhood, but nothing in these scenes really tells us anything new about Ripley, except, perhaps, that this version of her is willing to choose the human race over a creature that isn’t really her child. Sure, she’s genuinely sorrowful and apologetic, but she’s still getting rid of the alien threat, securing the cradle of human civilization just before the Xenomorphs can reach it.

Except she doesn’t actually save Earth, because there’s no Earth left to save. Technically, the planet still exists, but the people she spent four movies protecting are already gone. Earth appears to have been abandoned for decades.

Throughout the series, Ripley has two goals: destroy the Xenomorphs and go home to Earth. In Alien: Resurrection, she finally achieves both of these goals, but what should be a happy ending is ultimately a betrayal of the series. Ripley wanted to eradicate the aliens in order to prevent them from getting back to Earth and wiping out humanity; though she suffered tremendously, she knew it was worth it to keep people safe. However, when she arrives on Earth, it seems that humans have done a fine job of destroying it all on their own. Despite her efforts, the planet she gave her life to protect is still in shambles. Strengthening the blow is Ripley’s final line: “I’m a stranger here myself.” By having Ripley remind us that, as a clone, she has never actually stepped foot on Earth, the film cheapens its hero’s triumphant return. She does not go home; instead, she emerges into a new kind of strange alien landscape. She doesn’t lose, but she certainly doesn’t win.

In the interest of staying on topic, I’ve left out many of the the truly monstrous aspects of Alien: Resurrection: its often hammy acting, its awkward dialogue, and its parodic disregard for earlier instalments in the series, including the random replacement of MU-TH-UR with FA-TH-UR and the announcement that the omnipotent corporation, Weyland-Yutani, had been bought out by Walmart. It is a confused movie, a parody of the Alien films that nevertheless sees itself as the final part of the series, like a terrible version of Galaxy Quest whose creators intended it to be a proper Star Trek sequel. It’s the kind of monster you’d consider keeping under your bed, if only to keep it away from your television screen.

Verdict: Strong Female Character™. I’m not giving full credit to a version of Ripley that the original character would detest.