I’ve

had this post open for two days now, staring at a flashing cursor on a

blank page. This seems strange, because when I first saw the request for

an analysis of Diablo Cody and Jason Reitman’s Oscar-winning film, I

immediately wanted to get cracking. And then I re-watched the film.

It’s

not that this film is poorly made or unenjoyable; quite the contrary.

The problem is one of interpretation, and that process, as applied to

the story of a pregnant teenage girl, has only become thornier with the

recent legislative attacks on women’s reproductive agency. Both sides of

the debate could easily claim victories in Juno’s

success. The pro-life contingent can point to the fact that Juno

decides to carry her pregnancy to term, explicitly turning down the more

convenient solution of abortion, while the pro-choice side can refer to

the numerous indications throughout the film that everything about this

pregnancy, from having unprotected sex to choosing to give her child

away to an adoptive family, is solely Juno’s choice. Those seeking an

apolitical reading might consider it the story of one young woman’s

individual experience with pregnancy. Essentially, what we’re facing is

the need to discuss both Juno the character and Juno the film.

We

begin with the former. When we first meet Juno MacGuff, she is guzzling

Sunny D and trading verbal barbs with a particularly articulate

convenience store clerk. Juno is something of a word wizard, and much of

her characterization comes through her dialogical stylings; she is

intelligent, witty, and amply endowed with a quirky, sometimes poetic

sensibility. This speaking style strikes some who watch the film as

overtly false; a number of people in one of my screenwriting classes

blamed their inability to connect to Juno as a character on her

seemingly artificial speech. While I concede that it can be frustrating,

I would argue that Juno’s verbal self-expression is supposed to be a

bit alienating. Take, for example, the conversation in which she tells

Paulie Bleeker that she’s pregnant with his child. She explains that

she’s planning to have an abortion: “I was thinking I’d just nip it in

the bud before it gets worse, because they were talking about in health

class how pregnancy, it can often lead to... an infant.” She sounds

detached, but we can see that she isn’t. If you look past the wall of

false bravado and carefully constructed carelessness, you see a

terrified girl trying to make the best of a bad situation.

We’ve

spoken at length about titles and what it means when women are excluded

from them. In this case, the fact that the title is the female

protagonist’s name speaks volumes about her importance. This is truly

Juno’s story, and that is made clear in several ways. The first is both

the most obvious and the most important: the world of the film revolves

around Juno. She is, as she observes at one point, a planet, and the

other characters are moons in orbit. This may not seem like a big deal,

but there is something to be said for a film in which the female lead

gets the screentime, the narrative focus, and the witty commentary. It

tells us that her story matters.

It

also tells us that we should pay attention to her as something more

than a teen pregnancy statistic. Juno is fiercely unique and, at first

glance, this comes across as something like the super special snowflake

aspect of the traditional Mary Sue. In an early scene, the camera

lingers on the eccentric decor of Juno’s room, as if to confirm that she

really is just as quirky as we think. A little later, she waxes

philosophical about the desire of teenage boys for girls like her:

“freaky girls: girls with horn-rimmed glasses and vegan footwear and

goth make-up, girls who, like, play the cello and read McSweeney’s

and want to be children’s librarians when they grow up.” She even goes

so far as to contrast herself with the “perfect cheerleader” type.

At

the same time, Juno seems to be a subversion of this very trope. She

genuinely loves and appreciates the eclectic, speaking intelligently

about classic rock and taking a keen interest in both truly terrible

zombie films and a manga about a pregnant superhero. She doesn’t scorn

the popular cheerleader types; in fact, her best friend, Leah, is one of

their number, and she clearly has a great relationship with her.

Finally, during her description of freaky girls, we see a girl on a

black background, arranged like a paper doll. The transformation of this

doll-girl into a “freaky girl” occurs as though some unseen person were

dressing her in an assortment of tabbed outfits. It suggests that Juno

recognizes the performative nature of the public personas that we

project in high school, as well as their inherent superficiality.

Perhaps this is why she seems so set on not caring what other people

think.

What

I find fascinating about Juno is the way in which she is allowed to be

flawed. She’s the kind of character who recounts tales of a girl making

drug-addled claims of krakenhood, and it turns out that she was the

aspiring sea monster in question. When she tells her parents about her

pregnancy, they legitimately consider expulsion, vehicular assault, and

legal trouble more likely topics for a Juno-focused family meeting.

Despite her obvious intelligence, she doesn’t put any effort into her

schoolwork, copying from Bleeker and wryly observing that her

contribution to their science partnership is “charisma.” She has no

sense of proper etiquette, and she doesn’t respect the boundaries that

separate her life from the lives of the couple to whom she is planning

to give her child. The catalyst of the film is her decision to have

unprotected sex and, while several characters point out just how foolish

this decision was, they still make a point of helping her with the

consequences.

Juno

herself finds something positive in a difficult situation. Having been

abandoned by her own mother, who left to start a new family and whose

only acknowledgement of her first-born is the gift of a cactus every

Valentine’s Day, Juno seeks a secure, loving home for her baby. When

Mark tells her that he is planning to leave Vanessa, she reveals her

hopes for her child: “I want things to be perfect. I don’t want them to

be shitty and broken like everyone else’s family.” Part of her desire

for a perfect life for the baby seems to come from her need to live

through him vicariously. She gets to talk rock music and zombies with

Mark for a few months, but her kid would get that for a lifetime. Even

her decision to give the baby to Vanessa could be seen as a way to give

her child the mother she didn’t have and couldn’t be. Despite her

apparent cynicism, Juno is idealistic.

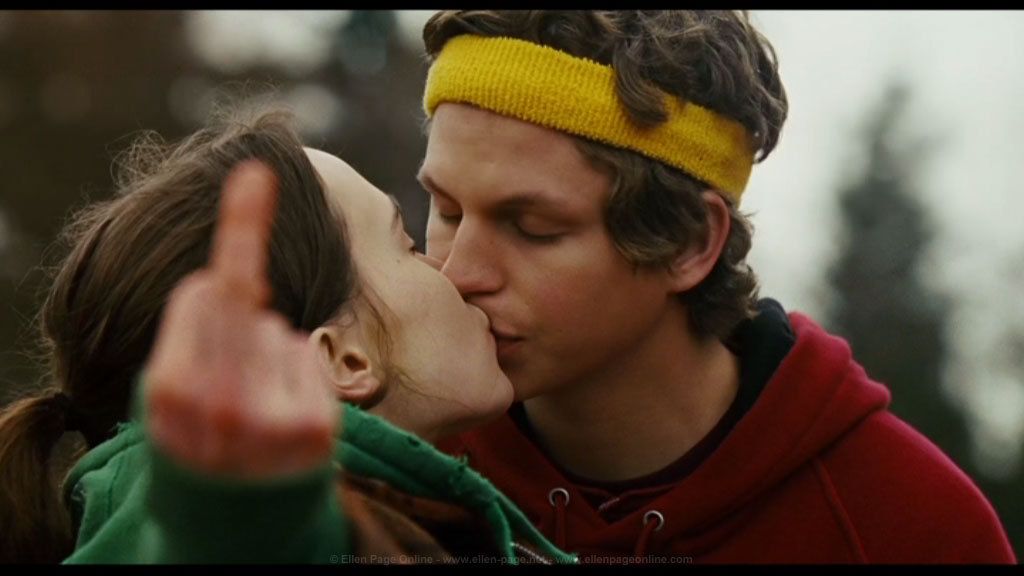

Her

idealism extends into the realm of romance. Over the course of the

film, she comes to realize that she is in love with Bleeker, but she is

also confronted with the harsh reality that love rarely conquers all.

When she asks her father to reassure her, he offers the following

advice: “Look, in my opinion, the best thing you can do is find a person

who loves you for exactly what you are. Good mood, bad mood, ugly,

pretty, handsome, what have you: the right person’s still going to think

the sun shines out your ass. That’s the kind of person that’s worth

staying with.” It’s a solid message, and it leads to a happy ending.

It’s this happy ending that brings us back to Juno

the film and the question of its political message. On the pro-choice

side, we have the undeniable fact of Juno’s agency. She chooses to have

sex; she chooses to get an abortion, then chooses not to; she chooses to

find an adoptive family for her baby, and she chooses to give him to

Vanessa even after the fantasy life she imagined for him falls apart.

When Juno tells Paulie that she’s pregnant and tells him she’s planning

to abort, he is supportive of her choice and tells her to “do whatever

you think you should do.” He understands that, ultimately, it is her

decision. Further supporting a reading of the film as pro-choice is the

sheer number of casual references to abortion. It’s not stigmatized in

the least, and both Juno’s stepmother and her best friend suggest it as

an option. Leah even mentions that she called a clinic for one of their

classmates the year before, treating it as a normal medical procedure.

Then, of course, there’s the ridicule heaped upon the pro-life movement

in the form of Su-Chin and the infamous “All babies want to get borned”

protest outside the clinic.

On

the other hand, the clinic itself is hardly a rousing endorsement for

the cause. The receptionist is blasé about bomb threats, dismissing the

very real incidents of anti-abortion violence. She urges Juno to take a

flavoured condom because it “makes [her boyfriend’s] junk smell like

pie.” Instead of merely reminding Juno to fill out her information

thoroughly, she tells her to give all the “hairy details” about “every

score and every sore.” In her own way, she’s as ridiculous as Su-Chin.

The more obvious argument in favour of the pro-life side is the happy

ending that results from Juno’s decision to give birth. At the end of

the film, Juno and Bleeker are blissfully happy together, Vanessa has

exactly what she wanted, and Juno’s stepmother has the dogs she adores

(because Juno magically overcame her allergy, I guess). Everyone’s lives

have improved, and Juno’s plan to consider the pregnancy a nine-month

blip in her life has apparently been successful. I don’t want to claim

that this could never happen, but it does seem awfully convenient.

Honestly, I’m inclined to believe that Juno

is intended to be an apolitical film, and I understand that a film that

takes its structure from the length of a full-term pregnancy would be

pretty short if said pregnancy was terminated in the first couple of

months. However, in a media climate where just about every woman chooses

to carry the fetus to term (see recent, ridiculous examples in American Horror Story and The Walking Dead),

I don’t think it’s too much to ask for one show to do more than pay lip

service to the idea of abortion. You can try to normalize it through

repeated references to its availability, but if no character ever takes

advantage of it, even in cases when it’s the only sensible option, it

will remain stigmatized. While I’m happy that the Junos exist, I could do with a few more Maudes.

Verdict: Actual strong female character